They’ve sent Mayday signals and called British and French coastguards from their mobile phones. They’ve texted and called loved ones. Rescue must be on the way.

The dinghy is deflating so quickly, spilling them suddenly into the cold waters of the Channel. The water temperature is a little over 11C. The strong ones have perhaps four, five hours before hypothermia renders them unconscious. The weaker, the children and the old, have much less time. But time is not what’s going to kill them.

As fate will have it, the dinghy is sinking in the worst possible spot in the Channel; straddling the water border between France and Britain. Confusion is what will prove fatal. Confusion, and their dreams of a better life in Britain.

They fight to survive because that is what this desperate journey is all about. A mother and her three children – one, a young girl, just seven years old; a woman who made the journey for love; a teenager desperate to play for Manchester City; a brother determined to make enough money to pay for his sick sister’s medical treatment.

For several hours, they endure the unimaginable. Again and again, they call the coastguards on both sides of this narrow stretch of water.

The French tell them they’re in British waters: “You must call them”.

The British tell them they’re closer to France. Then, they tell them to turn on their phone torches so they can be found.

And no one comes.

At 9am, the shapes of their floating bodies, face down in the water, are spotted by another flimsy dinghy full of people just like them, people also sitting low in the waves as they strive to reach Britain. Again phone calls are made to the authorities. Still no one comes.

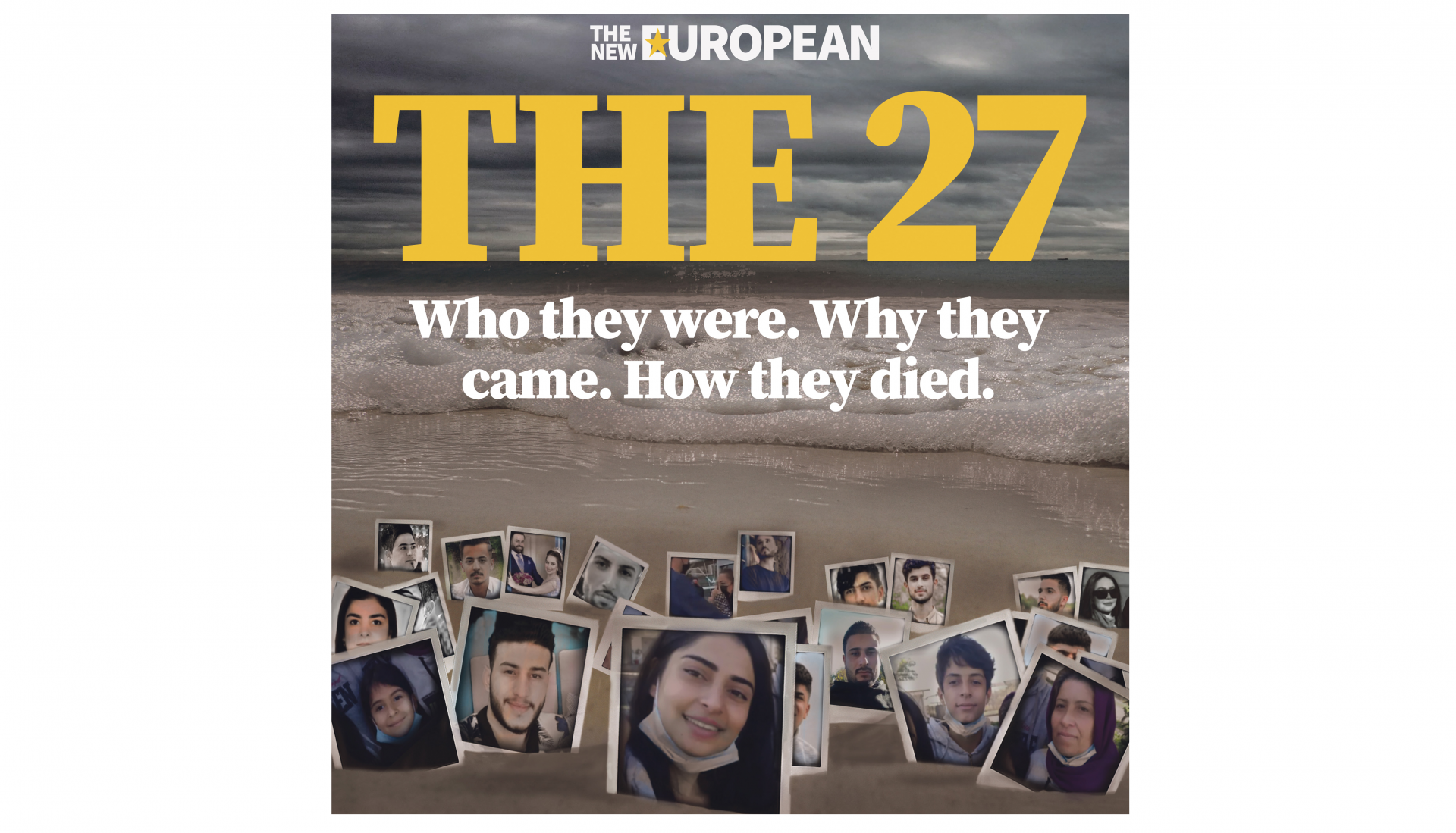

In the afternoon, around 2pm, a fisherman on a French trawler spots the bodies. The French coastguard at Gris-Nez puts out a Mayday call. Now the boats arrive. Twenty-seven bodies are retrieved. More have died, but the headlines around the world, in the brief days they merit space in the world’s news agenda, talk of 27.

