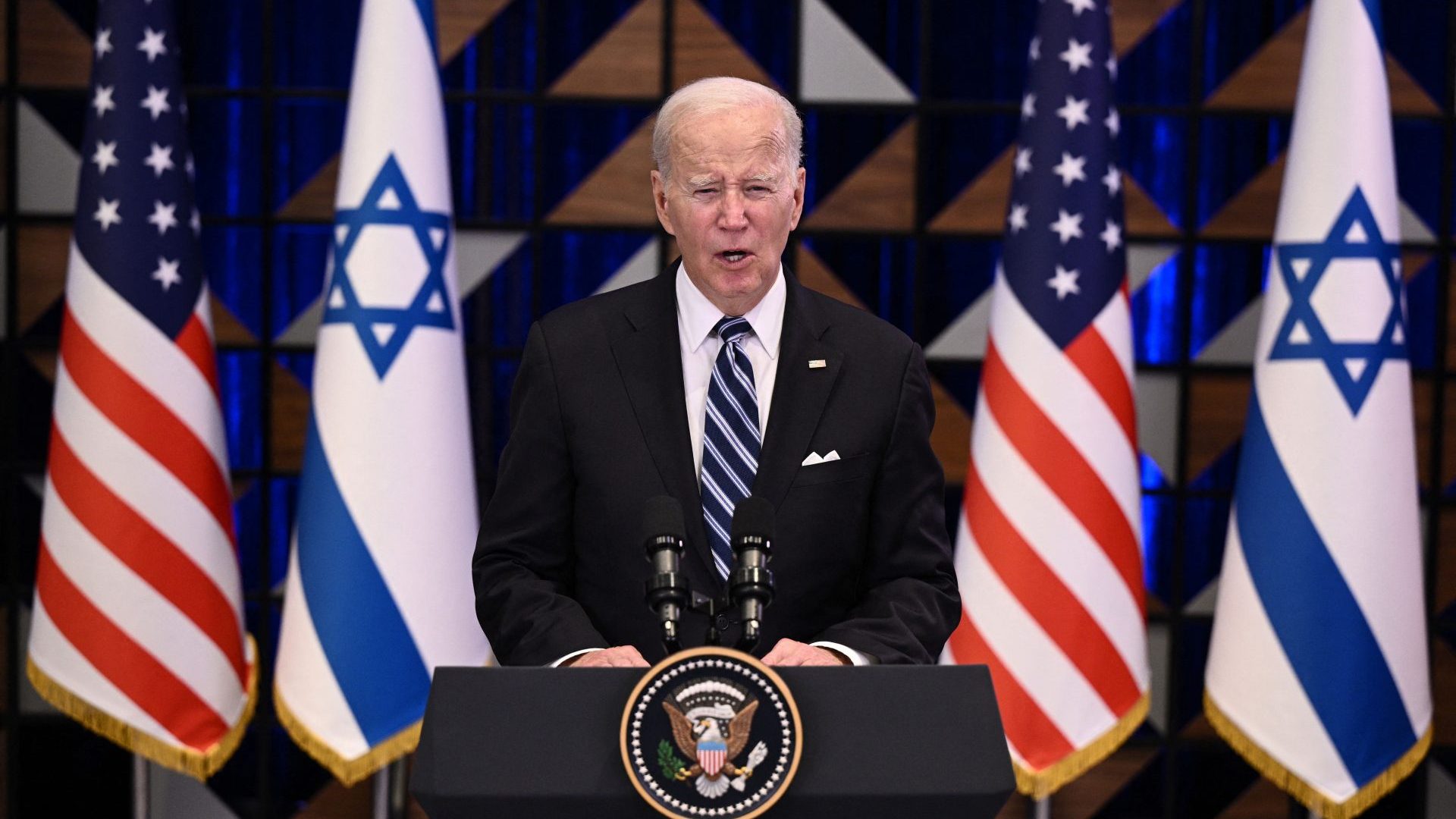

“We are the essential nation”: thus did Joe Biden, in his televised prime-time address from the Oval Office on Thursday, describe the United States. Indeed, he went further, recalling the formulation of “my friend”, the late Madeleine Albright, the first woman to serve as Secretary of State, who called America, “the indispensable nation”.

The governing thesis of the President’s statement was straightforward: “American leadership is what holds the world together. American alliances are what keep us, America, safe. American values are what make us a partner that other nations want to work with”.

