In the heart of Italy lies a collection of abstract art on such an enormous scale that it has a paradoxical effect: So reluctant was the 20th-century modernist Alberto Burri to part with 300 or so of his favourite works that he made elaborate plans in his lifetime for their conservation in his hometown. As a result, relatively few people are fully aware of the talent of Burri and of his many innovations, much imitated by other artists.

The Tate has one Burri, the National Galleries of Scotland two. More work is found across Italy, and in the United States, where he made his home for a while, including one piece so vast its creation influenced the choice of location of one of three Burri galleries, a disused tobacco-drying warehouse.

Tobacco is a major crop in the area around Città di Castello, Burri’s Umbrian birthplace in the upper Tiber valley. It can still be seen growing, its fat broad leaves yellowing in the autumn. Burri would have seen plenty of these in the country life he adopted, for a while living in a shepherd’s hut, shooting for the table.

This visceral life chimes with work that sprang unexpectedly from a man trained as a doctor and educated in the classics by his mother. A Montessori

teacher, she took matters into her own hands when his headteacher admitted he did not know the boy, who was a more enthusiastic footballer than scholar. A feeling for the countryside may have come from his father, a farm administrator.

Born in 1915, Burri was in the thick of the second world war as a young man, and it was his years in a prisoner-of-war camp in Hereford, Texas, that introduced him to poets, writers and creatives. He began to paint, but little remains of those early works except 50-odd exploratory pieces in which he developed his own visual language.