Slowly, the terrible news snakes along the informal networks that govern the lives of those denied the luxury of the right passports, direct routes, and airport departure lounges. Much later, distraught relatives will report that three young men from Iraqi Kurdistan are missing.

At least 20 of the dead are from this troubled region, where a toxic cocktail of corruption, political repression, drought, poverty, financial mismanagement and conflict has pushed tens of thousands to seek asylum in the countries that once actively encouraged their dreams of independence, democracy and freedom from repression.

Authorities also identify three people – two women and one man – from Ethiopia, a country riven by civil war and famine; a woman from Somalia, where drought and conflict have blighted millions of lives; and a man from politically repressive Egypt.

Another four of the dead came from Afghanistan, a failing state driven to the brink of famine and collapse since the sudden withdrawal of US troops and the return of the Taliban to power.

Only two men survive; Mohammed Issa Omar, from Somalia, whose legs were burned by salt water and the film of spilled engine fuel on the sea water, and 21-year-old Mohammed Shekha, a shepherd from Qaladze in Iraqi Kurdistan. His voice cracks as he tries to describe what happened to a reporter from Kurdish broadcaster Rudaw.

“We started to hold each other’s hands. Each person holds the hand of the next person in order not to sink or drown in the water.”

Shekha pauses, looks up at the interviewer, his eyes wide, as if wondering whether anyone can really understand what this means. He swallows and continues.

“But with the sunrise, early in the morning, the people couldn’t take it anymore and they all gave up on their lives.”

THE JOURNEY

On August 10, Twana Mamand Mohammed packs his rucksack and leaves his home in Iraqi Kurdistan.

Out of school for over a year, the 18-year-old still hasn’t managed to find work. Hajiawa, a town in the Ranya district of this semi-autonomous region, is no place for an ambitious young man like him. Unemployment is at a record high and the political atmosphere is increasingly repressive. Isis militants – a rump force left after Kurdish peshmerga and foreign fighters defeated the main group – still carry out hit-and-run attacks, roadside bombings and kidnappings. A months-long drought has destroyed crops. The coronavirus pandemic and a drop in oil prices as the world went into lockdown in 2020 have only made things worse.

Twana, the second youngest of seven children, feels he has no choice but to seek a future elsewhere. Money is tight at home – his father earns a pittance as a daily labourer, hefting heavy building supplies, and his mother is a housewife.

Twana is not alone in wanting to leave. As the sun beats down on the sun-scorched fields and orchards of northern Iraq, others are also on the move.

Some 130 miles south, in Darbandikhan, Kazhal Ahmed Khidhir, a 46-year-old mother, ushers her three children out of the door and heads off, carrying their few possessions.

A few weeks later, on September 23, Zanyar Mustafa Mina, 20, from Sulaimaniya, begins his flight from government persecution.

Mohammed Shekha, who grew up just 40km away from Twana in Qaladze, embarks on a quest to earn the thousands of pounds his youngest sister, Fatima, needs for surgery. The eldest of six children, originally Iranians who moved to Kurdistan for work, he has lied to his parents about the journey ahead, knowing if he told them the truth they would stop him. Being the eldest, he is the apple of his father’s eye. Together with his brothers, he has raised £4,500 by working and mortgaging a small piece of land they own in Iran. It is, they hope, enough to get their brother to the UK, where he can earn enough as a labourer to fund Fatima’s hospital bills.

Over the next two months, 16 other Iraqi Kurds will leave their villages and towns in a region that has become a byword for both defiant bravery and devastating betrayal. The Kurds – an ethnic group of around 30 million spread across the Middle East – have campaigned for an independent state since the late 19th century, only to find themselves used and abused by powerful allies with little long-term loyalty. The oil-rich region has long been used as a playground by foreign powers, while Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein wiped out tens of thousands of Kurds by gassing and bombing their communities during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Iraqi Kurds have been repeatedly encouraged and then abandoned by the British and the United States governments, among others, as they sought to build an independent homeland.

Now, their current leadership is also letting them down. It is perhaps little wonder that so many decide that the only way to thrive is to seek sanctuary in those richer lands that once swore to uphold their dreams.

Twana, a taekwondo black belt and skilled footballer, dreams of playing for Manchester City. With the impatience typical of those with their whole lives ahead of them, he is itching to start his journey. His sister, Kale, is already living in Sheffield and so his father puts his home up as collateral for the journey, which will cost around £20,000.

Accompanied by two friends, Twana takes the overnight flight from Erbil, Iraq’s Kurdish capital, to Istanbul.

In Turkey, the three friends decide to try to cross the border into Bulgaria. It’s a well-known route into Europe so they feel fairly confident. Usually, smugglers help people cross the border and then arrange cars to take them to the capital Sofia, then on to Serbia.

But it is not to be for Twana and his friends. They are caught at the frontier and deported back to Turkey, but not before the border guards seize all their valuables – money, phones, even their belts. Discouraged, the men regroup in Istanbul. It will be weeks before Twana makes another move, and this time he decides he will travel by sea. For now, he lays low in Istanbul, plotting his next move and meeting some of the people who will eventually join him on Loon-Plage beach outside Dunkirk where they will board a flimsy dinghy for the final leg of their defiant journeys on a cold November night.

At the beginning of October, Twana heads south along the Aegean coast until he is just outside the seaside town of Izmir, a region more usually peopled by holidaymakers. A boat is waiting to take him to Europe and clambering in alongside him is Kazhal and her three children, and a group of the young Kurdish men he met in Istanbul.

