She was only 11; the wrong girl in the wrong place at the wrong time. On January 9 this year, in the Antwerp neighbourhood of Merksem, bullets tore through a garage door into the kitchen, killing her. Her name was Firdaous. She was the niece of one of Belgium’s main suspected drug traffickers, Othman El B, who is currently thought to live in Dubai.

The port of Antwerp topped the EU’s list of cocaine seizures in 2022, and the shooting of a young child has sparked outrage across Belgian society – and also alarm. Belgium’s northern neighbour, the Netherlands, has come close to becoming a narco-state. The worry is that Belgium is heading the same way.

Merksem is not far from the sprawling port of Antwerp, one of Europe’s busiest and, in terms of surface area, the biggest. It is divided from the steely grey waters of the river Scheldt by train tracks and the main highway leading to the Netherlands. Its main shopping drag is called Bredabaan, after the nearby Dutch border town of Breda. The Dutch connection in Antwerp is omnipresent, at least in the drugs trade, experts say. The current spate of violence, they aver, is in large part an overspill from the drugs scene in the Netherlands and comes as Antwerp is extending its lead as the cocaine hub for Europe over the Dutch port of Rotterdam.

“If you look at a map of Europe and the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp, in between you just have a small piece of grass, so it’s not unthinkable that many of the criminal groups in Rotterdam are switching to Antwerp. We’re pretty sure similar groups are involved,” says Tim Surmont, a Belgian analyst at the European drugs monitoring centre EMCDDA.

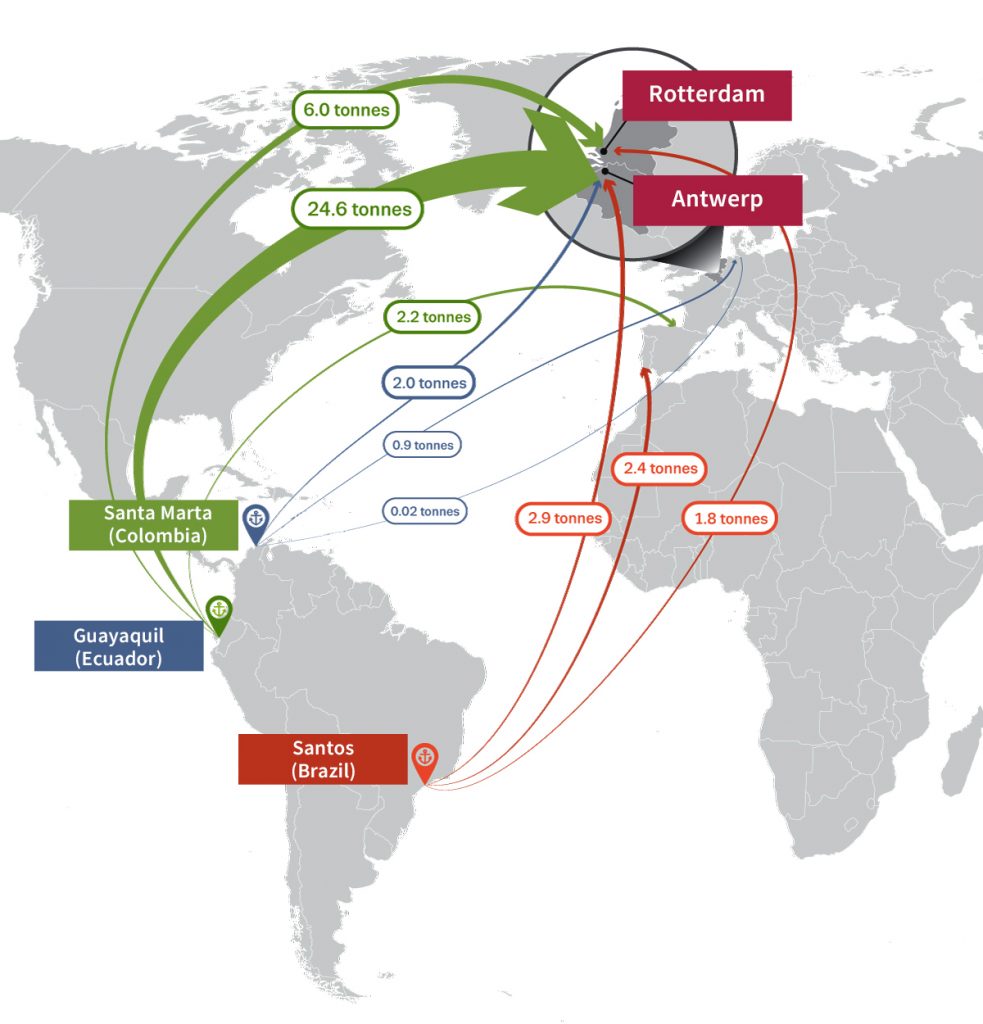

In early January, Dutch and Belgian authorities jointly announced annual drug seizures for the first time as the balance continued tipping towards Antwerp. Cocaine seizures in the Belgian port rose sharply to 109.9 tonnes in 2022, from 89.5 tonnes the year before. Rotterdam saw the reverse, with seizures going down to 46.8 tonnes from 72.8 in 2021. While some of this may be due to the increased efficiency of Antwerp customs and police, it does reflect the port’s primacy in the European cocaine trade.

For years, drug gangs have meted out violence on the streets of Antwerp, using mostly grenades, fireworks bombs and occasional shootings to intimidate each other and perhaps errant port workers reluctant to follow their orders. But this was rarely lethal and mostly regarded as grandstanding by the various rival groups. Even now, the death of Firdaous is seen by those in the know as unintentional, and in general, the number of drug trafficking-related murders in Belgium remains much lower than in the Netherlands.

