Pictures of Chinese nationals being held as prisoners of war in Ukraine have raised questions about the extent of China’s support to Russia. A Chinese foreign ministry spokesman has stated that China is “a staunch supporter and active promoter of the peaceful resolution of the crisis”, and suggested that Chinese soldiers fighting for Russia were doing so in their private capacity. President Zelensky claims there are at least 155 Chinese citizens doing so. It is not common for Chinese nationals to take such potentially embarrassing action without official approval.

There is one group of people, however, who will have welcomed the pictures: the soldier’s families. They have the comfort that their loved ones are safe and will be treated according to the Geneva Convention. But the loved ones of tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians do not have that comfort. American negotiations to end the war in Ukraine have so far focused on land and security guarantees. The prisoners should be a reminder that the fate of people affected by this war should be the immediate priority of the negotiations.

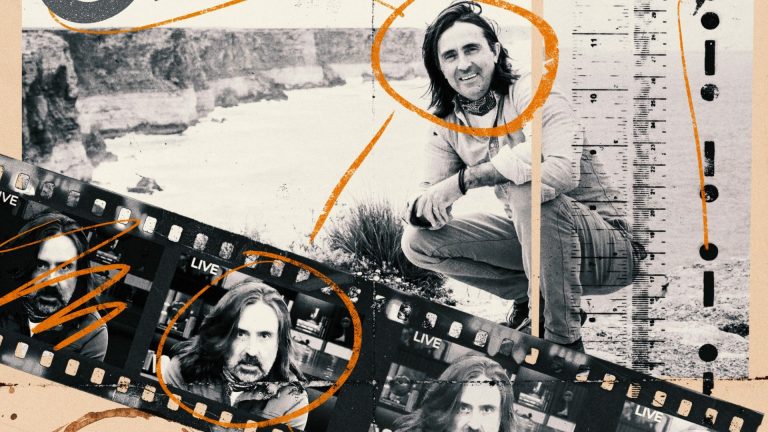

In 2019, the Ukrainian photojournalist Zoya Shu began photographing people freed from Russian detention. She has spent time with many former PoWs, listening to the distressing stories of their time in Russian prisons. I met Shu in London, where she told me about Olexiy Anulia who was so hungry he ate worms and a live rat to survive (the rat tasted like liver). She told me of the cold water punishments that led to prisoners losing fingers and toes and showed me the photos of the remaining stumps. She described the beatings and the electrocutions, and how some were kept in cages. She described the forced singing of the Russian national anthem as part of systematic attempts to destroy their Ukrainian identity as well as break them down physically and mentally.

Shaun Pinner, a former British soldier who joined the Ukrainian army to fight for his adopted home after settling there and marrying a Ukrainian, was captured by Russia during the siege of Maripol. The description of the early days of his capture is indistinguishable from the experiences of those held by terrorist group Isis, and corroborates the stories Shu was told.

At one point men in balaclavas draped a Ukrainian flag around his shoulders in front of a camera on a tripod. He was convinced that, “This is going to be filmed and my death will be used as propaganda”. Pinner experienced a mock execution and heard stories of other receiving the same psychological torture. Pinner described hearing the brutal beating that British aid worker Paul Urey was given by prison guards two days before he died. When Urey’s body was released, Ukraine’s foreign minister, claimed an examination showed “signs of possible unspeakable torture”.

The findings of a UN Commission of Inquiry reveal that the experiences of Pinner and those that Shu photographed are not anomalies. It concluded that Russia’s use of torture against prisoners and civilian detainees amounts to crimes against humanity. The report outlines how Russian forces have subjected Ukrainian captives to brutal beatings, burns and electric shocks amplified by water. It also details how Ukrainians are forced to endure sexual violence, including rape.

The deputy head of the United Kingdom delegation to the organisation for security and co-operation in Europe, Deirdre Brown, has stated that, “The UK unequivocally condemns the Russian state’s reported systematic torture, abuse, and execution of Ukrainian prisoners of war”. Her organisation has concluded that the torture of captured soldiers and civilians by the Russian state is widespread and systematic. Additionally, the Ukrainian prosecutor-general’s office reports that 147 Ukrainian prisoners of war have been executed by Russian forces since the start of the full-scale invasion.

Among all this physical pain, there is a unique psychological pain, inflicted by Russia. A therapist told Shu that, “Out of all the different cases of traumatised frontline soldiers, ex-prisoners of war, and others impacted by the war, working with the relatives of missing soldiers and civilians is the hardest”. For many who have disappeared into the Russian prison system their loved ones still have no idea if they are alive or dead.