Which was why, he explained, he was sending “an urgent budget request” to Congress – reportedly seeking $14 billion for Israel and $60 billion for Ukraine. Unable even to elect a Speaker, the House will struggle to deliver these funds as swiftly as they are needed, if at all.

Yet it was central to Biden’s purpose to juxtapose the desperate need for assistance in these two theatres of war with the current pettiness and introspection of US politics: “I know we have our divisions at home. We have to get past them. We can’t let petty, partisan, angry politics get in the way of our responsibilities as a great nation”.

This was a very different Biden to the tetchy, defensive figure of August 2021 who faced so much justified opprobrium over the hasty US withdrawal from Afghanistan and the return of the Taliban to control of that benighted nation.

Floundering in the heat of media cross-examination, he declared then that his hands were tied by the deal that Donald Trump had struck in February 2020; that he was “the fourth President to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan” and that he “would not, and will not, pass this war onto a fifth”.

Meanwhile, Afghan women faced the return of theocratic fascism after a generation of progress; and thousands, fearing for their lives, scrambled to get out before the mullahs returned – a desperation captured horrifically in the scenes of people clinging to a C-17 plane as it took off from Kabul airport, some falling to their deaths.

That terrible retreat marked the low point in Biden’s presidency and a moment of terrible self-reflection for the US and for the West. On the one hand, he had taken office promising that “America is back” and that the ugly isolationism of the Trump years was over. On the other, the abrupt departure from Afghanistan suggested that his foreign policy doctrine – if he had one – was no better than “America First” without the vulgarity of a red MAGA hat.

Yet Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 seemed to awaken something within Biden, to scratch at his conscience. This, after all, was a politician who had served for 12 years as the most senior Democrat on the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee and eight as Barack Obama’s vice-president. As Franklin Foer puts it in his recent book, The Last Politician: “When it came to foreign policy, Joe Biden believed he was the business… he had acquired a swaggering sense of his own wisdom about the world beyond America’s borders”.

That wisdom has always been, and remains, intuitive in character: quite unlike Obama’s coolly cerebral approach to foreign affairs and Trump’s brutally transactional and capricious style on the global stage. Putin’s assault on Ukraine did not alter Biden’s determination to keep American troops out of direct military confrontations (a point he spelt out once again in his Oval Office address). But it did persuade him of something else.

It had quickly become a refrain of his presidency that the world and individual nations alike were engaged in a mighty struggle between democracy and authoritarianism. But, to amount to more than a comforting T-shirt slogan, this conviction would have to be backed up with hard power. As he acknowledged in his address, the best way – the only way, in the final analysis – to “keep American troops out of harm’s way” was to keep the forces of autocracy and terrorism at bay.

To date, the US has sent Ukraine more than $46 billion in military assistance, way ahead of Germany and the UK. Were Trump to win a second presidential term in November 2024 and pull the plug, it is hard to see how Volodymyr Zelenskyy could hold the Russians back for long. The stakes are that high.

In his address, Biden audaciously but correctly linked the plight of Ukraine with the trauma suffered by Israel in the Hamas atrocities of October 7. This has already infuriated some in the media who long to frame the crisis in the Middle East as a battle between wicked Israelis and oppressed Palestinians. How dare he compare Gaza, which is smaller than the Isle of Wight, to Russia, a mighty federation covering 11 time-zones with a colossal nuclear stockpile?

But the US president adroitly identified the connection between the two theatres of war: “the assault on Israel echoes nearly 20 months of war, tragedy and brutality inflicted on the people of Ukraine, people that were very badly hurt since Putin launched his all-out invasion… Hamas and Putin represent different threats, but they share this in common. They both want to completely annihilate a neighbouring democracy – completely annihilate it”. Exactly.

Delivered in Biden’s by-now-familiar mumbling tones, the speech was still grand in its sweep and full of historical resonance. Sleep-deprived after his seven-hour trip to Israel, he noted that “I’m the first American president to travel there during a war”.

He recalled his journey by train in February to Ukraine: “I’m told I was the first American to enter a war zone not controlled by the United States military since President Lincoln” – an apparent reference to Lincoln’s visit to Fort Stevens in 1864 when he came under direct Confederate fire. He channelled the spirit of FDR, declaring that “just as in World War II, today patriotic American workers are building the arsenal of democracy and serving the cause of freedom”.

