What is our contemporary attitude to history? Do we have one? For some people, our history is a single rigid narrative, locked off and unchangeable, armour-plated against reinterpretation yet still apparently flimsy enough to be erased outright by some people pushing a cheap hollow effigy into a harbour.

For others it’s a more amorphous thing, constantly shifting with each new discovery via archaeologist’s trowel or archivist’s eureka, new light always being thrown on to old stories. For some it’s something we did at school that’s now a handy form of entertainment, from the sugar-coated portrayal of class hierarchies in an English stately home to a grinning Errol Flynn, arms akimbo in tights and a jerkin.

Perhaps the abiding sense we have of history is that it’s separate from us and our world, something to be visited at weekends with membership cards and little window stickers for the car park, passing along the edges of rooms behind ropes until we reach the gift shop where we can buy a jar of branded chutney and a fridge magnet to commemorate our brief encounter with the past.

I suspect we might even be guilty of believing that history ends with us, that our era is the status quo and, give or take the odd technical advance and change of government, how we live now is how it will be from now on.

This is a dangerous mindset, cocky and complacent. It’s the mindset of people who scoff when events like the whipping up and execution of the January 6 insurrection are called fascism, saying don’t be ridiculous, fascism is in the past, it died with the shouty guys in the black uniforms and shiny boots, this is just a bunch of angry folks letting off a bit of steam.

Even with a war on our continent and dramatic new evidence of climate change in the news almost daily there is still a sense that ours is essentially a time of equilibrium. Everything will be fine because we’re here now, the clever ones, the sensible ones. What did those people in the past know, capering around in ruffs treating serious illnesses with boiled leaves and incantations? Pfft, we’re far too smart to make THEIR mistakes.

As we forge ahead relentlessly here at the sharp end of time, this arrogance of the contemporary obfuscates how we are connected inextricably to the past. We’re the product of it, enmeshed in the stuff, our era simply the current incarnation of an ever-changing web of interconnected stories. A true awareness of the past should induce an enlightened humility, not the sense that we can haul up the ladder on what’s gone before because we know best. Maybe if we did accept our middling place in the chronicle of history the present wouldn’t be such a calamitous bin fire.

In Britain the past is discernible in the landscape. From the hillside terracing of medieval strip farms to the stunted ruins of castles to arrow-straight roads following their Roman predecessors, we don’t have to look far to see evidence of the past all around us. We live in history; we’re all part of history.

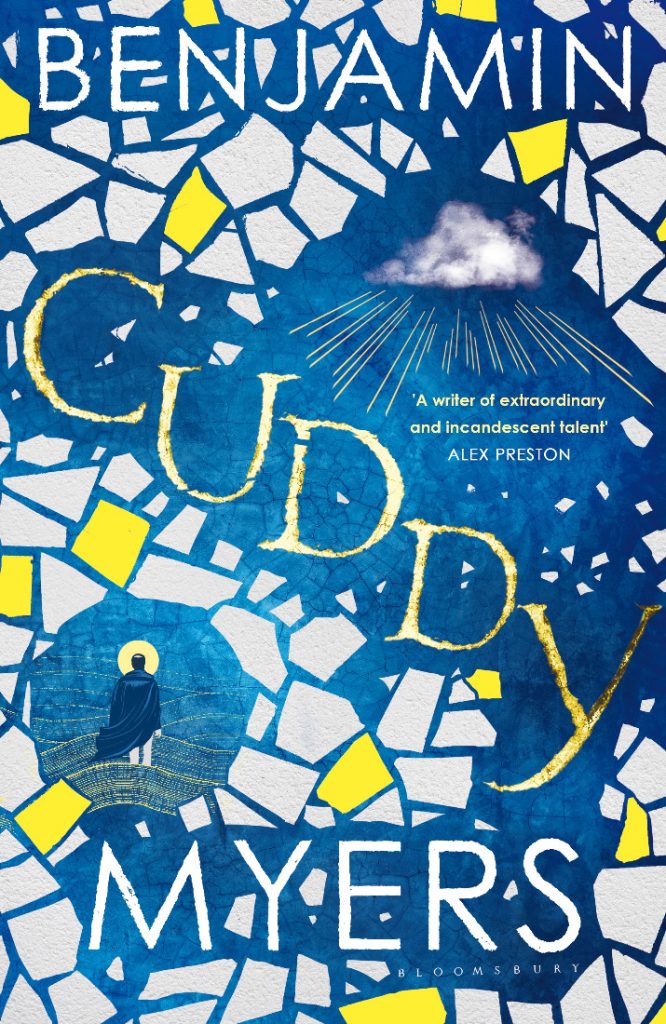

Few writers today express that sense better than Benjamin Myers. His 2017 novel The Gallows Pole, currently being adapted for the BBC by This Is England director Shane Meadows, won the Walter Scott Prize for historical fiction with its tale of a gang of 18th-century coin clippers in the Calder Valley, a story presented so evocatively the reader can almost smell the loamy land and the smoke of the charcoal burners drifting out of the trees.

Ambitious in his style, the prolific Myers works best when he has a range of voices to play with, imagining entire communities with their own rhythms, routines and stories. Last year brought The Perfect Golden Circle, following two vividly drawn characters through the Wiltshire summer of 1989 making crop circles and drawing out of the shadows a range of misfits and outsiders to create a frequently moving portrait of rural Britain in the late 20th century.

