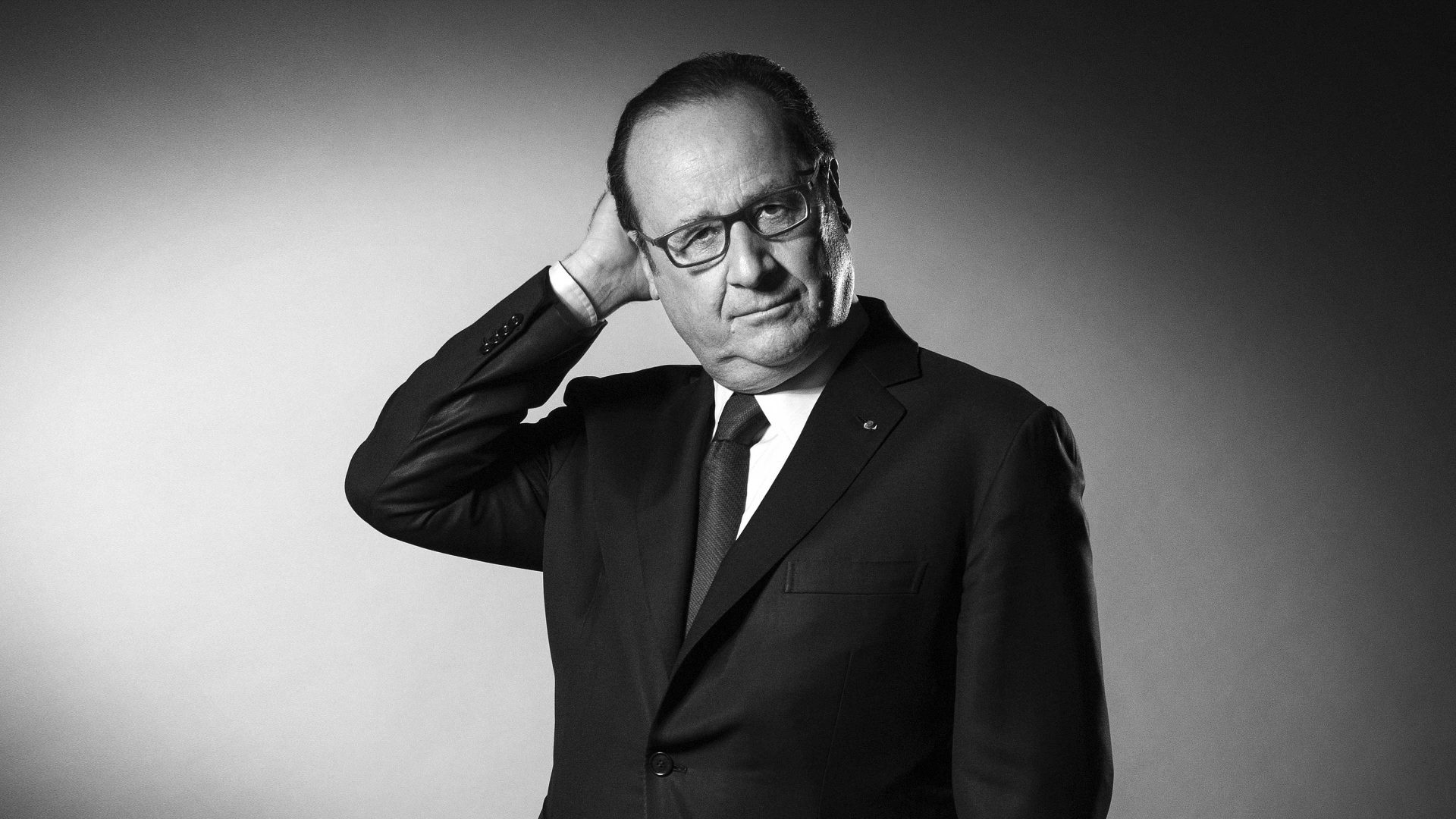

First, I should declare an interest. I really like François Hollande. He is among the more human, humane and humorous of the world leaders I have met. Even when, as president of France, his ratings were heading towards single figures, eventually leading him to the decision not to try to seek a second mandate, he never lost the ability to keep smiling, and keep others smiling too.