Kazhal leaves Darbandikhan in August with her daughter Hadya, 22, son Mubin and little Hasti, seven. Their house has been sold by Kazhal’s husband, Rizgar Hussein, to pay for their journey – raising around £50,000. Rizgar is staying behind. He was a policeman and he hoped to join his family later when they make it into the UK. Hadya, a tall young woman with striking eyes, hopes to study art, while Mubin wanted to improve his English and become a barber.

The youngest, Hasti, with her ebony tresses and winning smile, is just happy to be with her mother.

Young people with the courage to try to escape the existence fate dealt them, Hadya and Mubin must have felt so frustrated by the state of education in Kurdistan, a place where the power of two ruthless political families means that the job you get depends on who you know – a bleak outlook for the nearly 50% of the population who are under 20. State schools are under-resourced and overlooked by politicians, and the few private schools available are expensive and out of reach.

On the very day that Hadya, Mubin and Hasti board the dinghy at Loon-Plage, Kurdish police were firing warning shots and tear gas into crowds of students protesting in the city of Sulaimaniya, demanding the restoration of financial support for university students after a six-year freeze. Ironically, the next day, when Kazhal’s children are drowned, the authorities of Kurdistan will commit to restoring some of that money.

For now, as they settle nervously into the smuggler’s boat in Izmir, their hearts are full of the promise of Europe, dreams nonetheless diluted by fear. The journey must have seemed so daunting – the sea so large, the danger so present – but they had got this far and surely this new friend, Twana, alongside them in the boat, will have told them that the route overland was a no-go, that they made the right choice.

Four days later, they land in Italy, but the country is in lockdown. They are forced to stay put for 11 days, before Twana and his friends eventually continue overland to Paris.

Twana poses in front of the Eiffel Tower for a photograph on October 25. He sends the picture to his 33-year-old brother Zana, a police officer back home in Hajiawa. The pair have stayed in touch all through Twana’s long journey.

On October 26, Twana leaves Paris behind for a much grittier reality – the ad-hoc camps along the coast of northern France where those hoping to get to Britain eke out desperate existences under thin canvas tents as they wait to make an all-or-nothing dash across the sea.

He’s been on the road now for more than two months. He is ready to take his chances in the Channel.

How surmountable that sea must have seemed – just 21 miles at its narrowest point – to a young man who had travelled over 2,300 miles as the crow flies from his home in the foothills of Iraq’s Qandil mountains. On clear days he can see the white cliffs of Dover. The end of his suffering is so close.

Over the next several weeks, the teenager tries six times to make it across. Each time he is foiled.

Little does he know that across the Channel in Britain, pressure is building on Boris Johnson’s government to act on what some politicians and media describe as a “surge” of people crossing the sea. It is true that new records are being set; more scared, cold people are arriving in flimsy boats on the beaches of Kent than in previous years, but this is partly because other routes have been shut down and, in any case, the numbers are still far below those seen in other countries. In 2021, around 67,000 people arrive by sea in Italy and around 40,000 disembark in Spain, compared with 28,300 in the UK.

Between attempts, he lives in the Grande-Synthe camp, a collection of tents and ramshackle shelters on the outskirts of Dunkirk, a few miles up the coast from Calais, where Kazhal and her family and all the other hopeful people from Kurdistan and elsewhere have been marking time as they stare across the sea, waiting for their moment.

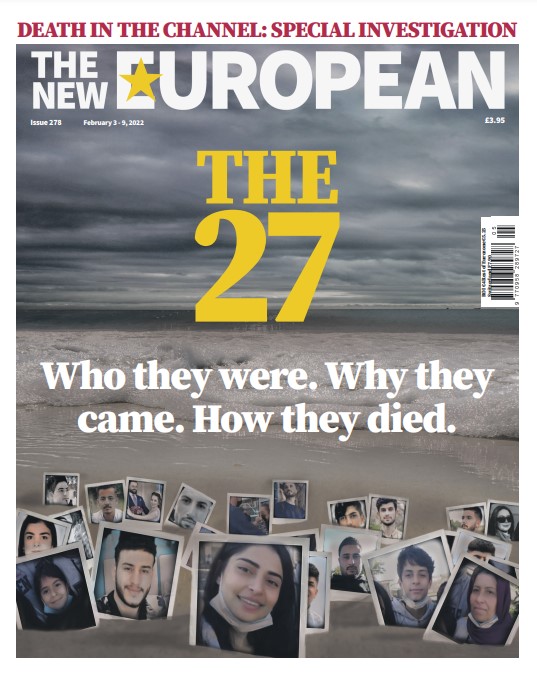

There is so much we cannot know about their time in the camp – these lives lived in limbo are too often reduced to statistics and described only in the collective – but in the case of Kazhal and her children, a haunting record does remain.

One day, in Grande-Synthe, they meet photographer Abdul Saboor, himself a refugee from Afghanistan. It’s cold and wet and just a few days before they will make their final attempt to cross the Channel. Saboor finds them trying to rebuild their tiny world after French police raided the camp. Their tent has been destroyed, their meagre belongings taken.

Saboor finds Kazhal, in a grey sweater and hoodie, tending a fire. Mubin sits on a camping chair, his hand in a tube of crisps, talking to little Hasti.

“I met them in the camp, there had been an eviction and everything had been cleared. Kahzal was going to get some water for the children,” Saboor says, his voice filled with sadness.