In some ways this is a worse outcome for their families than receiving confirmation of their death. The US psychologist Pauline Boss, who started working with the wives of missing US airmen in the 1970s, writes that “even sure knowledge of death is more welcome than a continuation of doubt”, and describes incomplete or uncertain loss as “ambiguous loss”.

This is a unique form of psychological torture that keeps the wound open. The rituals of closure and resolution are denied. This is why some states and armed groups deliberately “disappear” those who are seen as their greatest threat. During the Troubles in Northern Ireland, people suspected of informing on the IRA were at risk of vanishing.

Mass communication makes the idea of not knowing what’s happened to a loved one seem unthinkable. We are used to having the answers at our fingertips, search engines take us to forgotten facts, and clouds hold images of millions of misremembered memories. Yet, this is the daily reality for those living in the occupied territories of Ukraine and for those families who have loved ones at the front line.

When humans tell stories, we place a great emphasis on the ending. We make sense of our lifespan with fictional stories that have an origin, a middle and an end. This simple sequence puts our mind at rest. Stories have always helped make sense of our world, and of the tragedies that occur within it. These stories have a universal grammar. If the end of your story is not known, this universal grammar is not followed.

in Donetsk in 2014. Image: Zoya Shu

A distressed fellow detainee, Dimitri, told Pinner, “I don’t think I’m ever going to get out… All the people I love… They don’t even know I’m here. They have probably written me off as dead. My poor mother…” Pinner and the detainees in his cell memorised each other’s phone numbers, so that if one was released they could call the others’ loved ones. One of the first calls Pinner made on release was to Dimitri’s mother.

In March, Russia and Ukraine exchanged 175 prisoners each, following a phone call between Trump and Putin in which the swap was discussed. Russia handed over an additional 22 seriously wounded Ukrainian prisoners. While this should be welcomed, there are tens of thousands of prisoners still being held. The Ukrainian government is working to track these POWs. I ask Shu what can be done to support this work.

“We need the international community to help secure independent monitoring of Russian prisons and detention facilities in the occupied territories,” she said. The aim would be to “create pressure on Russia to improve the conditions of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilian hostages, and to help ensure their prompt and safe release.

“Since the Red Cross is currently not fulfilling its monitoring role, other neutral international organisations or independent representatives – possibly even involving relatives of the prisoners – must be granted access, to assess the conditions of Ukrainians in captivity, in accordance with established international law.”

The international community should also push for Russia to notify the loved ones of all those it has in its prisons. This should include the locations of the approximately 35,000 Ukrainian children kidnapped by Russia. Efforts to track the location of these children have been hindered by the US’s recent defunding of a research unit that helped locate them based at Yale University.

The forcible abduction and deportation of children is a war crime under the statutes of the International Criminal Court. It may also be considered genocide if the aim is to eradicate a particular ethnic, racial, or religious group.

Currently, 6000 women are missing, 400 are confirmed to be in captivity. Many are in sexual and labour slavery. Some of the released women mention that they were injected with an unknown substance. Image: Zoya Shu

There is little chance that any of those Russians identified as part of the state’s torture apparatus will be brought to justice under Putin’s leadership. This should not stop the collection of evidence. They should know that the cases against them will be kept open as long as they remain alive. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian special forces are using similar tactics used by Mossad against Nazi war criminals by seeking to track down those responsible outside their own borders.

One morning, an attaché from the Ukrainian Embassy texted Pinner a newspaper article about a targeted attack against a Russian judge. It was the judge responsible for giving Pinner a death sentence in a sham trial. Pinner replied suggesting this was karma. Yes, karma, said the attaché, “And the Ukrainian special forces”.

Trump has rightly demanded the return of Israeli hostages held by Hamas, and should be applauded for his role in helping push through the March exchange. He should be as vocal in calls for Russia to return those it has taken and subjected to widespread and systematic torture. That torture, mental and physical, is still happening now. There are thousands of families that are suffering the ambiguous loss of not knowing whether their loved ones are alive or dead. There are thousands suffering the unique psychological torture of not being able to tell their loved ones they are alive.

The Russian writer, Fyodor Dostoevsky, who was sent to a prison in Siberia claimed, “A society should be judged not by how it treats its outstanding citizens but by how it treats its criminals.” Russia sends its own prisoners to die in the meat grinder that the frontlines in Ukraine have become. If Russian society were to be judged on how it treats its prisoners of war, the judgement can only be the harshest.

All images credited to Zoya Shu