Second, full disclosure, I acted as an unofficial outside adviser for part of his presidency, a role we both kept secret, until it emerged in a book with whose authors he had cooperated, and whose title indicates they turned him over somewhat on his frankness and indiscretion: Un président ne devrait pas dire ca (A president shouldn’t say that).

So it was very nice to catch up with him last week, to chat over French politics, British politics, and the curse of populism in both, Ukraine of course, and much else besides. French media has been speculating he might yet stand in the upcoming parliamentary elections – unlikely, is my guess; as to what happens after that, what came through pretty clearly was that this is not a man looking at his political life in the rearview mirror, but one who continues to see a role for himself despite – or, perhaps, because of – the existential collapse of the Socialist Party in the recent presidential elections.

I point out that the French always seem to vote for presidents who promise change, but then revolt when the changes are made real – he laughs – which is a contrast to the UK right now where the public are remarkably tolerant of a prime minister who lies so much and delivers so little – he laughs again, this time his head nodding along. “What our election showed are the many divisions across France. The generational divisions are interesting… in essence you had young people voting for the extreme left, because they want radical change, and [Jean-Luc] Mélenchon, who is your Jeremy Corbyn figure, I suppose, was telling them they could have it; you had older people voting mainly for Macron, because they want stability and security; but the dominant force among people of working age is the extreme right, and that is about people saying ‘we want to be listened to.’ Holding the country together when your platform includes very difficult reforms, like pensions, for example, that is not easy with those divides and different demands.”

He is a youthful 67, so would be 72 when Emmanuel Macron’s second term ends. “So much can change in five years. France is a difficult country to govern anyway, but it has become more difficult. Macron will get a majority in the parliamentary elections, but it will be small, and the opposition will be extreme.”

Though Hollande is entitled to feel somewhat betrayed by Macron, appointed by him as a government minister before his young protégé left the party to set up his own, En Marche, he does not “blame” him for the demise of the Socialists. “The worst form of destruction is selfdestruction. The Socialist Party and the Republican Party must take responsibility for their fall. Macron’s win five years ago was an earthquake, but they didn’t react, didn’t adapt. He was dominant in the centre, and they had no real response so the debate to the left and the right of Macron shifted to the extremes. The traditional political landscape is shattered. We don’t have left and right any more. We have extreme left populists and extreme right populists, and Macron holds the centre. The centre left and centre right traditions have to rebuild, renew. That needs leaders, characters, people who can persuade and convince. We have to challenge populism not imitate it. Get better at digital, get better at speaking to and with young people.”

Yet is there not something odd about Mélenchon there, and Jeremy Corbyn here, being the people who speak to those young people better, older men with largely unchanged views set in the past? “People like to have a grandfather,” he says. “It’s the same with Bernie Sanders. Mélenchon is like a teacher. He explains the world to people who want it to be better, and makes them believe it can be done, easily. Corbyn was the same. Populism of the left.”

As for populism of the right, growing but ultimately rejected by the French, but in power in the UK, of the combination of Brexit and Boris Johnson, he says: “It has made the UK feel very, very distant… physically you are so near, a train ride away, but politically now you feel far, far away. We have a special link to the UK, which is crucial to European defence. We and you are the two strongest military powers. Even if you are no longer in the EU, the UK is part of European defence, but relations are not good.

“When Boris Johnson made the Aukus pact with America and Australia to replace French arms, that was really not a good way to treat an ally. It was not about losing the deal, but it revealed a lack of trustworthiness. France wants and needs good relations with the UK, but we need to see stability and seriousness. These are two serious countries dealing with serious issues so leaders need to be serious. And now, with the argument over the Northern Ireland Protocol, the sense we have is that this is not a serious way to address such a serious and sensitive issue.”

Decades ago, Hollande was a special adviser to François Mitterrand, and he argues that just as the former French president would be shocked at what his party and country have become, so would Margaret Thatcher about hers. “Mitterrand and Thatcher had very different politics, different personalities, but they wanted to achieve things together. The Channel Tunnel reminds us. Mrs Thatcher was a leader who maybe didn’t appreciate Europe, didn’t have the emotional attachment that we do, or the Germans do, she ‘wanted her money back’ but she was in Europe, and determined to stay there. She and Mitterrand would sit down at the same table together three times a year, at least. Today those discussions are not happening. Brexit has made Britain more distant.”