Kazhal, the hood of her sweatshirt pulled firmly over her headscarf, posed for Saboor, who photographed her leaning on a shopping trolley in the middle of a grassy wasteland strewn with rubble. She was squinting slightly in the winter sun, a wistful expression on her tanned face.

She reminded Saboor of his mother. When he got home, he called her in Afghanistan. He needed to hear her voice. Kazhal’s family made a deep impression on the young photographer. He tells us that, even two months later, he can’t stop thinking about them. “They didn’t have anything. But Kazhal had made a fire and gave me tea and food. The boy, Mubin, gave me some crisps. I said, ‘no, you have nothing, what are you going to eat?’ and he said, ‘don’t worry, my mum will get something.’”

Saboor said Kahzal was so tired she could barely speak, but she was trying to keep everyone’s spirits up. The children looked happy, he remembers. “They thought they had made it to Europe. You could see it in their faces. They told me they were going to learn better English. He said he wanted to be a barber. She wanted to be an art teacher.”

The excited children ask if the weather in Britain is as cold as it is in northern France. They tell Saboor and the British reporter with him that they have an aunt in the UK, and they are looking forward to joining her. Then the journalists ask Kahzal if she is worried about crossing the Channel – after all, this will not be their first time so, unlike many who arrive on this coast, she knows the danger, she has seen the waves.

“It’s dangerous. I’m very scared,” Kazhal told them. “The thought of going on that boat with my children worries me every minute. But look at where we are: we cannot stay here. We have no water, no tent …”

And so, Kazhal decides to try again – to risk the waves because life in France is unbearable and they are so close, so very close. She and her children head to Loon-Plage on the evening of Tuesday, November 23 and as they wait to set off, Hadya sends a message to her father, Rizgar.

“Dad, in five minutes we will leave. Everyone is getting in the boat now. Dad, we’re getting in.”

The message is the last contact Rizgar has with his family.

Kazhal and her family settle themselves into the 10-metre dinghy, scooting along to allow others to squeeze in. Perhaps, they exchange a few words or even shy smiles with Maryam Nuri Mohamed Amin, a 24-year-old determined to join her fiancé, Karzan, a barber in Bournemouth. Perhaps Maryam shows them a photo from the young couple’s engagement party in January; in it, she is wearing a lavender dress and a tiara while a beaming Karzan holds a bunch of deep pink flowers.

Unlike Kazhal and many of the others in the boat, Maryam, whose nickname is Baran or ‘rain’ in Kurdish, has had a relatively straightforward journey to this cold beach. Just three weeks before, on November 2, she left her home in the town of Soran – some 70km north of Twana’s home – and travelled to Europe. She has a Schengen visa, which allows her to travel throughout the EU’s passport-free zone for three months. But she had not been able to get a British visa before her trip – despite Karzan’s British citizenship and presence in the country.

Maryam’s family said she had tried to reach the UK legally twice and that she had been to the British embassy but the process was “delayed”, forcing her instead to take the route she did. Iraqi Kurds in the UK tell of months-long delays as they wait for a visa applications’ process that is prohibitively expensive, even if they have legitimate reasons to come to Britain. This situation has been exacerbated by delays caused by the pandemic and lockdowns.

And so Maryam decides to try the only alternative left. Travelling with two other women, she takes a flight from Kurdistan to Turkey and then changes straight on to a plane for Italy. Overland, she heads to Germany, where she meets Mahabad Ahmed Ali, a woman from Erbil. The 32-year-old’s husband is also in Britain. He knows Karzan. The women become friends, and together, they head to France.

So far so good. But then they hit the implacable barrier of the Channel. Maryam finds herself in Grande-Synthe, within sight of the land where her fiancé is working hard to build a life for them both.

Maryam, who is still a student in Kurdistan, is done with waiting for her life to begin. A week after arriving at the Grande-Synthe camp, she decides to surprise Karzan by crossing the Channel. It’s a leap-of-faith decision. A final roll of the dice. An act of love.

Her cousin Iman Hassan tells France 24 that Maryam takes a selfie on the boat and sends it to Karzan, with the words “I’m coming to you”.

“She was so romantic. They loved each other so, so much,” Iman says. In that last selfie, Maryam looks nervous and hopeful and very, very young.

Twana too is getting impatient. He was supposed to make another attempt to cross the Channel on November 24 but at the last moment, he decides to bring his journey forward by a day. He calls his brother Zana in the morning to let him know.

Zana vividly remembers this last conversation with his brother. “We talked about the boat, the state of the motor, who would be travelling with him,” he tells us on the phone from his home in Iraqi Kurdistan. “Twana said there was no problem, he said the motor is OK, the driver is a professional sailor.”

Twana wants to leave as soon as possible: “Please, I am sad here,” he pleads. “The French police came and destroyed our tents. They don’t want us to stay in France so we will leave this night.” Zana agrees.

Twana and the young men he befriended on his long journey – including some who were on that boat with him from Istanbul – reportedly agree to pay £2,350 per person to cross that same evening.

They head to Loon-Plage where they join Maryam, Kazhal, Hadya, Mubin, Hasti and the others.

Also waiting on that cold beach is Bilind Shukur, 21, who travelled from Kurdistan to France via Syria, Baghdad and Belarus, taking advantage of easy visas being offered by President Alexander Lukashenko. The troublemaking Belarussian is using the new arrivals as pawns by luring them in and then pushing them towards the Polish and Lithuanian borders. It’s a brazen bid to destabilise the European Union but it is the Iraqi Kurds and other travellers who suffer most, clustered in the freezing forests on the edge of a promised land they believe will deliver the freedoms and rights they have been denied at home.

