Half a century ago we were witnessing the conclusion of what came to be known as the Match of the Century – the 1972 chessboard clash between defending world champion Boris Spassky of the USSR and the most devastating challenger of all time, the American Grandmaster, Bobby Fischer. “Each match has something mystic about it,” Spassky has said, and on this occasion there can be no argument.

Fischer had destroyed a procession of greats on his way to the final – Taimanov, Larsen, Petrosian – as if they were mere chaff in the wind. The final, held in Reykjavík between the Soviet and the American, seemed to transcend the game itself, becoming a metaphor for the clash between East and West, communism and capitalism.

The figure of Fischer is well known – the eccentric American stormed to overwhelming victory in the final, only to shatter the dreams of his millions of fans around the world by retiring into voluntary seclusion for 20 years.

Spassky is perhaps the less familiar figure. During my chess career I played against him, twice – the overwhelming impression I gained was of a youthful, dynamic tactician, capable of destroying the greatest with sudden bursts of aggression.

Spassky was certainly all of those things. He had also been a child chess prodigy of prodigious power, as had other greats, such as Paul Morphy, José Capablanca, Sammy Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer himself. Spassky learned to play chess when he was five, on a train fleeing the Nazi siege of Leningrad. By the age of 10 he’d beaten the Soviet champion, Mikhail Botvinnik, in a simultaneous display, where the champion played several opponents at the same time.

It was a remarkable achievement, but in the world of chess, other prodigies had achieved even greater feats. Sammy Reshevsky, for example, defeated his first Grandmaster, David Janowski, in a one-on-one tournament game, also aged 10. After that game the diminutive Reshevsky jumped up and down in the taxi on the way home in New York, ran up the stairs to his parents and sang with joy. Spassky was regarded as extraordinarily talented, though he was not quite a prodigy in the Reshevsky league. But Spassky’s later career would take him to greater heights than Reshevsky ever achieved.

I first had the pleasure of watching Spassky in action at the Hastings tournament of 1965-66, where he won first prize (shared with the German Grandmaster Uhlmann). Then, in 1968 I faced him for the first time across the board in the Lugano chess Olympiad.

Spassky had a formidable presence. Across the board it was very difficult to know what he was thinking. He was immaculately dressed and had a sense of western style which his Soviet colleagues lacked. Most Grandmasters were chain smokers of cigarettes, and one Dutch Grandmaster, in my presence, once set fire to an ashtray piled with his stubs. Spassky was different – he smoked a pipe. As all my other English teammates succumbed to the Soviet steamroller, I salvaged the sole draw for our side, much to my own astonishment.

Spassky went on to become world champion in 1969, obliterating famous opponents in his path, in victories studded with brilliant sacrificial thunderbolts. His victims included David Bronstein, the inspiration for Kronsteen, the James Bond chess mastermind in From Russia with Love. Even Bobby Fischer himself had succumbed three times to Spassky before their match in 1972. All this was accomplished with the eyes of the Soviet state firmly upon him – most of the Soviet chess players hated the regime, but kept their mouths shut and remained apolitical. “In the Soviet system a person was state property – a cog, which they could turn as they wished,” Spassky has said. “At the time chess served politics. Politics reduced it.”

But as his greatest test approached, things started to slip. At a competition in Moscow in 1971, he suffered a surprising loss of energy, finishing in a share of sixth place, behind the former champion Tigran Petrosian, who outclassed Spassky in their game. This was not a good omen for the match against Fischer, a ruthless calculator, near-perfect technician, fireball of intimidating energy and a master of off-board psychological warfare.

In the lead-up to the Reykjavík final of 1972, much of the media furore surrounded the cultural clash between capitalism and communism. Yet, paradoxically, Fischer made a poor symbol of capitalism. He had no real material instincts and turned down most of the commercial endorsement offers that came his way. In an ironic parallel, Spassky was scarcely a hardline son of Lenin. His Marxist-Leninist credentials were severely defective. Spassky was a Russian nationalist, but also a monarchist, and also very religious – a very unusual amalgam for the time.

But the match itself was regarded by most experts as one of the most exciting and sternly fought of its kind. The lone voice who criticised the 1972 final for what he saw as a low standard of play was that former prodigy, the now veteran and embittered Sammy Reshevsky. Having failed narrowly in his own ambitions to become world champion and having been thwarted on numerous occasions by the younger Fischer, Reshevsky had several axes to grind. There were certainly blunders made by both players at Reykjavík in 1972, but no more than usual in any battle at the top of world chess.