He believes that on both Covid and Ukraine, now on Northern Ireland, Johnson is driven by a desire to show the UK does things differently, rather than the drive for solutions that help the common good. “Britain has nuclear arms, you are on the UN Security Council, that makes you a power, but Europe is at 27, will grow, to 30, 35, and it is not good for either of us when Britain is absent from those discussions. Of course there is a special link between France and Germany, but that is mainly about things other than defence. On defence and foreign policy, losing the special link with the UK serves nobody well. It weakens both of us, Britain and Europe. It is one of the reasons Putin wanted Brexit to happen.”

The other European leader who comes in for sharp analysis is Johnson’s fellow populist in Hungary, Viktor Orbán. “He takes all he can get from the EU, the money, the power of veto to block things he doesn’t like. I only ever remember one intervention he made at a European Council, when he said he would not take a single Syrian or Afghan refugee. He does not respect the values of Europe, he is still close to Putin. I am not sure how long Europe can accept this. They fine Hungary, but he is happy to pay the fines and stay in. After Brexit, nobody wants to leave because they have seen how harmful it is.” He pauses, then laughs. “It’s a pity nobody wants to leave. ‘Go on, Viktor, there’s the door, just go!’ If they tried to expel Hungary, Hungary has the veto to block it! Crazy.”

Vladimir Putin’s name and influence weave their way in and out over the several hours of conversation on his recent visit to London. Hollande has considerable experience of the Russian president, not least when he, then German chancellor Angela Merkel and Ukraine president Petro Poroschenko sought to resolve a previous Ukraine crisis through the Minsk Accord.

“When I was elected in 2012, Putin was back as president after his spell as prime minister, after the first terms as president. He was in a mood of revenge. Revenge against the US. He considers it to be the fault of the US that the Soviet Union collapsed. He believes the US and Nato created a wave of force against him and Russia. That is his mindset.

“Then the crucial moment came in August 2013, Syria: Obama saying chemical weapons used by Assad was a red line, the red line is crossed, and nothing happens. Putin only understands force, he sees weakness, he exploits it. Syria, Libya, Crimea, recently in Belarus, Kazakhstan, in Africa too, where he has replaced French forces in Mali; then he observed withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan and the victory of the Taliban, and he realised he could attack Ukraine without a big reaction.”

Back in 2014, I remind him, he said that Putin would not be deterred by sanctions alone, but that a credible threat of force was required too, and today, Russia does not feel there is one. Dictators can stay the course longer than democracies. He half shrugs, half nods.

“We prefer peace. We don’t like war. If you ask a French person, do you support Ukraine? They say ‘yes.’ Do you think we should send weapons to help them? ‘Oh, not so sure.’ Would you support the sending of our own soldiers to fight there? ‘Never!’ That is a problem.

“Putin does not have to worry about his public opinion. He is not insane. I don’t believe he is at risk of being toppled. He will keep fighting until his objectives are met, or he can say they are met.” As for sanctions, Hollande suggests there is still a gap between the rhetoric of the west and the actual impact. “The sanctions create real impact on oligarchs, perhaps, but not on all the forces of the economy. It is harder for Putin, but their only resource is oil and gas, and he can sell his oil and gas to China and to other countries, no problem.”

He is scathing about Marine Le Pen and the other populists in France who took Putin’s support, and sang his praises, and still baulk at the action required to push him back. “There has been a real shift in this, it’s a new thing. In history, extremists have wanted to invade others, conquer, build an empire. Trump didn’t want to intervene anywhere. He was the best enemy Putin could have hoped for.

“In France, both the populist extremists on the left, and on the right, don’t want any intervention. I sent troops to Mali, planes to Syria. The extremists are always against it. Putin financed both extremes in France. Now they say they are against him but I will tell you now, when the war is over, they will say ‘we must sit down and speak to him, we must not humiliate him, we must have a new pact.’ In my view we should keep sanctions on including after the war, to keep the pressure on.”