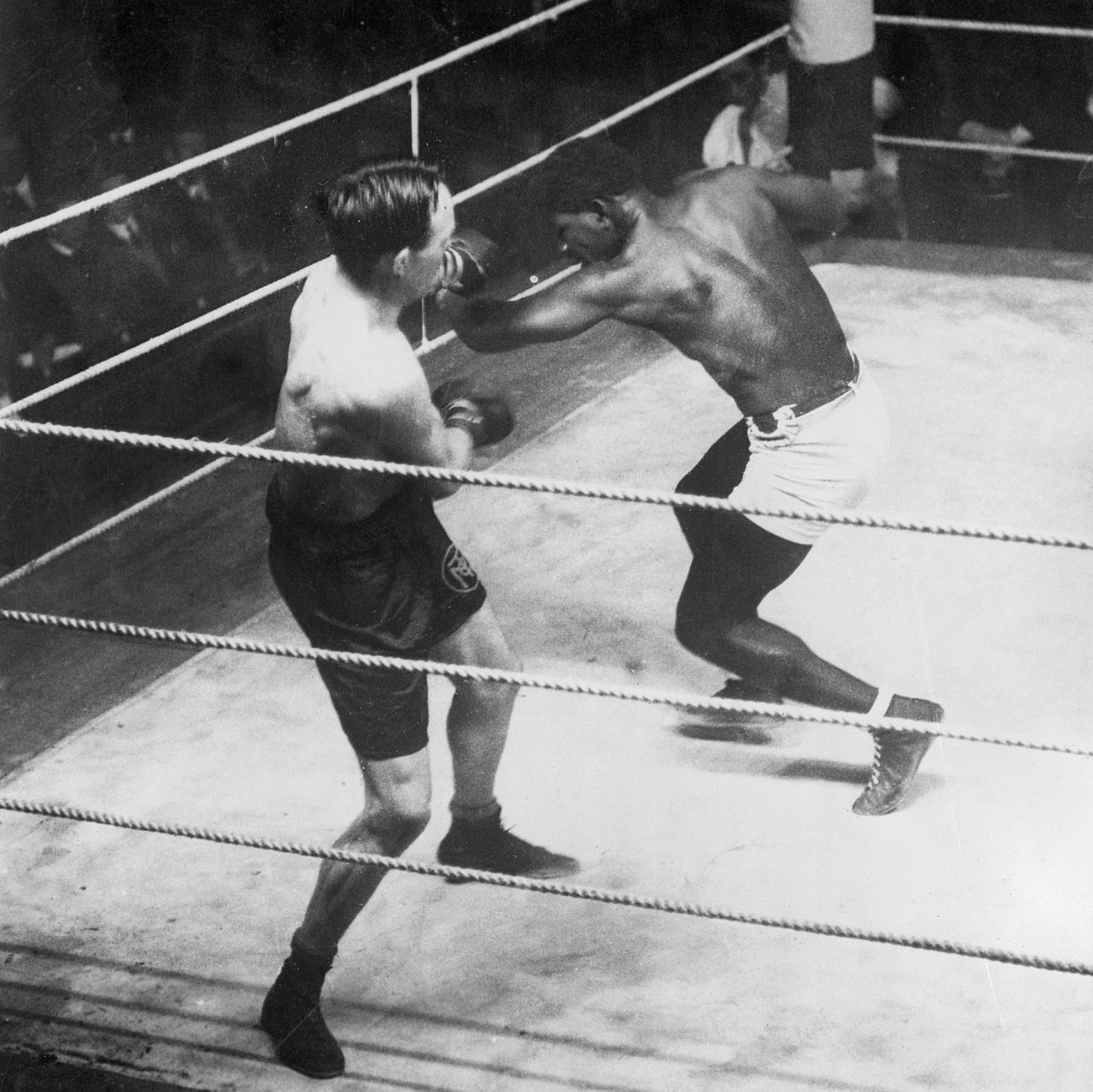

In one corner of the ring, wearing a dark purple robe, there was Battling Siki, the first African-born world boxing champion and already a flamboyant, controversial figure aged just 25. In the other, dressed in a white-grey robe, was Mike McTigue, a stonemason’s son from County Clare recently returned from an underwhelming boxing career in America. It was March 17 1923, Ireland was at war, and the boxers were about to go head-to-head in the fight of their lives.

The bell went and the St Patrick’s Day match at Dublin’s La Scala theatre began. The 20-round marathon would mark the beginning of the end for the Senegalese maverick and lead to a boxing rebirth for the 31-year-old Irishman. But that was only the half of it – for the newly constituted Irish Free State, the fight offered a chance to show the world that Ireland was back to normal despite the ongoing civil war. For the state’s enemies – the IRA forces who wanted full independence rather than dominion status – the match was a target, and the boxers pawns who might be eliminated to advance their cause.

