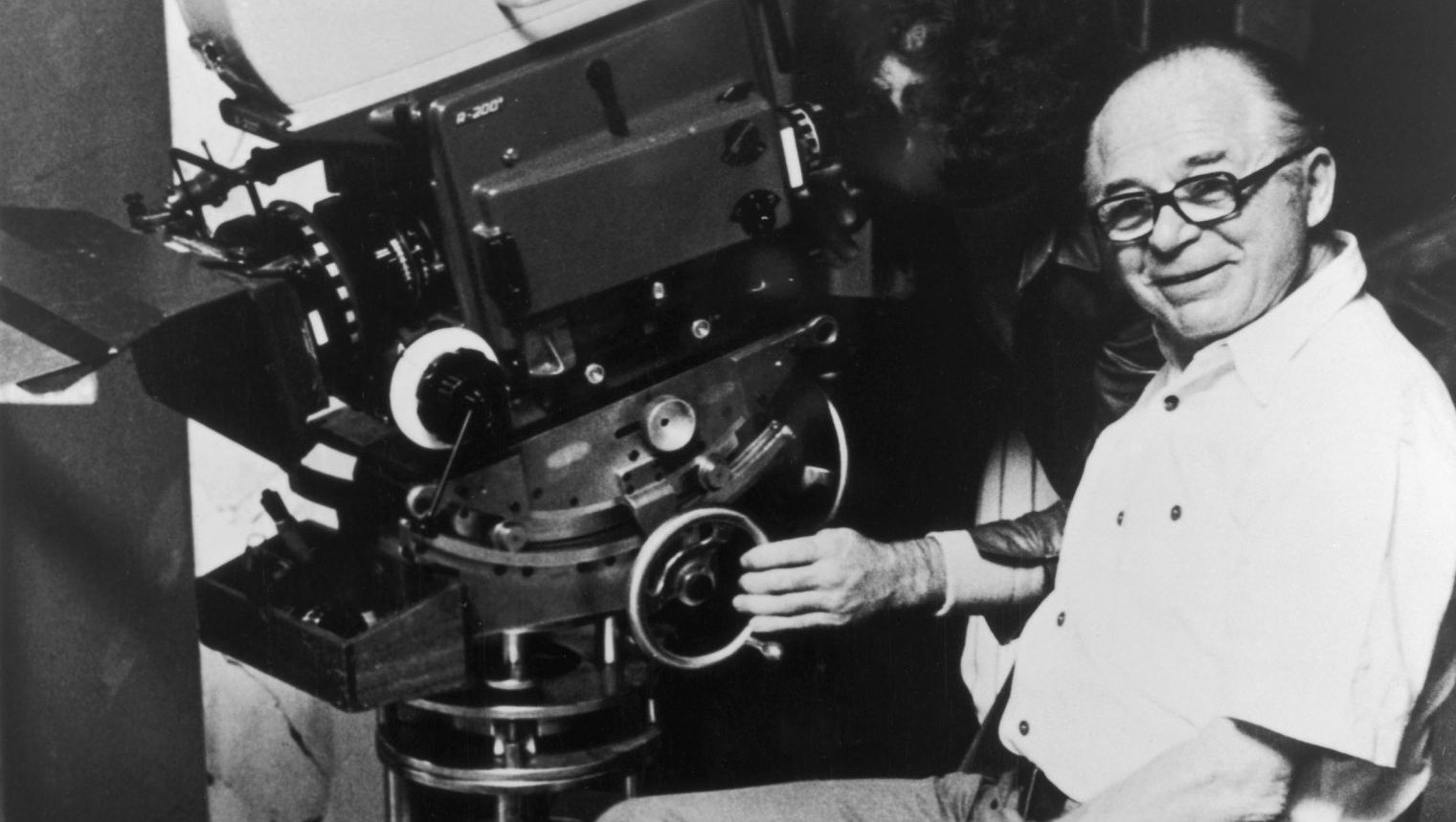

Billy Wilder moved to Vienna from his home town in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and became a journalist.

He often wore his hat like a journalist – cocked to the side: an imaginary pen in the brim, waiting for that scoop, that tip.

He skipped university and met the great American jazz leader, Paul Whiteman, when the band leader came to Vienna. Whiteman liked him so much that he took him along to Berlin.

This was the Berlin of the 1920s, the Berlin of the postwar Weimar Republic. Whiteman helped Billy to make connections in the entertainment field before Wilder became a writer, successful and able to survey the scene.

Before that, Wilder had been a taxi dancer, a young guy who danced with older women for money and drinks. He saw it all that way.

He was eventually offered a job at a Berlin tabloid and, through it, began to see not only the seedy, decadent, glorious nightlife but also the art scene, its refusal to accept the conventional, in a city that had nothing to lose. A city that told it like it was.

Theatre and art and film and literature exploded then, creating a cosmos of not only new ways of thinking, but of deep irony.

Beneath Weimar, beneath that endangered republic, was always the sense that life was fleeting; that it would all come to an end, and that so much was illusion. Even lies. So enjoy yourself; take none of it seriously; remember that human beings are fundamentally crazy.

And there is no God up in heaven.

Weimar lasted until 1933, when the Nazis came to power.

Wilder left and went to Paris, itself a place of turmoil and impending doom. Yet that insouciance, that knowledge that “some like it hot” stayed with Wilder, thrived in him, and when he could he found a way to go back to the spirit of Weimar; back to its shape-shifting and criminality, its irony.

There are three films that exemplify, for me, that Weimar spirit.

In 1948, he released A Foreign Affair starring his old pal from the Weimar days, Marlene Dietrich.

Jean Arthur, the epitome of what used to be called in the States “high, clean and holy”, portrays a member of a Congressional committee who come to post-war Berlin to, among other things, investigate Dietrich’s character, a woman suspected of having been a Nazi collaborator. Wilder stresses that Arthur’s character is from Iowa, and you get right away that she will be taken advantage of by Dietrich. And she is.

Dietrich is Weimar itself, its irony, and you can see that both she and Wilder are laughing at the US audiences who will see this film, may even be appalled at the casualness of the relationships, and the fun being made of a “good” American woman.

But Wilder’s touch is light. Ephemeral. Jean Arthur wins in the end and Dietrich returns to her life.

But it is with Marilyn Monroe that Wilder frames a kind of symbol of Weimar and its tragedy.

In The Seven Year Itch, Marilyn portrays the quintessential dumb blonde, the girl who can’t help it. She is the summer vacation for a guy whose family has gone ahead of him to their holiday spot. While they’re gone, he discovers that he is experiencing that “itch”, the need to play away, and conveniently Monroe appears.

Her very presence shows not only his hypocrisy but the hypocrisy of the American dream with its roots in a “solid” marriage. She upends by her very presence. And in that famous scene, where her dress upends – and of which Wilder did a lot of takes surrounded by an audience from the street – he reveals not just her underwear, but the sham of the “sex symbol” construction itself. She is vulnerable. In the wind.

His next and last film with MM, Some Like It Hot, ends with the line: “Nobody’s perfect”. Just as no one was in Weimar.