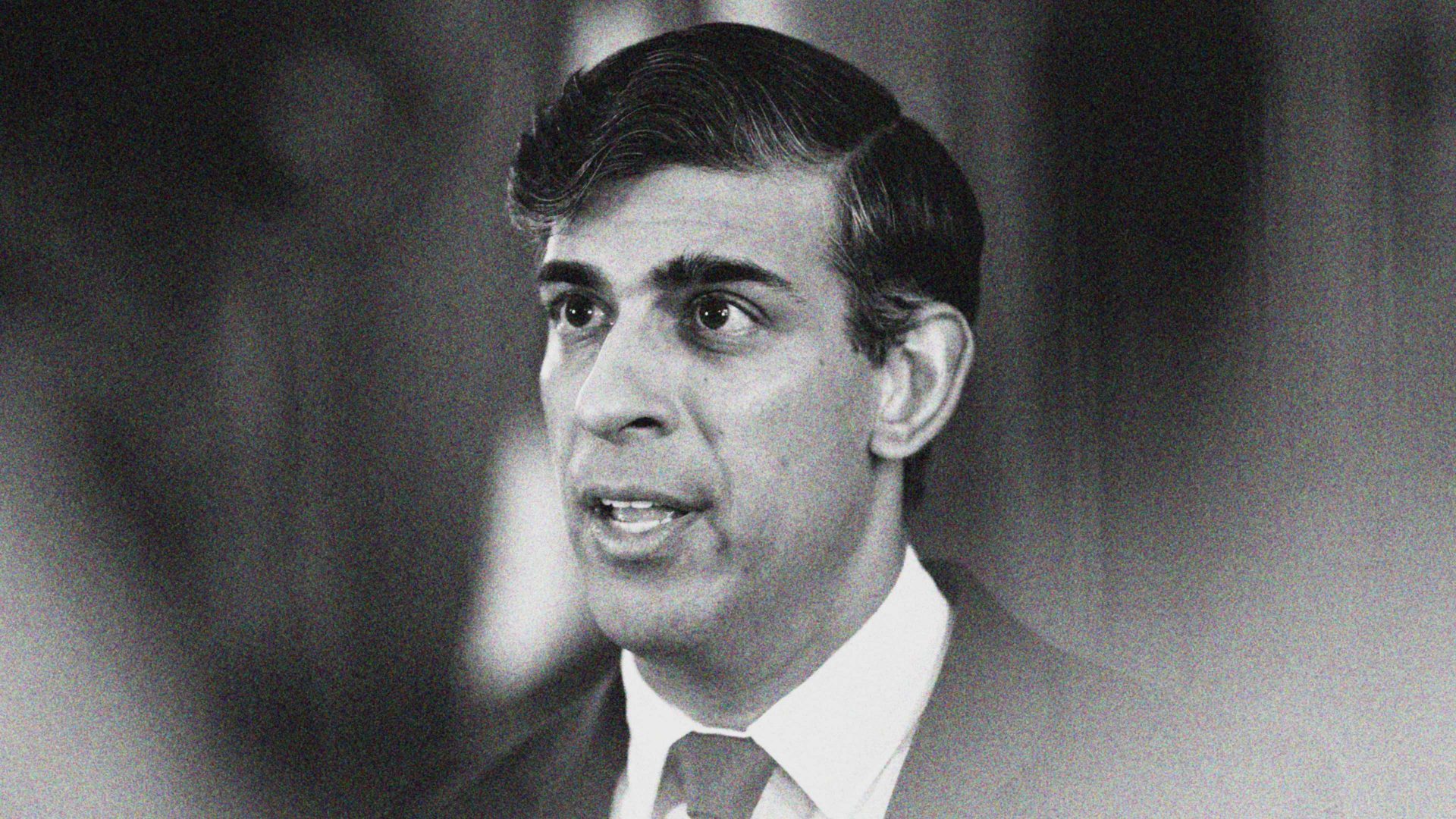

On the day Rishi Sunak made his “sicknote speech”, and set back the mental health cause a decade or so, my psychiatrist died.

I don’t blame the prime minister for David’s death, of which more later. But there did seem something especially disturbing about getting the awful news while watching Sunak’s latest attempt to signal political life, by suggesting that there was too much mental illness around, and the best way to deal with it was to let non-medical professionals take over from professionals in deciding whether someone was genuinely ill or not.

Of course, he dressed up his plans in terms of a “moral mission”, of work being the key to fulfilment and prosperity, and of fairness to people who do work and pay their taxes to help those who don’t.

But when he said, “I know – and you know – that you don’t get anything in life without hard work,” it wasn’t the image of a so-called welfare scrounger that popped into my mind, but one of Baroness Michelle Mone on her yacht, the Lady M.