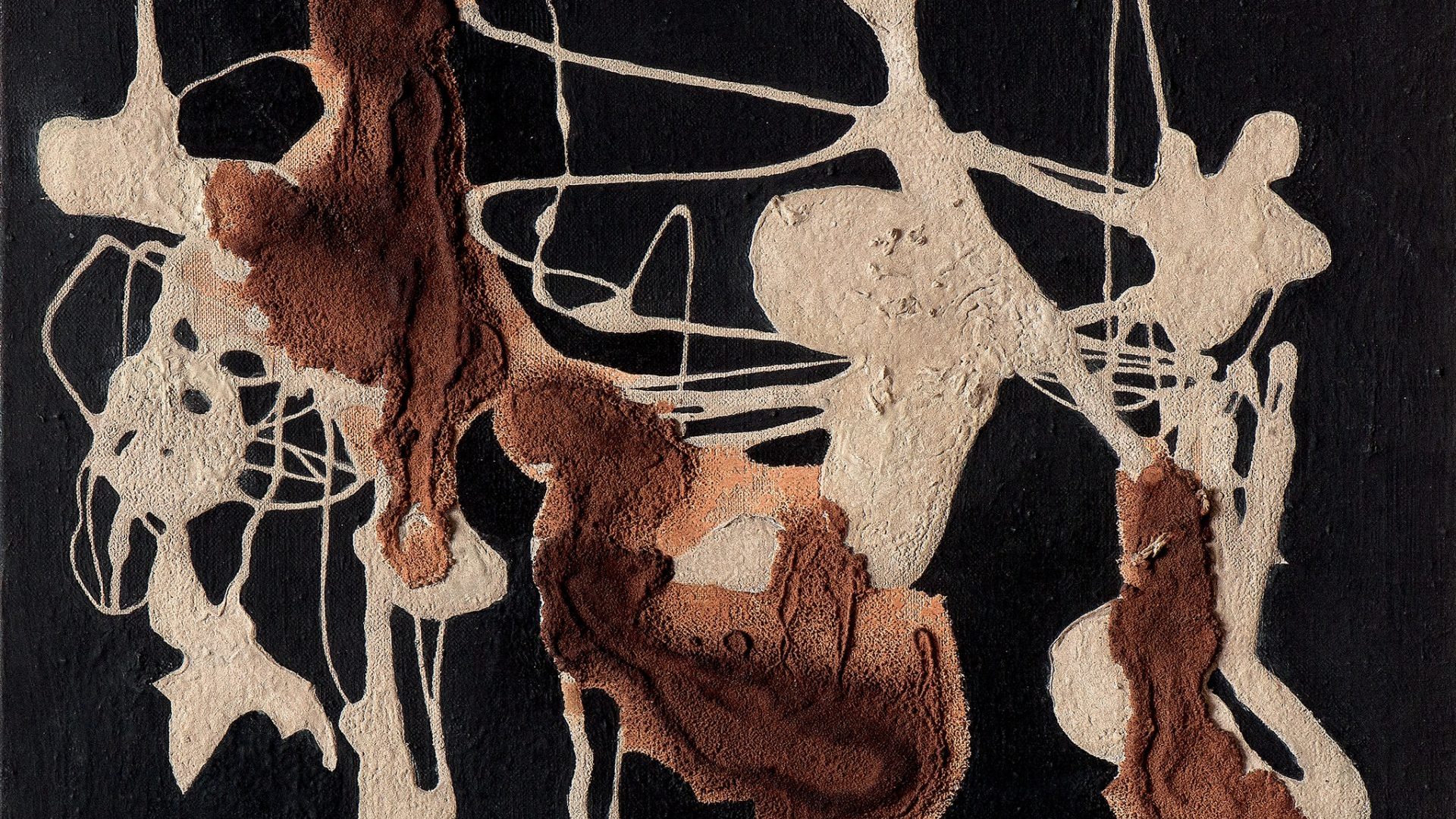

Newcomers to Burri are taken aback by his energy and scale of ambition. Industrial materials such as sacking, coated chipboard or plastic are ripped, sewn, burned, scored, peeled, poked and cracked. Early works in which crude suturing with coarse thread resembles surgical stitching prompted comparisons with his medical life. Confronted with this theory, Burri, no lover of critics, laughed off the idea. But it is hard not to see references to

the brutality of the war he knew in the blood reds, blackouts and cauterising

of frail matter.

It was within 20 years of his postwar reputation as an artist developing at impressive speed that he began to make plans to leave a huge body of work to Città di Castello. The little medieval city, still largely unchanged at its centre, is chiefly important in art terms as the place of Raphael’s first works after leaving his native Urbino. A few kilometres north in Monterchi is Piero della Francesca’s important fresco, the Madonna del Parto. The same artist’s Resurrection dominates nearby Sansepolcro. Giotto changed the course of art history down the road in the pilgrimage site of Assisi. Perugino, Luca Signorelli, Pomarancio and Raffaellino del Colle worked this lucrative patch, enriched by the wool trade, and by connections with the Medici. Burri’s art seems far removed from those painters of religious scenes. And yet, there is a directness in images which leap off the wall that ties in completely with his antecedents, and a passion akin to spirituality. In this, he resembles Rothko, and in another way, too: his works of art are vast.

Nothing prepares the newcomer to Burri for the volume of his work nor the scale. The artist alighted on the disused tobacco warehouse when he needed a huge area in which to work on a 15-metre piece for the University of California in Los Angeles. The warehouse had a track record in art: after the disastrous floods in Florence of 1966, millions of saturated documents and books were expertly dried out there. In 1989, to the shock of partners in his foundation, he bought it, on easy terms. It measures more than 100,000 square metres, and it needs all of that to show series upon series that explore independent ideas: the raw blast of red and black; the tactile stretches of bare sacking; the profundity of blacks differentiated by texture alone; sumptuous black and gold. Then, a surprise: joyous explosions in rainbow colours, in a cycle called Sestante. The long drying spaces with old mechanisms still hanging overhead accord each phase its own room. But after scores of works hung in this way, the story has hardly begun.