Already, the IRA had issued death threats to Siki and McTigue and they had planted a bomb near La Scala, hoping to knock out the power to the theatre. But they blew up the wrong electricity cable and spectators soon forgot about the threats outside as the boxers laid into each other in a battle for the world light heavyweight title.

For a match between men who would not have been welcome in any other ring, the fight was a thriller; at one point, McTigue aimed a right-hander at Siki, who ducked; the Irishman dislocated his thumb on his opponent’s skull. Finally, after 20 rounds – it was the last 20-round world title fight – McTigue was declared the winner, paving the way for a triumphant return to the boxing rings of America.

For Siki, the outcome marked the start of a fatal drift into dissipation. Three years later, he was dead, shot three times in the small hours of the morning on a New York street. He was just 28.

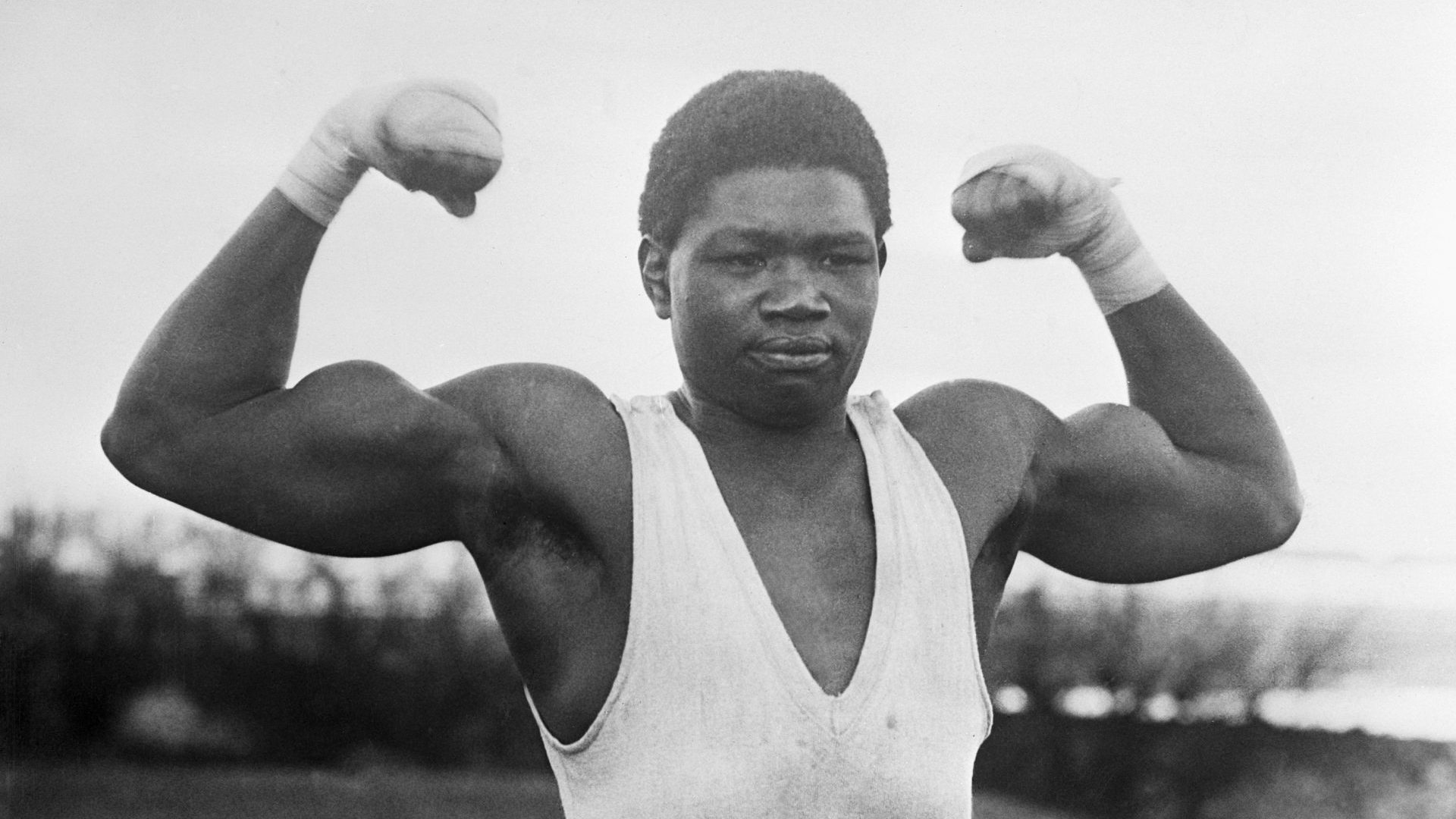

Battling Siki, or to give him his full name Louis M’Barick Fall, was born in 1897 in the port city of Saint-Louis in Senegal, then a French colony in west Africa. Nobody is quite sure how he ended up in France – one story has it that a Dutch tourist got talking to him during her ship’s stopover and brought him back with her; others say he was taken as a slave – but by his early teens, he was working in a restaurant in Marseille. Legend goes that a boxing promoter spotted him one day when he decked a difficult customer. He moved to the Netherlands, where he started training to be a fighter, earning the nickname Battling Siki.