Other critics, such as Argentina’s Miguel Najdorf and England’s Harry Golombek, referred to the tigerish quality of Fischer’s play, and were less dismayed by his few errors. Some expert onlookers even saw genius in Fischer’s play. His best moves were, one remarked, the chess equivalent of a symphony by Mozart.

With the world’s attention on him, Spassky famously lost to Fischer, having spurned the chance to win by default when the American failed to show for the second game, putting him 2-0 down. Spassky was urged to end the contest or at the very least return to Moscow for a break, but refused. “I resisted, I wanted to play. What a fool I was,” he has said.

Finally victorious, the American promptly vanished and Spassky, the now wealthy loser, returned to Moscow. No serious official action was taken against him for refusing to walk out on Fischer, but Spassky has told an interviewer: “The sports committee couldn’t forgive me for declining the chance to retain the world championship title. I could easily have done that simply by leaving the match. I had every justification.”

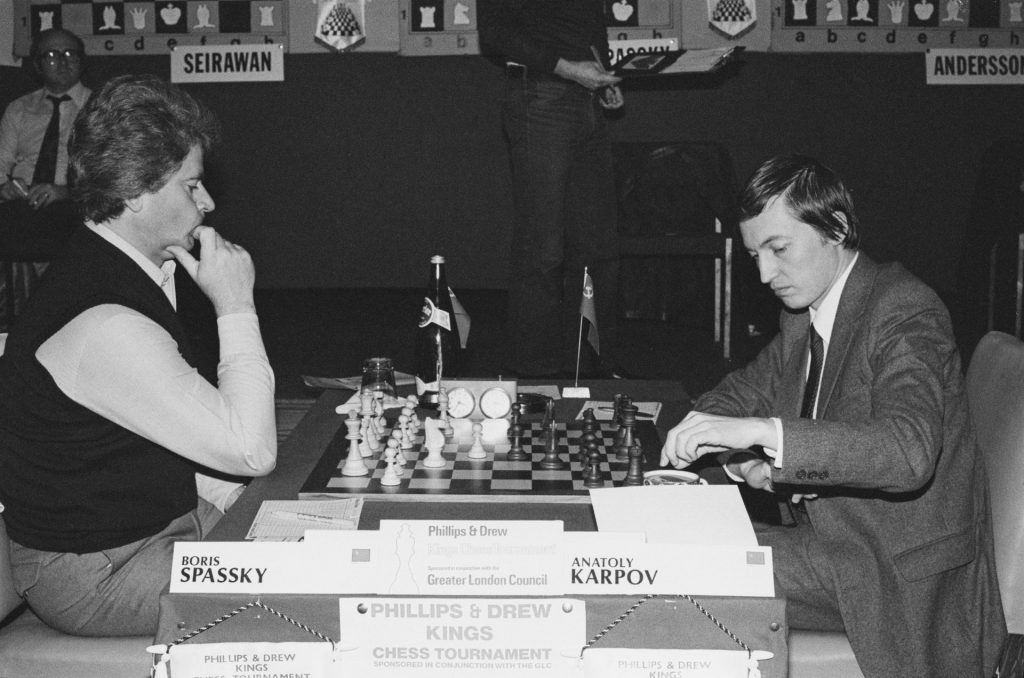

Spassky’s loss was a blow to the prestige of the Soviet chess system. Reforms were introduced to make the game more competitive and to identify a player who could challenge Fischer. That someone turned out to be the prodigious Anatoly Karpov.

Meanwhile, though, Spassky continued to shine, deploying an arsenal of chess opening discoveries, which he failed to use against the wily Fischer. In the first round of the German International Championship at Dortmund 1973, I faced him for a second time.

To my horror I faced Spassky with Black, meaning he played first, which is rather like having the serve against you for an entire game of tennis. Inscrutable as ever, Spassky betrayed no signs of being demoralised by his recent loss to Fischer – and besides, he crushed me so quickly. Spassky won the tournament with the loss of only one game. That loss was the sole hint of any deterioration in either his morale or strength.

He went on to win the 1973 Soviet Championship but then, the following year, disaster struck. Spassky reached the semi-final of the world qualifying tournament where his opponent was the relatively inexperienced Anatoly Karpov, 15 years his junior. By now, mid-1974, it was evident Fischer had no intention of defending his title, and Spassky had all to play for. The outcome was a catastrophe for experience against youth, as Spassky crashed to defeat. Karpov went on to become world champion.