Does Sunak feel the Covid VIP lane multimillionaires worked hard for their new homes and boats and Bentleys? Or whether they got them by just happening to be mates of ministers, or Tory donors?

And when he said that the biggest increase in the “economically inactive” was among the young, with depression and anxiety often cited as the reason, I wondered whether there was even a tiny part of him that asked whether any of the following might be factors:

The austerity under which they were educated, and which reduced child and adolescent mental health services to permanent crisis management; the Brexit that has taken a chunk out of the economy, and removed a ton of opportunities from a generation who didn’t vote for it; the double standards of the pandemic during which they were locked down while the country’s leaders lived it up; the housing crisis; the costs of education; the fact of being the first generation ever unable to say with confidence they will be better off than their parents.

It is doubtful he thought any of that. “Out of touch with the real world” doesn’t even get close. Give him a Tory mega-donor, and there is no limit to the empathy and patronage he can find; give him a Tory MP’s financial, sexual or indeed any other misconduct, and there is no limit to the tolerance and understanding of his fellow man. But show him a child living in poverty, or a single mum struggling to feed that child, or a homeless person living on the streets, and there is no limit to the performative cruelty and the rhetorical depths to which he will stoop to get a few tough guy headlines in the right wing rags.

Trying to blame foreigners crossing the Channel on small boats for the country’s ills doesn’t appear to have worked. They have decided they need a new othering target to drive their populist, polarising post-truth strategy… ill and disabled people, and all who try to help them.

It is desperate, desperate stuff. Sick, you might say.

So, to David Sturgeon, and a sad end to the life of a wonderful man. I have dedicated two of my books to David; my first novel, in which the hero was a psychiatrist, and my depression memoir, Living Better, in which he and all the help he gave me feature prominently.

I was introduced to him in 2005, when I was going through long periods of depression. In one awful bout I had been punching myself in the face, deciding as I did so that perhaps I needed professional help.

Over the next two decades, David became an absolute rock. Though there are a few reasons why my mental health is better than it was, he is one of the biggest.

He worked into his 70s, specialising in looking after students at University College London, until finally retiring last year. To celebrate retirement (though thankfully he had agreed to keep taking my calls whenever I was struggling) he and his wife, Liz, went away on holiday.

Not long after arriving in Yorkshire, he slipped and fell down a flight of stairs, broke his back, was rushed to intensive care – where he was later told he would never walk again.

He spent several weeks in intensive care in Leeds (treatment excellent, he told me), was then transferred to London for several months in hospital (ditto), before being moved to a care home. It wasn’t easy for him to absorb the notion that he would never live in his own home again.

But he settled in well. “This isn’t the future I imagined for us all, but it is a future,” was his wise, philosophical acceptance.

This is the man whose reply to my question, “What is the point of life, David?”, asked in a depressive phase, was this: “The point of life, Alastair, is to live it.” Wise advice.

A doting father and grandfather, who had helped so many people in his professional life, nobody deserved a long and happy retirement more than he did. It really is a tragedy that on the very day retirement began, his and his family’s lives were so horribly upended.

On my penultimate visit, I asked if there was anything I could bring “to brighten up the room a bit”. He said he would like two orchids.

So I took them on what would turn out to be the last time I saw him, and I will now never see an orchid without thinking of him, and never face a depressive episode without thanking him for the fact I am so much better at getting through them than I was before I met him.

Same day, more sad news, that former Burnley winger Leighton James had died, aged 71.

Much to the annoyance of my close friend Paul Fletcher, who thinks it should be him, whenever I’ve been asked to name my best-ever Burnley player I’ve always said Supertaff, as James was known to fans.

They say you should never meet your heroes, but I met Leighton many times, and loved his company. Such was my dedication as a teenager that I wrote and for a while managed to get sung a song about Supertaff, to the tune of Peter Sarstedt’s Where Do You Go To, My Lovely?

It went like this:

He was born in the back streets of Swansea,

Where millions of goals he did score.

But about football he knew nothing,

Until he came to Turf Moor …

Leighton James, Leighton James, Leighton James, Leighton James…

Oh, where do you go to, my Leighton,

When you’re alone on the wing?

Every time you dribble that ball,

My heart wants to break out and sing…

Leighton James, Leighton James, Leighton James, Leighton James.

My finest work! RIP David. RIP Taff.

“Richly deserved”, quote-tweeted Michael Gove above a tweet announcing that his former wife, Sarah Vine, had won a press award. What he perhaps failed to notice was that the article singled out in the announcement was headlined “Basket-case Britain is starting to feel like a Third World country where nothing works.”

A rare case of a Mail headline-writer clashing with the truth.