Many who put their faith in the Belarus route are thwarted as the Poles put up barriers and push them back. Several die in the woods. But Bilind makes it through and then stays with a relative for two weeks in Germany before heading on to France. Phone footage, shared by Rudaw, shows a young man with a sharp haircut and piercing dark eyes hugging family and friends goodbye, then sitting in a crowded bus during his travels.

Shukur’s journey began on October 27 when he left his home in Zakho on the febrile Turkish border. Part of the mountainous region of Dohuk, Zakho has many scenic hiking routes, but they are often unreachable because of fighting between the Turkish army and separatist Turkish Kurdish militants. Like many others, Shukur had help from smugglers, including one called Majid, also from Dohuk. A talented hairdresser and regular gym-goer, who liked playing music with his friends, Shukur had family and friends living in Canada, the UK and Europe, and wanted to go too.

He wasn’t really supposed to be on that beach though. Much like Twana, his plans changed at the last minute. His original agreement with Majid was for a crossing in a lorry, but the smuggler had called him to say that the border police had brought in sniffer dogs, and nobody had managed to cross that way for more than a fortnight. It was the dinghy or a wait of several months.

When Bilind left home, he told a friend: “Tell anyone whom I have wronged to forgive me”. This phrase is often used by Muslims when they are about to die.

INTO THE CHANNEL

It is around 10pm when they push off into the grey, cold sea. Even by November standards, the sea is cold; 11.6C. There is no rain, but the air is bitterly cold, around 7C with a stiff wind funnelling down the Channel from the south.

The boat is flimsy – a French official later dismisses it as a “paddling pool” – but Twana is upbeat. He has told Zana that the boat has space for 45 people – others will say later it should only carry 20 – but because 33 people are aboard, the teenager thinks this a good sign. He sends Zana a Facebook message to say they are good to go.

Also buoying his spirits are his friends – a group of men in their teens and early 20s. Some of them he knew back home – including “Harem” Sarkawt Pirot Mohammed, the 28-year-old cousin of Zana’s wife. Harem, a good swimmer, is determined to get to the UK where his brother Anwar, a Sheffield University graduate, is living in Cambridge.

Harem travelled with Twana from Istanbul, as did Mohammed Hussein Mohammed, 19; Bryar Hamad Abdulrahman, 23; Shakar Ali Pirot, 30; Hassan Mohammed Ali, 37, and Sirwan Alipour, a 23-year-old from Sardasht in north-west Iran.

Like many other Iranian Kurds escaping political repression and economic decline, Sirwan left in September, crossing the border to Turkey and travelling the length of the country to the western coast, where he took a boat. After five days at sea, he landed in Italy, and slowly wound his way north to Calais, arriving in early October. He had paid $13,500 for the journey so far and would pay a smuggler a further $3,500 to take him across the Channel. Sirwan had tried and failed four times before boarding the doomed vessel that Tuesday night. During one attempt, his phone stopped working due to water damage, but he told his father he could use his friend Shakar’s this time.

Also squeezing into the boat are Pshtiwan Rasul Farkha, 18 and Afrasya Ahmed Mohammed, 27, two men Twana had met in northern France.

It must have seemed like such an adventure – everything is an adventure when you are so young as to feel immortal. They’d all done this before and although failure was possible, so too was success. Even if they didn’t make it all the way across, they could always try another time. It’s the kind of thing young men are apt to joke about.

As Maryam settles in, perhaps she exchanges a few words with another Iraqi Kurd, 19-year-old Muslim Ismael Hamad? Perhaps she even recognises him, for he too is from Soran even if his journey has been entirely different. He flew from Erbil to Turkey on October 31 – just a few days before Maryam. But, instead of continuing straight to the EU, he took advantage of Lukashenko’s visa scheme and went to Belarus, eventually walking across the border to Poland. He then drove to Germany and there he rented a car to drive to France.

In France, Muslim stayed at the home of a family friend for one night and then took a train to Dunkirk, his father Ismael tells us. His goal is to join his friends and cousins in the UK.

Muslim’s father didn’t want him to go. But in the end, he could not stop the second oldest of his seven children from leaving. Muslim had left school at 13, had no profession and was not working. But he believed that he could become skilled and productive in the UK. “One day he sat me down, saying, ‘Dad, I want to go’. And he put his arms around my neck, and in that moment, I couldn’t say no to him. His mother said, ‘let him go, everyone’s going anyway. Nothing will happen.’ And I did,” his father says.

The boat is starting to fill up. Zanyar, the young man who left to escape persecution, is also on board. He too might be thinking of the father he left behind. Local security forces had accused Zanyar’s father of organising anti-government protests and Zanyar himself was facing abuse. It was a dangerous situation.

“That was the main reason he left,” Zanyar’s father, Mustafa, said. “The second reason was he could not find a job here and then his friends had also left before. He flew to Turkey first, where he stayed for one night, and then he took a boat to Italy, and then the train to France. He tried to cross the channel seven to eight times, but it never worked.”

Two friends Zanyar made on his long journey – Mohammed Qadir Awlla, 21, and Rezhwan Yassin Hassan, 19 – are beside him. There is safety in numbers, surely.

Other friendship groups have formed as these desperate young men sought comfort on their journeys.

Mohammed Shekha, who will survive what is to come, has become close to Twana over the previous weeks even if his route to this dark, cold beach was very different.

Mohammed travelled overland from Qaladze to Damascus in Syria and then flew to Minsk in Belarus before crossing to Poland. He travelled by road to Germany where he was arrested. He sought asylum and was put in a hostel. But he decided to make a break for France and took a train to Paris and then to Dunkirk.