Soon after, Spassky was permitted to emigrate to France. He married a French woman, who became his constant companion and supporter. But this was not retirement. In the world title cycle of 1978, Spassky was one victory away from the revenge challenge against Karpov. But before that, he had to get past the defector Viktor Korchnoi in Belgrade.

For this match I acted as Korchnoi’s chief second, meaning I was his appointed adviser, permitted to discuss the game and talk tactics. Korchnoi was an interesting character. His main weakness was a near lethal cocktail of acute paranoia and morbid superstition. Perhaps alert to this, Spassky wore a visor during play and spent long periods hiding in a room backstage, only emerging to actually execute his moves. Spassky’s representative, the ideologically rigid Soviet Grandmaster Igor Bondarevsky, made a series of weak excuses for what was going on, but it was clear that these prolonged absences were an act of gamesmanship, intended to wind up Korchnoi. Seeing this absurd performance, it felt to me that there had been a kind of deterioration on Spassky’s side. Did such a great player need to resort to such low tricks? I remember seeing his hand-written records of the games. Spassky’s formerly bold, flowing handwriting had changed. It had become smaller and more crabbed.

Unfortunately, Spassky’s ruse worked and Korchnoi drew what was for him the inevitable conclusion: that harmful atomic rays were being beamed at the stage by a portable nuclear reactor which Spassky had somehow acquired and clandestinely smuggled into the theatre. Korchnoi’s fears were stoked by his friend and companion Petra Leeuwerik, an equally paranoid former terrorist who had spent 10 years in the Soviet concentration camp of Vorkuta for trying to blow up a train.

As the paranoia took hold, Korchnoi’s lead in Belgrade began to crumble. But wiser heads in his camp explained the impossibility of introducing a nuclear reactor into the playing hall, and after this reassurance Korchnoi recovered his poise and Spassky was eliminated.

Spassky’s prospects of regaining his title were now vanishingly small and his results began to show it. Ambition had waned to zero and short draws began to proliferate in his games. As a competitor in almost any event, Spassky remained a great name, a colourful adornment to any line-up of Grandmasters. In truth, though, the creativity had expired.

In the London Grandmaster tournament of 1986, which I organised, Spassky drew every game, except that against the British Grandmaster James Plaskett. Plaskett turned down Spassky’s draw offer and was duly punished by furnishing Spassky’s sole win.

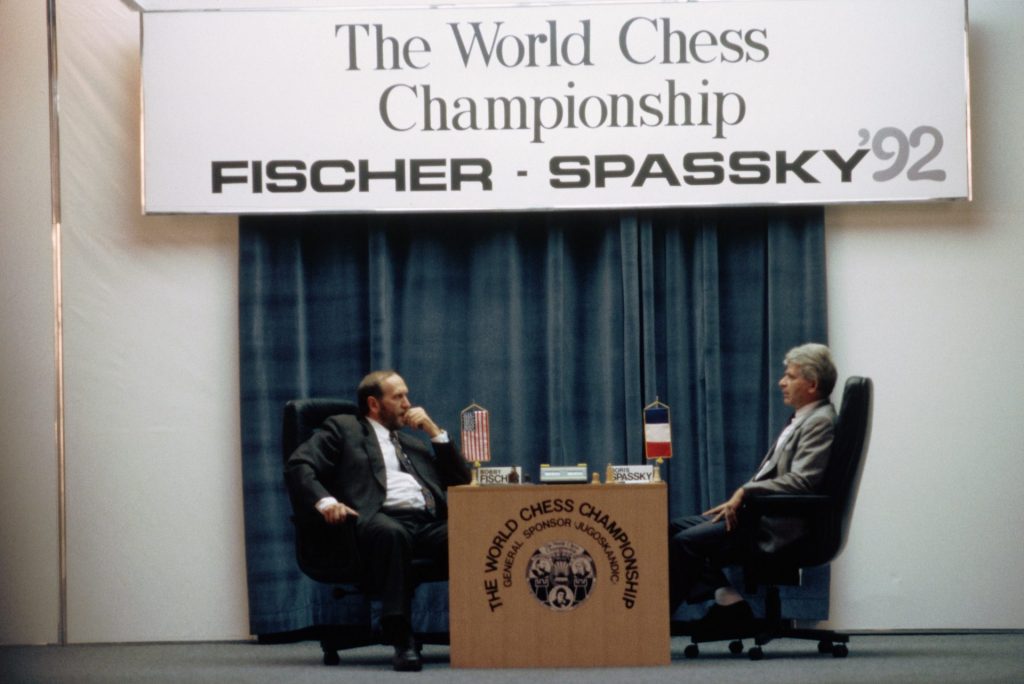

And then, 20 years after their epic contest in 1972, Fischer succeeded in raising $5m from a Serbian backer to stage another contest against Spassky. In Fischer’s mind, it would be a world championship, taking off from the point where Reykjavík 1972 had left off.

