On September 18 1961, a Transair Sweden flight bound for Ndola in former Northern Rhodesia, modern Zambia, crashed shortly before landing, killing all 16 on board. Among the dead was the secretary-general of the United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld, on his way to broker a ceasefire in the Congo. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize posthumously, the only person to be so honoured, and his untimely death was the source of universal regret.

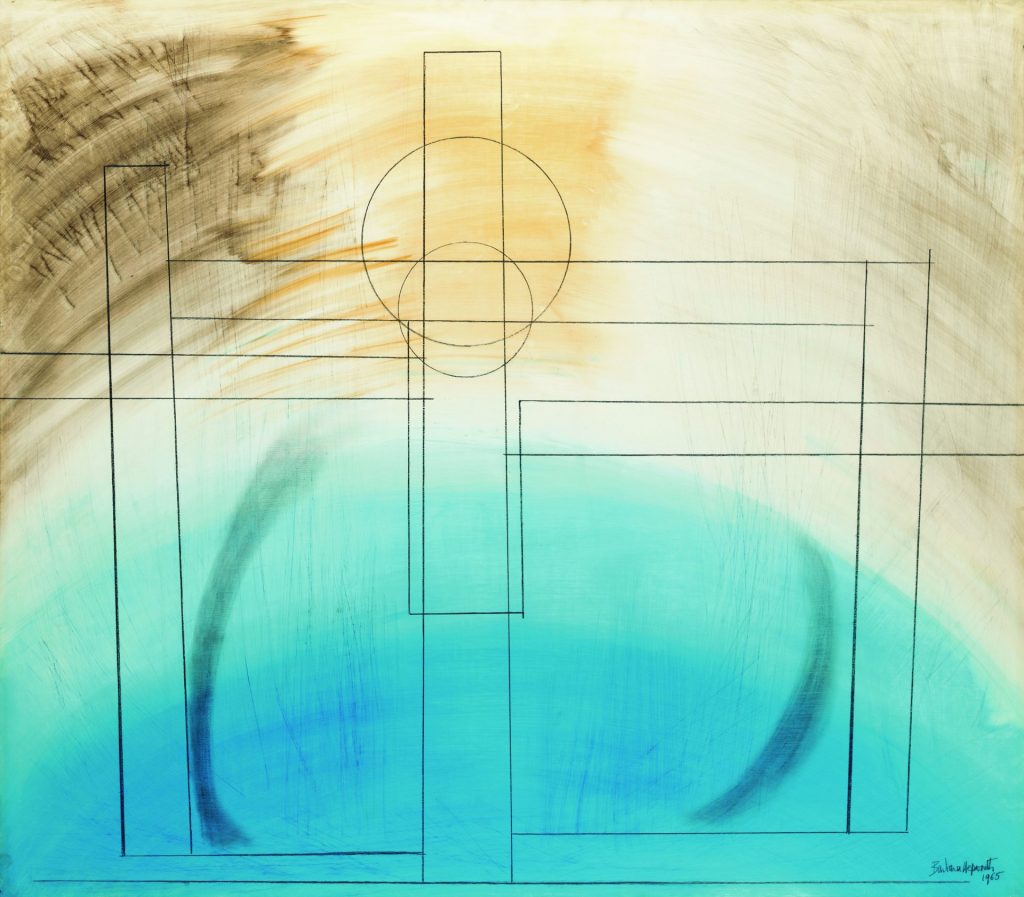

For the artist Barbara Hepworth, the loss was felt on two levels. She was both an ardent internationalist who believed passionately in the peaceful values that Hammarskjöld and the UN upheld, and a personal acquaintance. The statesman had an early piece by Hepworth in his office at the UN, and