Yet there has definitely been an uptick in drugs-related violence as Belgian criminal groups expand and become more independent from the Dutch networks they once mostly sub-contracted for. There are also growing similarities between the Dutch and Belgian situations: last year, police thwarted a planned kidnapping of Belgium’s justice minister, Vincent van Quickenborne. So far, five Dutch citizens have been arrested for the plot, but the minister and his family are still being kept at a safe house. In the Netherlands, the former minister of justice, Ferdinand Grapperhaus, is also under increased police protection because of a threat, thought to come from a major cocaine trafficker.

It’s another indication of the close connections between the criminal groups in Belgium and the Netherlands. “There’s definitely an overlap. I’m not saying there are no Belgian criminal groups, but there are certainly overlaps with Dutch crime groups,” says Surmont of the EMCDDA.

Belgium’s fragmented political and therefore governance structure, with the main dividing lines not only between the French and Flemish-speaking parts but also between the regional and the federal governments, might have contributed to an initially somewhat slow response to the drugs issue. The Flemish nationalist and tough-on-crime mayor of Antwerp, Bart de Wever, has for years harangued the federal government for more resources.

Teun Voeten, a Dutch cultural anthropologist and journalist specialised in the drugs trade, is based in Antwerp and in 2020 published a book on his adopted city: Drugs – Antwerp in the Grip of Dutch Crime Syndicates. He sympathises with De Wever’s predicament. “The mayor of Antwerp, Bart de Wever, he’s quite hardline on this and he feels abandoned by the federal authorities. He’s growing a bit tired of his city now being labelled as the narco-centre of Europe.”

The title of his book makes clear where Voeten lays the blame for Antwerp’s drug problems. He has no compunction about calling out his native country, the Netherlands. “I did my PhD on drug violence in Mexico and you see there that Mexico is a narco-state but not a failed state.

“In the Netherlands, you can see that there’s a large drugs economy that is part of the regular economy, so drug money trickles into the economy, and there is extreme violence, corruption and infiltration. Most people just look at extreme violence, while that is not essential for the drug cartels. But taking all that into account, the Netherlands scores high on the scale for a narco-state. I’d call it a functional narco-state, a narco-state light.”

Belgium, he says, can even now not be compared to the Dutch situation. The level of violence is still much lower, as is the manner in which it takes place. Liquidations are not uncommon in the Dutch drugs scene, with both gruesome (a beheading, for example) and high-profile cases. Among the latter are the murder of journalist Peter R de Vries in Amsterdam last year, as well as the assassination of the lawyer of one of the witnesses in a major drugs case in 2019.

Even so, many experts demur when asked about the narco-state characterisation, both for the Netherlands and Belgium. “There is no reason to speak of a narco-state, either in relation to the Netherlands or Belgium,” says Letizia Paoli, an organised crime expert at Belgium’s KU Leuven University who was a consultant for the Italian authorities at the start of her career.

The number of drug-related murders in the Netherlands, even though a much smaller country, was never on a par with places such as Mexico and has actually declined over the past decade, while in Belgium they’ve been relatively rare. Paoli also points out that another characteristic of narco-states is the infiltration of both government and law-enforcement.

“Both in Belgium and the Netherlands, there have so far been no cases of high-level politicians or law-enforcement officials who have been suspected of having ties with drug traffickers and so far, even the cases of low-level infiltrations have been really rare,” she says.

This is something that Tim Surmont of the EMCDDA also stresses: “There are criminal groups active, there is violence but that doesn’t mean that there’s a narco-state. I’m still convinced that at a political level in Europe political mandates are still clean of narco-criminals.”

Europe as a whole is facing an enormous increase in cocaine trafficking, he observes. The ports of Antwerp and Rotterdam are naturally attractive because of the central locations but they’re not the only ones that have seen an increase, partly brought about by increased production, mainly in Colombia. “In general, it’s increasing also in other ports in Europe, it’s just more pronounced now in Antwerp. You see ports like Le Havre, Algeciras, Hamburg, are also getting an increase in seizures.” Europeans, and especially Belgians, only consume a fraction of what is trafficked, and most drugs continue on elsewhere.

To tackle the drugs issue is no easy task without resorting to control measures that are more suitable to totalitarian states, say the experts. Voeten is encouraged that the Belgian federal government is now taking the problem more seriously, especially after the threat to the justice minister. He also commends Antwerp’s De Wever and his Rotterdam colleague Aboutaleb for acting proactively: “They’re also working on upstream disruption. Mayor de Wever and his colleague Ahmed Aboutaleb of Rotterdam have been twice to Colombia to talk to the authorities there. Consumers are also being discouraged, so a lot is happening on many levels.”

There is no law enforcement-only solution to the drugs trade, says KU Leuven’s Paoli: “For democratic states that want to maintain free trade, I think there are no really effective measures to control the drug-trafficking flows.” But there are ways of fighting criminal gangs. On the one hand, she is encouraged by the Italian experience. On the other she warns this cannot be translated directly to the Dutch and Belgian situations.

“I think that the Italian authorities have had tremendous success, especially against the Cosa Nostra,” says Paoli. “The Cosa Nostra is much weaker than 30 years ago, it’s really a shadow of its former self. On the other hand, I think that it was perhaps paradoxically easier to control the mafia, a well-defined criminal organisation, than it is to control drug trafficking. I don’t think that with law enforcement alone we can control drug trafficking.”

Ferry Biedermann is a journalist based in Amsterdam writing on Europe, the Netherlands and Brexit