When the rematch happened in 1992, it was clear both were past their sell-by date. Barring the occasional flash of genius, the games were marred by elementary blunders and feeble openings. Although Spassky emerged as the loser yet again, both his fortune and future were now secured. He was able to escape the treadmill of tournaments and could confine himself to exhibition matches where high fees but little effort was involved.

Spassky has not played a serious game of chess since 2009. In 2012, under somewhat mysterious circumstances, he abandoned France and returned to Russia and at the age of 85 he is the oldest surviving world champion. He has returned to the Russian Orthodox Church and still regards himself as a Russian nationalist, though his views on Putin’s invasion of Ukraine are unknown. He describes himself as being “in the endgame of life,” and recently told an interviewer: “Do you know that joke about two chess players? Apostles Peter and Paul tell them: ‘Chess is a sin, so you don’t get into heaven. But you can choose between socialist and capitalist hell.’ ‘Of course we choose socialist hell!’ ‘Why?’ ‘There’s always a shortage of either firewood or cauldrons!’”

Spassky will go down in chess history for many reasons. But one memory is especially striking. In the 1972 Reykjavík contest, he lost Game 6 to Fischer in what was a brilliant victory for the American. It is a measure of his greatness that, despite the loss, and in full view of the world, Boris Spassky applauded.

Raymond Keene is a chess grandmaster, author and columnist who was the Times’ chess correspondent for more than 30 years

Boris Spassky

1942 Five-year-old Boris Vasilievich Spassky is taught chess moves on a train journey while being evacuated from Leningrad during the second world war siege.

1947 Now recognised as a prodigy and being coached by Vladimir Zak, who will later coach Viktor Korchnoi, the 10-year-old Spassky defeats 36-year-old future three-time world champion Mikhail Botvinnik in a simultaneous exhibition match.

1953 Finishes fourth in his international debut in a tournament held in Bucharest, Romania; it is won by his new trainer, Alexander Tolush.

1955 Wins the world junior championships in Belgium. Named a Grandmaster at the age of 18, at the time the youngest ever.

1956 In January, Spassky finishes joint-first in the Soviet championships, but loses in a play-off. It is the start of a four-year slump in his career, although in 1960 he does beat Bobby Fischer in their first meeting.

1961 Splits with Tolush and also with his first wife, Nadezda Konstantinovna, after two years of marriage. He describes their relationship as being like a meeting between “two bishops of different colours”. Develops all-round style of play under new coach Igor Bondarevsky. Wins the first of two Soviet championships.

1966-69 Spassky plays Soviet compatriot Tigran Petrosian twice for the world championship, losing their first encounter by 12½ points to 11½ but exacting his revenge three years later to take the title for the first time by 12½ points to 10½.

1972 In the “Match of the Century”, Spassky is defeated 12½-8½ by Fischer in the world championship held at the Laugardalshöll arena in Reykjavík despite the American losing the first game and forfeiting the second.

1973-80 Spassky initially puts the disappointment of Reykjavík behind him to win the 1973 Soviet championship against a strong field. But, even with Fischer refusing to take part, his quest to regain his world title falls short when he loses in qualifying tournaments to eventual 1975 champion Anatoly Karpov and then to 1978 runner-up Viktor Korchnoi.

1976 Leaves the USSR for France with third wife Marina Yurievna Shcherbachova (he was married to Zakharovna Solovyova between 1967 and 1974). He later becomes a French citizen and represents the country in tournaments, though by the late 1980s he has become only a mid-tier player.

1992 Accepts the equivalent of £2.7m in today’s money for a rematch with Fischer, who has not played a tournament for two decades. Spassky is easily defeated.

2012 Spassky, who has suffered strokes in 2006 and 2010, is declared missing from his apartment in Paris. He eventually emerges in Moscow, to where he says friends have helped him escape. “I am not a rich man, but maybe someone had a financial interest in seeing me dead as soon as possible,” he says.