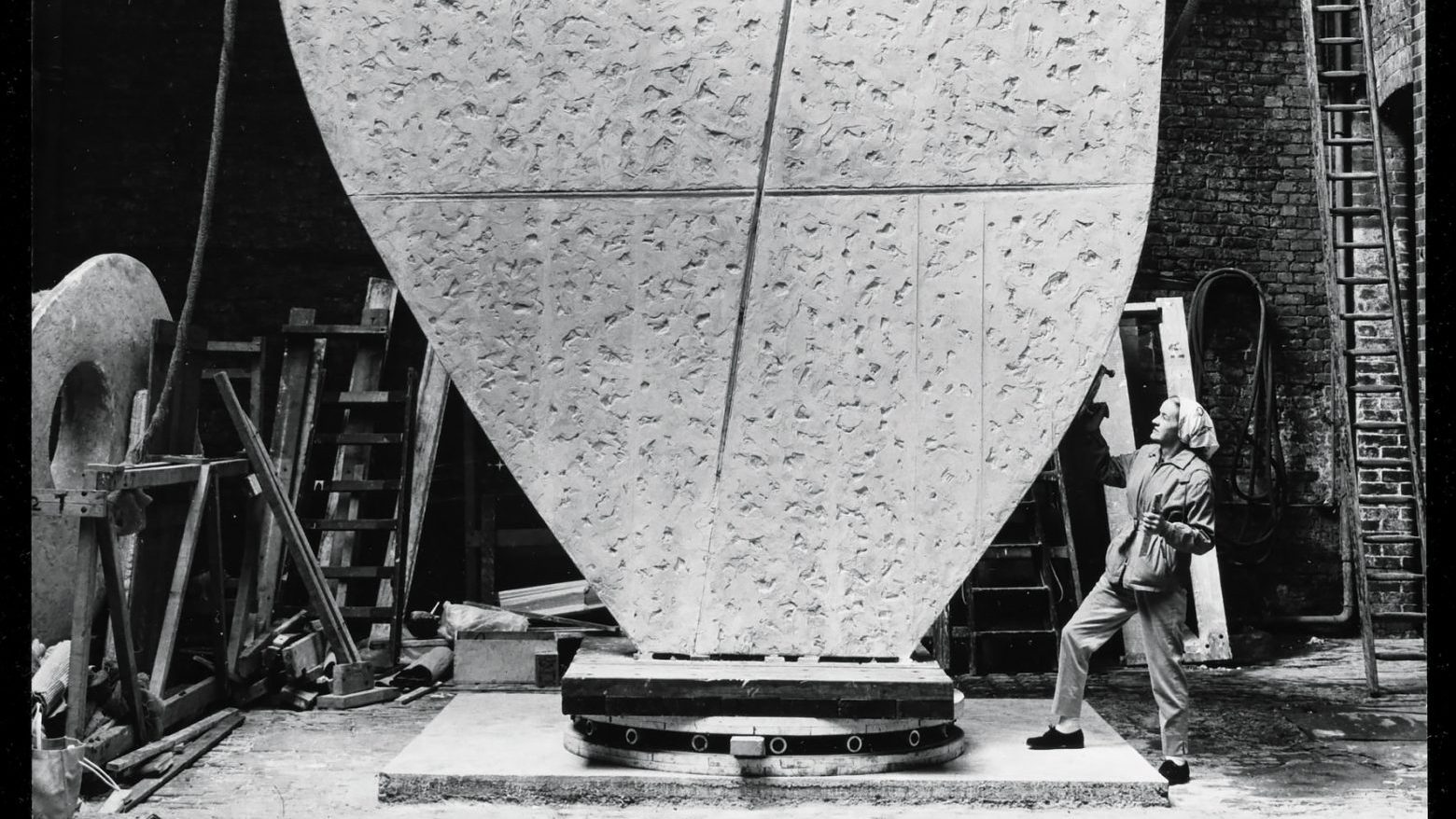

discussions had begun about her creating a large work for the UN. In the

event, the 6.4 metre-tall sculpture that emerged three years later, Single Form, became not only a symbol of an undivided world, but also a memorial

to Hammarskjöld.

The story is told at Tate St Ives in Barbara Hepworth: Art and Life, an exhibition about the sculptor before and during her years in Cornwall. Here, from the outbreak of war, she made her home – as a skylit studio in north London was not an ideal place in which to raise four children when bombing began.

But although it is with the Cornish town that Hepworth is most associated, her intense relationship with the landscape had begun in her childhood. “All my early memories are of shapes and textures,” she wrote in 1970. “Moving through and over the West Riding landscape with my father in his car, the hills were sculptures, the roads define the form.” Herbert Hepworth was a civil engineer; his wife, Gertrude, known as Gerda, was good with her hands, making her own clothes. The scale of vision of one and the practicality of the other were perfectly combined in their daughter, named Jocelyn but known as Barbara.

A brilliant student at the Leeds School of Art and Royal College of Art, she nonetheless missed out on a scholarship to Rome that went to another promising youngster, John Skeaping. Still desperate to study in Italy, she managed to land local authority funding for a stay in Florence.

Here the two young artists met – and married in short order, in 1925. They

also discovered, in the land of Michelangelo, Bernini and Canova, the physicality and expressiveness of direct carving. Visiting the marble quarries of Carrara, north of Pisa, and absorbing the work of Renaissance artists, the Yorkshirewoman found her self-devised travels literally illuminating. “Italy,” she wrote, “opened for me the wonderful realm of light – light which transforms and reveals, which intensifies the subtleties of form and contour and colour – and which imparts a richness and gaiety into the living material of stone and marble.”

Hepworth returned to Britain with a changed outlook. With Skeaping she staged a joint show that was critically well received but little visited. After

the birth of their baby, Paul, singular forms gave way to mother-and-child

embraces resonant of Renaissance religious art. And as the impetuous marriage to Skeaping faltered, her new relationship with fellow artist Ben

Nicholson led to a return to mainland Europe, this time as an artist of

increasing note.