Over the following hours, as they make their way across the water, Twana and his friends stay in touch with Zana and their sister in Sheffield. For a while, there is only good news to report. But in the early hours of the morning, the right side of the boat starts to deflate and water starts seeping in.

At around 1.30am French time, Maryam messages Karzan on Snapchat and says the boat is losing air and taking on water. But she seems calm and reassures him that things will be fine. She’s sure someone will come and rescue them soon. They are still talking when she drops off Snapchat.

Twana too is initially unfazed. He’s done this before. He knows the drill. People on the boat start calling the French and British coastguards. Among them, 16-year-old Mubin, using his nascent English. They are confident they will be rescued. They are, after all, in the busiest shipping channel on the planet.

“They phoned the British police who said, ‘please turn on the lights of your cellphones so we can see your boat’,” Zana says, his voice angry, his speech rapid. “They turned on their lights but no one saved them and so again they called the French police and then the British police.”

During the night, Bilind tells his anxious father not to worry and to go to sleep. But his last voicemail raises concern: Bilind says he must turn his phone off so as not to upset the smugglers; the voice of a woman speaking Kurdish can be heard in the background, saying: “Oh my god, why has the water turned this way?”

Around 2.30am the engine breaks down. Twana calls his sister in Sheffield and tells her about this new setback. He is still calm, though, and says the broken motor is no big deal.

But he asks her not to call him back because they have been told by the British coastguard to turn on their phone lights. Someone’s bound to be coming, he says. She might as well go to sleep. He’ll be in touch when he gets to England. But now, disaster strikes. The deflating boat sinks in 30 frantic minutes and its passengers slide into the icy waters of the Channel.

At around this time, friends Sirwan and Shakar message Sirwan’s father, Abubakir Alipour, who’s waiting anxiously for news in Iran.

The audio message sent at 3.42am French time is the last message anyone will receive from the boat.

“Honest to God… we are in British and French waters. We don’t know which one of them is coming to [rescue us]. I’m throwing away my mobile. If you don’t hear from me, that means we are in Britain and if I return to France, then I’ll call you myself,” Shakar says.

In the background, people can be heard whistling as they try to attract attention. According to marine tracking data and official accounts, analysed by Sky News, both France and Britain had boats in the water between Calais and Dover around 3am, the time the dinghy sank. The ships include HMC Valiant and Flamant of the French navy. A French fishing boat, the Saint Jacques II, is also heading north into the Channel. Forty-five minutes later, a UK coastguard helicopter flies above the area. For whatever reason, the dinghy is not spotted.

Survivor Shekha later tells his version of what happened from the moment the boat first started to deflate: Some passengers try to pump air back into the balloons on the right side of the boat, but the pump doesn’t work properly.

They call the French and send them their location, but they’re told they should contact the British as they are in British waters – that French boats can’t come to rescue them.

So they call the British but still no one comes. People start to lose hope. The waves begin pushing them back towards France. And then the boat disappears from beneath them. The remnants of the craft are later photographed in the sea, a few pathetic folds of rubber that hours earlier cradled the hopes, dreams and lives of all these people.

Everyone sinks into the waves, and holds hands, as they wait for a rescue that will never come.

THE AFTERMATH

The first bodies are spotted at 9am the next morning. Another boat full of people comes across them as they try to accomplish what the victims couldn’t – to get to the UK. They call the French authorities. But it isn’t until around 2pm when Karl Maquinghen, the second-in-command on the Saint-Jacques II, notices the shapes of bodies floating face down in the water that an alarm is raised. The French naval boat Flamant is just two miles away at this point, while the Border Force boat Hunter is in UK territorial waters, just over four miles from the French fishing boat.

“Seeing so many dead like that next to us, it was really like a horror movie,” a shaken Maquinghen says afterwards.

The French coastguard at Griz-Nez puts out a Mayday call with the coordinates for rescuers. The drowned are marginally inside French waters. Over the next hours, 27 bodies are recovered. Miraculously, Shekha – who cannot even swim – and Issa Omar are found alive and rescued.

At least three of the young men who placed their lives on the line to complete this perilous journey together are missing: two of them are Zanyar and Pshtiwan. More than two months later, at the time of going to press, their bodies have still not been found. Twana’s body, too, is never recovered.

WHY THEY RISKED IT ALL

So many of the drowned came from Kurdistan. For some, it was love and family ties with the UK that drove them into the dangerous waters. For others it was the corruption back home, the nepotism, the oppression, and the economic collapse of their land since a defiant referendum for independence in 2017 backfired, angering neighbours and erstwhile allies.

The Iraqi government retook the symbolic – and economically vital – city of Kirkuk while Turkey, which had historically cooperated with the ruling Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), became belligerent and dangerous. A damaging split between the two main Kurdish political clans – the KDP and former president Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) – widened.

Erbil’s foreign allies, including the United States, were furious at the nature and timing of the referendum and at the KDP’s rejection of a UN-mandated diplomatic deal.

The US and Britain had helped set up the autonomous region after Western allies defeated Saddam Hussein in the 1991 Gulf War. The Kurds and the Shi’ites, encouraged by the US, rose up against a leader who just three years before had used chemical weapons against them. They were slaughtered, and survivors fled to the northern borders. Horrified, the then British prime minister John Major suggested a Western-enforced no-fly zone above part of northern Iraq, so the Kurds could be protected.

This helped to establish a de facto state, and Iraqi Kurdistan had been effectively self-governing since.