If 2019’s The Offing felt a little constricted by being a two-hander, recounting a summer after the second world war when a teenage boy goes on the tramp before returning to a future as a miner and strikes up an unlikely friendship with an elderly spinster living in a remote cottage on the Yorkshire coast, his new novel Cuddy sees Myers playing to his strengths and in his best form.

Cuddy is St Cuthbert, a seventh-century mystic most associated with the cradle of British Christianity at Lindisfarne where he was prior, before decamping to a hermitage on one of the remote Farne Islands to see out his final years.

His piety and selflessness led to Cuthbert becoming a posthumous inspiration to a cult of dedicated followers who carried his remains and the relics associated with him around the North East, staying one sandalled step ahead of Norse invaders right up until the turn of the first millennium. They settled at what’s now Durham, building the cathedral as a permanent resting place for Cuthbert’s bones.

The saint remains a significant figure in the lore of north-eastern England, religious and secular. Cuddy celebrates this, the man, his legacy and the cathedral itself employed as the narrative spine of an extraordinary polyphonic novel set over a thousand years.

Myers pulls us through a millennium of history, choosing his stopping points carefully in order that the story he wants to tell doesn’t feel rushed or disjointed, from the haliwerfolc, the “people of the holy man”, wandering the region with Cuthbert’s coffin to Michael, a contemporary teenager for whom the cathedral becomes a key focus of his challenging life.

The novel begins as poetry, an ambitious move that could backfire but succeeds by finding a resonance somewhere between the Old English of The Wanderer and Basil Bunting’s Briggflatts. The voice of the saint whispers behind the straggling handful of monks still carrying Cuddy’s remains at the turn of the first millennium, aided by a boy looking after the animals and Ediva, an orphan adopted by the itinerant band to cook for them.

Ediva also experiences visions apparently foreseeing the future cathedral itself, “made so ornate as to silence all who climb the hill to cast awestruck eyes upon windows that tell stories and shatter the day into stunning rainbows”.

More straightforward prose returns in the middle of the 14th century when Eda brews the finest ale in the district and sells it to the stonemasons working on expanding the cathedral. She’s married to the best longbowman for miles around who is also a vicious brute of a husband. When he departs to assist in putting down rebellious Scots, a fledgling romance develops with a mason named Francis Rolfe who woos her with eels and a deeply felt immersion in the lore of Cuddy and the cathedral in a finely wrought evocation of the medieval North East.

The year 1827 brings a pompous academic with a simmering dislike of the north of England to the opening of Cuthbert’s tomb to test a legend that declares the saint’s remains have never deteriorated. Professor Forbes Fawcett-Black’s snooty demeanour and a tangle with the supernatural sails close to an MR James pastiche but stays clear enough to evoke a genuine and significant event in the history of the cathedral.

The final and strongest section of the book takes place in 2019 and follows Michael Cuthbert, a 19-year-old from a village outside Durham scraping by doing short-term manual work and caring for his dying mother in a neat echo of Cuthbert’s last days as detailed at the start of the book. When he’s offered a job at the cathedral assisting stonemasons restoring one of the towers, Myers brings us to a thoroughly moving climax.

It’s hinted that Michael is descended from the earliest figures in the novel. He’s never been inside the cathedral before, but when he enters he finds “it feels both familiar and mysterious, as if a hundred past lives are nodding to one another in wordless acknowledgement, the endless echoes of his ancestors’ voices forever trapped in the stone”.

The cathedral and the saint at its heart awaken something within him, drawing out his innate goodness, giving him a sense of his place in the world and in the relentless flow of history to close this absorbingly beautiful book.

Myers spent five years on Cuddy and his immersion in the story and its people has produced a finely crafted and deeply moving novel. I can’t think of many writers as attuned to the present state of this country and the history and landscape that made it as Myers, who succeeds repeatedly in harnessing time with compassion, kindness and a rare gift for finding the right voice for the right people in the right era.

Cuddy confirms how we are not cut off from the past and that the conceit of our modernity must be pricked by the nuance and context of what has gone before.

Like Michael, Myers is aware that “he is part of history too, and that history is never-ending. He is one more link in a chain of people – of experience – that stretches deep into a past, a past where people spoke and ate and lived differently, but perhaps thought similar thoughts and desired similar things. A continuum, he thinks. Is that the right word here? We are all part of a continuum”.

Cuddy by Benjamin Myers is published by Bloomsbury Circus, price £20

A EUROPEAN LIBRARY

A weekly selection of fiction and non-fiction, new and old, to build a comprehensive literary portrait of our continent

77. THE NORSE MYTHS THAT SHAPE THE WAY WE THINK by Carolyne Larrington (Thames and Hudson, £20)

The myths and legends of the old Norse infuse much of our modern culture, from the Nazis skewing them for supremacist ends to Noggin the Nog via Tolkien and Game of Thrones. In this new study, Oxford academic Larrington takes 10 myths – from Yhhdrasill to Ragnar Rök – and explores their origins, tracing their subsequent journeys and examining their place in the culture of the modern world. Detailed, accessible and immensely enjoyable.