In the vibrant melting pot of 1930s Paris they met, among others, the Spanish-born Pablo Picasso, the Romanian-born Constantin Brancusi, the Swiss-born Sophie Taeuber-Arp with her German-born husband Jean Arp, and the French-born Cubist Georges Braque. The couple were at the heart of a group of international avant-garde artists.

They brought back to Britain European modernist ideas – Nicholson astonished friends by painting a whole room pure white and thrusting up

high, for effect, a cork table mat painted red. And they brought back living modernists too. Nicholson and his first wife Winifred were instrumental in shepherding Piet Mondrian out of an increasingly volatile Europe, and with the move to Cornwall, Hepworth was joined in a friend’s household by the constructivist artist Naum Gabo. Encouraged by Gabo, she shared his fascination with the literal and metaphorical tension of strings, which she arranged across cavities in her work, making a sculptural space out of thin air.

While refuge in Cornwall brought relief from the London bombing, it came with shortages and the demands of feeding many mouths on thin pickings. She would write of ingenious housekeeping ruses to keep the family going during times of hardship, while following the progress of the war with alarm.

While her image may be of a singular artist who kept her assistants out of the limelight, she had a strong belief in community, and found being in a tight-knit town an important springboard for her work. A war effort plan to disguise the power station at nearby Hale with camouflage paint did not get off the ground, but was illustrative of a protective impulse.

In 1943 she bought a house in Carbis Bay, just outside St Ives. International

as she was in her outlook, she would perhaps have been astonished to know

that in 2021 the leaders of the G7 countries would converge on Carbis Bay, her old stamping ground, to discuss issues that concerned her in her own time, including ecology.

The war over, she bought the stables of her assistant John Milne’s Trewyn

House to create a studio and garden, and later acquired the Palais de Danse

opposite. Now under structural work and conservation, that spacious

building is earmarked as an extension of the St Ives displays and will eventually hold examples of Hepworth’s work. But the place will also revive the little-discussed link between Hepworth and the worlds of music and dance.

Sculptures that allude to dance, with titles such as Galliard and Pavan, miraculously defy their solidity with flowing movement and embody Hepworth’s belief that natural materials were living things. Music is similarly celebrated, in titles and allusions, the stringed forms suggestive of lyres or the Aeolian harp. In St Ives, she befriended the South African-born composer (Ivy) Priaulx Rainier, whose music is little heard today, even though her works were premiered by the leading mid-century performers, including the tenor Peter Pears, cellist Jacqueline du Pre, violinist Yehudi

Menuhin, clarinetist Thea King and oboeist Janet Craxton. Not universally

understood, Rainier opined that only architects and sculptors appreciated

her music.

She certainly got through to Hepworth, and as a keen gardener would advise her on the planting that, now mature, is enjoyed by visitors today. Invited to the studio in 1950, Rainier introduced the sculptor to Stravinsky’s treatise the Poetics of Music. Hepworth recorded that the “chapter on composition corresponds so exactly to the creation of form that a mere half a dozen words would need to be changed to make it a statement on sculpture”.

In 1953 Rainier, her fellow composer Michael Tippett and Hepworth founded what they intended to be an annual arts event, the St Ives September Festival, with artists including Pears and the counter-tenor Alfred Deller. The one and only event celebrated, with the accession of Queen Elizabeth II, the music and artists of two Elizabethan ages, but the project proved unsustainable in ensuing years.

In 1955, however, Hepworth designed the costumes, flats and props for the premiere of Tippett’s opera, A Midsummer Marriage. At the Palais de Danse, Hepworth was able to work on a colossal scale. To this day, debris from the plaster armature for the UN Single Form coats the flooring, which is in temporary storage while the building is made structurally safe for its return to public use. Working on the horizontal, Hepworth designed her sculpture to be made in six sections. It was here too that she worked on the Winged Figure that to this day hovers over John Lewis in London’s Oxford Street.

At the unveiling of what became a memorial to Hammarskjöld in 1964, in

her short speech Hepworth articulated her belief in the synthesis of creativity and thought. “Dag Hammarskjöld had a pure and exact perception of aesthetic principles, as exact as it was over ethical and more principles. I

believe they were, to him, one and the same thing. Literature, music, the

visual arts, and nature were both his recreation and an important and sustaining part of his routine…

“The United Nations is our conscience. If it succeeds it is our success. If it fails it is our failure.”

Like her Swedish friend, Hepworth died in shocking circumstances, when

fire broke out in her studio home on May 20 1975. Hepworth did not live to

see big strides in nuclear disarmament – or the rise in populism and culture

wars. But she had warned against warmongers and philistines in her copious writing.

“I feel that the time has come to protest against the immorality of present power politics,” she wrote in her big, fast hand. “Culture means the affirmation of life. There cannot be any culture whilst we make stockpiles of

nuclear weapons… What is morally right can only benefit mankind if we ask

these governments, in the name of art and literature and science to halt the

contamination of man’s spiritual growth.”

Barbara Hepworth: Life and Art is at Tate St Ives until May 1 2023