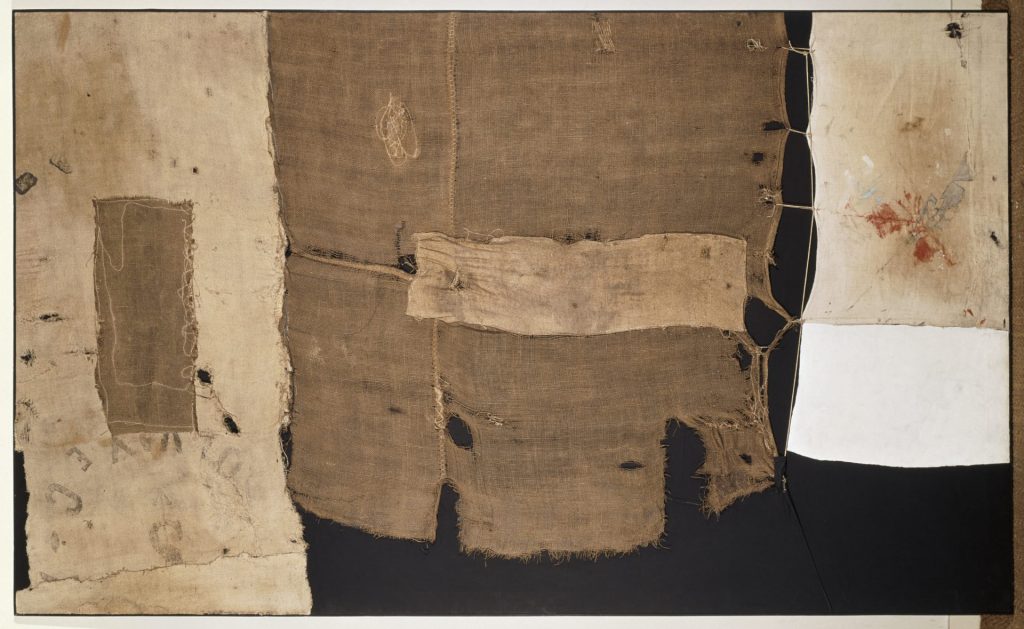

While the warehouse is on the outskirts of the town, a few minutes away inside the city walls, one of the town’s many palaces – the home of the Albizzini, who commissioned Raphael – houses another Burri gallery. Here,

complemented by Renaissance architecture restored partly at the artist’s own expense, are some earlier and smaller works, but also further series, including the colossal and distinctive Cellotex works. In these, taking boards of industrial film-coated chipboard, Burri pulls away some coating to reveal the coarse woody core, the contrast between matt and shiny surfaces alone defining firm geometric forms.

Rounding a corner, another shock: Burri has taken a flame to his work, melting and scorching smooth plastic, gouging out a wound. He may have

shrugged off associations with his medical past, but here that dissociation is hardest to believe.

In another series, the Cretti (craters), he again turns a negative force to positive. Drying out material, he allows deep cracks to open up, and these become the dark outlines of irregular forms that fill the picture space. It is this technique that underpins the Los Angeles piece.

Magnified, these cracks would become roads and intersections when Burri was commissioned to create a memorial for Gibellina, a town in Sicily destroyed by an earthquake in 1968. His response was to build on the vacated site – surviving residents being rehoused in a new settlement – a

shoulder-height labyrinth of channels and plateaus, undulating over the

hillside and entitled Il Grande Cretto.

A third gallery, in the basement of the warehouse, shows Burri’s many works on paper. There were theatre designs too, collaborations with the Città di Castello ceramics dynasty Baldelli, successes at the Venice Biennale, an

exhibition with the German installation artist Joseph Beuys, all of these

influencing other artists, including fellow Italian Lucio Fontana and the American Jasper Johns.

Burri died in 1995, but his legacy is still being revealed. Decades later, a large sculpture is waiting to be installed in a piazza near the gallery in the Palazzo Albizzini, and the Ex Seccatoi del Tabacco re-opened on March 12 – Burri’s birthday – after months of renovations. More and more of us can now witness the secrets and innovations of Alberto Burri, a truly great 20th-century artist who, in micromanaging the future of his own work, slipped through the net.