Truth to tell, though, it was not even his best speech of the week. In Tel Aviv, after meeting Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his war cabinet, Biden made a statement that bears comparison with John F Kennedy’s “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech in West Berlin in July 1963 or Ronald Reagan’s demand to Mikhail Gorbachev in the same city in April 1987: “Tear down this wall!”

It hardly needs to be said that Biden lacks Kennedy’s eloquence or Reagan’s Hollywood charisma. But his remarks on Wednesday were historic all the same. Whatever he does or does not achieve now, he has earned his place in the pantheon of consequential presidents.

Before Biden’s arrival in Israel, the groundwork had been laid meticulously. As a clear warning to Iran and Hezbollah, its terrorist proxy in the West Bank, two US aircraft carrier groups had been deployed to the eastern Mediterranean. On Sunday, the President gave an interview to the CBS show, 60 Minutes, and agreed that Hamas had to be “eliminated entirely”: the most important element of Israel’s self-defence strategy.

In his appearance with Netanyahu, he said that the appalling attack on Tuesday night on the al-Ahli hospital in Gaza, in which hundreds were killed, “was done by the other team, not you”. This marked a dramatic contrast to the reflexive verdict of the BBC and of many other news platforms that – as if axiomatically – the explosion must be the work of the Israelis (rather than a missile strike by Hamas or Palestinian Islamic Jihad falling short of its target).

In his statement, Biden did what he does best, which is to speak with empathy; a painfully acquired capacity that reflects the tragedies of his own life, especially the deaths of his first wife Neilia and 13-month-old daughter Naomi in a car crash in 1972, and of his elder son Beau from cancer in 2015.

“To those who are grieving a child, a parent, a spouse, a sibling, a friend,” he said. “I know you feel like there’s that black hole in the middle of your chest. You feel like you’re being sucked into it.”

Having said all this, in Tel Aviv, Biden had communicated to the Israelis what they badly needed to hear. With good historic reason, the Jewish people always fear, when they face persecution, that they must do so alone. Biden could not have been clearer in his benign insistence that this was not the case.

Welcome in itself, this authentic message of reassurance also enabled him to be candid about what comes next. “I caution this: while you feel that rage, don’t be consumed by it,” he said. “After 9/11, we were enraged in the United States. While we sought justice, and got justice, we also made mistakes”.

And there was more: “You are a Jewish state, but you’re also a democracy. And like the United States, you don’t live by the rules of terrorists. You live by the rule of law”.

Those who have alleged angrily that Biden went to Israel to hand Netanyahu a blank cheque were simply not listening. The president’s whole point was that the Israeli response to the pogrom of October 7 must be worthy of a democratic nation that recognises higher standards than the Hamas terrorists who killed 1,400 civilians on that day of infamy.

Will it make any difference? Already, the president’s intervention has compelled an agreement that the Rafah crossing between Egypt and Gaza should be opened and convoys of humanitarian aid begin to roll into the enclave.

Of course, the crossing needs to stay open throughout the crisis. This is only the very beginning of what is needed. But would Biden’s critics seriously be happier if he had not started the process?

The prospect of Trump winning next year poses an existential threat to the US and to the whole world. So, yes: as the presidential contest approaches, I have expressed, without apology, grave reservations about Biden’s cognitive and psychological condition. There have simply been too many episodes of public confusion and visible mental impairment to brush aside. Those concerns stand.

But I’d be delighted to eat any number of hats if he now steps up to the plate and, as he did so magnificently this week, continues to act with a consummate statesmanship that is all too rare on today’s international stage.

Israel’s land incursion into Gaza could begin at any moment; it may already have started as you read this. Terrible times still lie ahead: that, tragically, is a given, and has been since October 7. But it matters greatly that the Israelis know now that the world is at hand both to help and, in the spirit of friendship, to steer them away from vengeance and back towards the path of justice.

As Biden spoke on Thursday night, I was reminded of these lines from Tennyson’s Ulysses:

… and tho’

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.

It is October, 2023, and we are, unexpectedly, living in Biden’s World. There are many worse places to be.

For more on this week’s events in the Middle East, listen to the latest episode of “The Two Matts” podcast, in which TNE editor-in-chief Matt Kelly and Matthew d’Ancona talk to Tanit Koch about the response of the EU and Germany to the crisis.