When Islamic State roamed Syria and Iraq decades later, the US looked to the Kurds to help defeat the group. But after their success against Isis, the seemingly unassailable rise of the Iraqi Kurdish state – so long encouraged by Western capitals – was suddenly a diplomatic inconvenience. In geo-politics, incentive is everything and the incentive for the West to support an independent state disappeared with the defeat of Isis.

Although Kurdistan is still rich in oil, the economy is shattered. Many in the state sector – and some in the private sector – are not being paid their wages. To quote one man, a 30-year-old who, like Twana, took the Turkey-Italy route to France, the region is an “iron prison built by family ties, traditions and a political regime that has turned Iraqi Kurdistan into a place with very bad economic and social conditions”.

Turkey regularly launches bombing raids here, targeting the militants of its own secessionist PKK, but often killing and wounding civilians. And what’s left of Isis remains a threat, as Twana’s brother, Zana, explains.

“When we sleep, we sleep under the rule of the government but none of us has it guaranteed that when we wake up tomorrow, Isis won’t be ruling us. That was another reason why Twana left; otherwise, no mother, no father, no sister, no brother would want for their brother to leave with smugglers and live in exile.”

AN INDICTMENT OF WHOM?

The November tragedy was the worst of its kind in the Channel. It stands as an indictment, not just of the failure of the two coastguard services to rescue these terrified people during their hours of agony, but also of France and Britain’s failure to deal with migration more broadly in a humane and coordinated way.

From the violent destruction of ad-hoc camps like Grande-Synthe by French gendarmes to the UK government’s plans to criminalise those who survive the deadly sea journey, the official approach on both sides of the Channel has been reactive and aggressive.

Those in power do not seem to want to understand the complex forces driving this movement of people.

It’s much easier to make populist political capital out of the human tragedy. And without understanding, there is little hope of enlightened or effective policy-making.

As long as authorities focus on brutally pushing back the needy and vulnerable and young and hopeful, as long as they cut off the lifeline of safe routes to seeking asylum, there will be no end to either this movement or tragedy.

Take the narrative created around Shekha, one of the two survivors. His trip cost him around €10,000. Speaking in the National Assembly just days after the tragedy, French Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin said that Shekha hoped the money would buy him a better future.

But that isn’t the whole story, nor even the right story.

Shekha wanted to get to England to earn money to pay for his sister’s medical treatment.

“She has an illness that needs a lot of money. I said I will go to Britain to make some money and will take her to India for treatment. This is my only reason for migrating,” Shekha said.

There is much bitterness towards France. Mohammed Ahmed Khidhir, whose sister Kazhal perished that night with her three children, is furious at the French for their apparent indifference, their lack of care.

“If you were my guest, I would warmly welcome you. France knew these people were going to cross the Channel,” he tells us. “Why did they not deport them or not let them in their country? Why did they leave them to die in the waters of the English Channel?”

Without question, smugglers also have a role to play in this cruel lottery. They can be callous and unscrupulous. Muslim’s father, Ismael, tells us that his son ended up on the doomed boat because he was essentially traded between smuggling groups looking to make up their quota for a night-time trip.

Ismael says he has evidence that a smuggler from Soran “sold” Muslim on to two other smugglers for $1,500 – half the agreed price for the crossing.

“The first smuggler did not have anyone to board that night. He sent a message to the smugglers’ group saying ‘I only have Muslim to board, who wants him?’ He sold my son,” Ismael said.

French media reports say at least five people have been arrested in connection with the November 24 tragedy. Survivor Shekha, who is now lying low, says he has been threatened by the smugglers since the boat sank.

Smuggling networks are firmly embedded in places like Kurdistan. Travel agents connect people with smugglers in Turkey and elsewhere and take deposits for sea crossings. The final payment is only due if the journeys are successful.

But human rights activists say the smugglers are by no means the only villains. These networks thrive because of the lack of alternative, legal routes for people to get to countries such as the UK. British visas are incredibly hard for Iraqis to obtain, even for those who apparently have a straightforward claim to one, and there is no facility for them to apply for asylum at embassies in their own or other countries. They have to get to Britain if they are to try, the ultimate Catch 22.

AN ACCIDENT OF GEOGRAPHY

Where one is born, they say, is merely an accident of geography. That this fact – and its attendant consequences – can dictate where and how one dies is the tragedy at the heart of this story.

Britain and France try to lay the blame for what happened that night at the door of the smugglers, but the bereaved know better. They have grief enough to encompass the vast array of actors who let their loved ones down as they begged for help.

Some families have initiated legal proceedings with their lawyers saying “serious failings” in the rescue operation may have contributed to the deaths.

In the UK, lawyers for four families – including those of Twana and Sirwan from Iran – are calling for an independent public inquiry to uncover what went wrong, along the lines of that granted the victims of the Hillsborough Disaster.

The law is different in France, which allows for more aggressive action. Utopia 56, a migrant and refugee charity, has filed a judicial complaint accusing the British coastguard, the maritime prefect of the Channel and North Sea, and the Regional Operational Centre for Surveillance and Rescue of Gris-Nez in the Pas-de-Calais of “involuntary homicide and failing to deliver help”.

The Home Office has denied claims that British authorities failed to respond to distress calls, saying the incident took place in French waters.

In a statement, the Maritime and Coastguard Agency said on the day of the tragedy it received more than 90 alerts in the Channel and responded to all of them.