His nascent boxing career was stymied by the outbreak of war, and he was conscripted into the Senegalese Tirailleurs (sharpshooters), a French army corps that included thousands of young men snatched from their homes and forced to fight for their colonial masters. Siki was decorated for bravery, winning the Croix de Guerre and the Medaille Militaire.

After the war, Siki was discharged and began boxing again in Amsterdam. Eventually, he secured a fight against the reigning world light heavyweight champion, France’s Georges Carpentier, a war hero and Hollywood film star who was somewhat out of shape, but determined to leave nothing to chance in his first fight on French soil for three years.

Siki was paid to throw the fight – essentially to play a bit part in the glorious return of the photogenic white hero. But in the custom-built stadium in the Paris suburb of Montrouge in front of around 50,000 spectators, including a young Ernest Hemingway, things did not go to plan.

Siki was no actor – although, ironically, he’d appear in a German film the next year – and Carpentier got annoyed at his obvious faking in the early bouts. He started whispering threats and insults and hitting harder, even though Siki had stipulated as part of their deal that the Frenchman was not allowed to seriously hurt him.

Eventually, Siki was provoked into fighting back, and downed the Frenchman in the sixth round. As he fell, Carpentier clutched his leg, claiming that Siki had tripped him. The referee disqualified the African and the crowd went wild: they wanted Siki to win. The fight’s judges overturned the ref’s ruling and Siki’s arm was raised in one of the biggest upsets of 20th-century boxing history. He was a new world champion, the first African to hold such a title.

The young fighter was not shy about flaunting his success. Afterwards, he paraded down the Champs-Élyées in a top hat and tuxedo, throwing money into the crowds. Footage shows him beaming and smoking a cigar. He became a legendary fixture in the Paris nightclubs and reportedly once hit the town with a pet lion cub on a leash.

But he was not given long to savour his victory. The French press were furious – how could a Black man dethrone a national icon and war hero? The racism was brutal, unflinching – Siki was dubbed “ugly as a toad” and a “monster”. Newspapers accused him of sleeping with underage girls and dealing cocaine. Countries including Britain refused to allow him entry, preventing him from having another fight.

Soon Siki was drinking more heavily, broke and desperate, a victim of vicious racism and perhaps his own hubris. Eventually, his decline and need for a purse – any purse – to get him back on his feet found an answer in Ireland, where a syndicate of sportsmen and business leaders were looking for a fight to put Ireland on the map after the formation of the Free State on December 6 1922, following a three-year war of independence.

Initially, Siki was not keen on fighting in Dublin – he didn’t rate McTigue, and didn’t want to travel to Ireland where the civil war was still raging. But his promoter persuaded him and he arrived in Cobh, County Cork, to be met by a big crowd of enthusiastic boxing fans. He took the train to Dublin and was reportedly very interested in seeing the damage caused by the civil war as he crossed the country.

In the capital, around 100 journalists had gathered to report on the big match, creating a massive headache for the Free State authorities, who until now had used censorship to control information about the effects of the war and the brutality of its fight against the IRA. They wanted visiting reporters to see Ireland at its best, but just a few days before the match, several IRA prisoners were executed, and in revenge the IRA decreed that no sporting events should take place as a mark of respect.

According to the 2008 Fastnet Films documentary Troid Fhuilteacht (A Bloody Canvas), McTigue received a letter on the morning of March 17 warning that he would be hanged if he went ahead with the match. Armoured cars were sent to pick him up from Lucan where he was staying and bring him to Dublin. Siki also received a military escort.

They made it to the capital, where the IRA bomb plot misfired, and the fight went ahead.

For the first few rounds, McTigue was on the defensive until one of Siki’s punches opened a cut over his eye. He decided it was time to try something new and started skipping around before delivering the heavy right hand that broke his thumb. But he kept going, and by the end of the 16th round it was clear Siki was tiring – he had to be pushed out of his corner for the 17th. The men fought on until the 20th round and then came the referee’s declaration that McTigue was the winner.

For Siki, it was the beginning of the end. Like McTigue, he moved to America, but after a string of losses he found himself punching his way through second-rate fights in and around Hell’s Kitchen in New York. He was drinking heavily, and regularly brawling, often fighting his way out of bars after refusing to pay his bill. He also married a white woman and often fell foul of the south’s segregation laws when travelling to matches.

On December 15 1925, as he was walking home after another bout of drinking, he was shot twice. He tried to continue on his way, crawling 40 feet before dying in the street. No one ever claimed the murder, but Siki had many enemies, and there were some who believed he was killed for refusing to throw a fight.

It was an ignoble end for a larger-than-life character, a man who spoke five languages, who was described as warm and witty and who had defied circumstance, colonialism and racism to rise to the top, only to be undone in a world ill-prepared for the kind of equality he represented.