Dan O’Mahoney, the Home Office’s Clandestine Channel Threat Commander, told a parliamentary committee after the disaster that it “may never be possible to say with absolute accuracy whether that boat was in UK waters or French waters prior to that.” He also could not say with certainty whether the coastguard definitely received a call from the sinking dinghy.

The French maritime authorities said they first knew of the disaster when the bodies were spotted, although Le Monde newspaper quoted judicial sources as saying distress calls were received by both French and British rescue services.

Twana’s brother Zana notes that the people on the boat were wearing life jackets and says he saw medical reports indicating that it was kidney failure, caused by the many hours spent in the sea, that proved fatal for many of them.

Charlotte Kwantes, coordinator at Utopia 56, told us their lawyers based their case on the survivors’ testimonies and related information from their own volunteers.

“There are specific regulations between both countries that ask for coordination to make sure that people at sea are rescued whatever waters they are in,” she said.

Utopia 56 and the families believe that if the Mayday call had come from people not identified as “migrants” then they would have been rescued. The main aim is to “know the truth and ensure that it never happens again,” Kwantes said.

Maryam’s father, Nuri Hama Amin, a fighter who battled Isis as part of the US-allied Kurdish peshmerga forces, believes the boat was in British waters. But he blames both countries for his daughter’s death.

“These people on the boat, Baran, and all the others, they were humans, they have parents and families. Based on the words of Mohammed [Shekha], they called both the British and French guards but no one went to their rescue. Who do I blame this tragic incident on? It was God’s decision but the most guilty in this are both Britain and France.”

It might seem inconceivable that people would risk their own lives and the lives of their children on such a dangerous journey, but to understand why one must balance the certainty of oppression or deprivation at home with the possibility offered in the chosen destination.

For example, an analysis by the Refugee Council, published barely a week before the Channel tragedy, found that the people who make this journey are likely to be allowed to remain in the UK as refugees, with just over a third of those arriving not being deemed in need of protection. Based on statistics from January 2020 to May 2021, the study found that 91 per cent of the people who came across the Channel were from just 10 countries, including Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Eritrea, Yemen and Afghanistan.

According to the Home Office, 98 per cent of these people apply for asylum and, for the top 10 countries of origin, 61 per cent of initial decisions made in this period would have resulted in refugee protection being granted.

So this is not a crisis of numbers. It is a direct result of shutting the door on other ways to claim asylum – a universal right under the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention, to which Britain is a signatory.

Boris Johnson’s government seems determined to create ever tougher deterrents. For example, the Nationality and Borders Bill, currently in the House of Lords, would make it a criminal offence to knowingly arrive in Britain without permission – a provision that is illegal under refugee law.

In a New Year’s video, Home Secretary Patel said she would prioritise fixing “our broken asylum system”. The Nationality and Borders bill would deliver the necessary powers to do that, she said. “A fairer system deterring illegal entry across the Channel by cracking down on people smugglers and ending the legal merry-go-round of spurious asylum claims is what the British people expect and we will deliver.”

For the thousands of people waiting in squalid camps around Calais and Dunkirk, Patel’s policies will offer little deterrent. It doesn’t help either that relations between Britain and France have been strained by Brexit, the AUKUS submarine row and some tetchy, even juvenile verbal sparring between Johnson and President Emmanuel Macron.

For Zana, the politics are unimportant. If possible, the loss of his brother Twana is all the more agonising because there is no body.

His parents do not have a grave to pray over on Fridays. They cannot fully grieve. All they have is the secondhand story of his final hours and the heartbreak of unanswered questions. Zana asks if someone might launch a campaign to find his brother’s body and the other missing boys.

It’s hard to answer this question because it has been too, too long already but hope is all Zana has now.

“I feel sad but mostly I feel angry,” he says. “I am sad because I have lost my lovely brother and… I don’t know if he’s alive or dead. Also, I am angry because the European governments talk about human rights and humanism, but now we realise that there is no humanism, there are no human rights in European countries. If there is, why didn’t they come and rescue them?

“For five hours, no one died but after that they died because of the cold. The British say the careless one is France, and France blames Britain. So why do they blame each other? Why do they not talk about humanity? Why did they not rescue these people?”

JOURNEY’S END

On December 26, the airport at Erbil in Kurdistan is packed with hundreds of people. But this is the worst kind of homecoming. Women in black shawls are crying. Rizgar, who lost his entire family, sits with his head in his hands. Maryam’s mother faints into a metal chair, while Karzan stands with a photo of Maryam pinned to his chest.

It is the most awful of vigils as the families wait for a plane bringing 16 bodies from France.

At around 4.30am, ambulances carrying the bodies from the plane begin to arrive outside the airport. The mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers come out into the bitter cold, running to place their hands tenderly on the backs of the vehicles. One ambulance is draped with a poster of Maryam.

Zana is at the airport too, even though he knows there is no body for his family to collect. He helps other grieving families deal with the authorities. He tries to sort out the paperwork and make sure people know what they must do.

Then, finally, the bodies are driven away to be buried. Thousands of miles from where they wanted to be, 16 men and women and one little girl complete a voyage that was never meant to be circular.

This is the end of an odyssey of hope inspired by the belief that everyone has the right to a future, that geography should not be destiny.

Under a bright blue sky in Darbandikhan, Rizgar sits on a low wall in the graveyard and watches as a digger drops bucketfuls of earth on to the coffins that contain his whole world.

As well as original reporting, this story draws on articles and footage from Rudaw, Sky News and the BBC, as well as other media outlets. Layal Shakir conducted some of the interviews and Giacomo Sini and Alessia Manzi also contributed material.