Brexit-imposed barriers to the import and export of goods at the UK’s borders with the EU have caught the attention of the media – and nowadays, even of politicians. Yet the UK is not really a manufacturing economy these days so much as a services provider. Services make up 80% of the British economy, and unusually, services make up almost half of our exports as well. Services runs at a trade surplus, compared with the massive trade deficit we have in goods, importing far more than we export.

When we say “services”, we think of financial services and especially the City of London. Brexit has “chipped away” at its importance, says the Financial Times, with no jaw-dropping desertion of the Square Mile but thousands of jobs gone to Europe and the crown of Europe’s biggest stock market lost to Paris.

Yet the UK is a huge exporter of many other services as well. There’s advertising, accountancy, acting, auditing, and architecture – and they are just some of the ones beginning with an A. Services also cover countless other areas of business; from design, telecoms, maintenance, technology, music, marketing and the law to education, conference organisers and zoological advisers. The sector embraces consultants, experts and advisers in every economic sector, business and industry imaginable.

Yet something unpleasant is happening to our services-based economy. It began when the Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA) that Boris Johnson and David Frost signed with the EU had very little to say about services beyond the City. Then the new free trade deals agreed by Liz Truss – remember her? – were also light on detail about services.

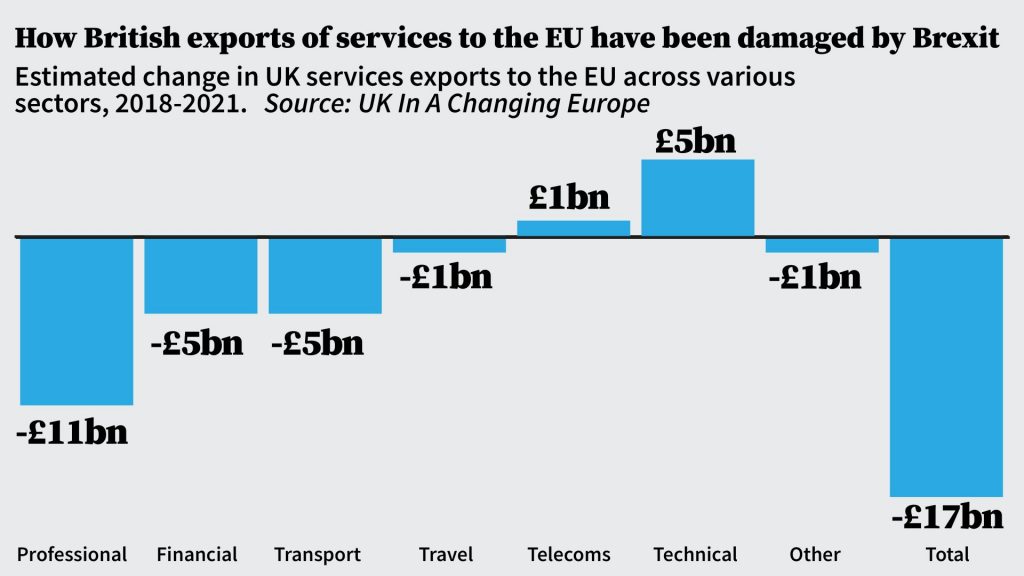

Meanwhile, according to the think tank UK in a Changing Europe: “Between 2018 and 2021, exports of goods and services both fell by 12%. Goods imports fell by 7% but service imports dropped by 20%.” Not only that, but “goods imports had fallen by 15% in 2020 and partially recovered in 2021, whereas service imports fell and remained depressed.”

“The reasons are many and varied, but the basic problem is that the British government failed to negotiate a deal on services with its largest market, the EU.”

For a start, as Sarah Hall, professor of economic geography at Nottingham University, explains, there is the small matter of visas. Membership of the single market meant you never needed one, but now “if a lawyer or an architect wants to travel to the EU to provide a service they will need a visa”.

This sounds simple enough, except each member state of the EU is responsible for handing out its own visas. These are, of course, good only for one country, each comes with its own rules and regulations, and all have to be applied for in advance. Not only that, but while big companies can afford the time and expense of visas, smaller companies cannot, and so they simply stop trading in the EU.

If they do try to carry on, as Prof Hall points out, they face further hurdles, because to classify yourself as an independent professional for travel purposes “you need to have a degree and six years’ relevant experience”. Rather difficult for many service providers; not everyone would pass those criteria. All of a sudden, having an Irish passport is looking like a must-have on your CV.

Then, as Hall told me, there is the mutual recognition of professional qualifications or, to be more accurate, the loss of mutual recognition. The UK asked for this in the Brexit negotiations, but the EU said no. As a result, EU firms would have to prepare a due diligence report before, for instance, employing a UK lawyer. As many EU members have different rules on what qualifications they accept and therefore who they accept, the whole thing is a minefield.

The TCA did set up a joint committee to negotiate further on mutual recognition of qualifications. Strangely enough, as with the Horizon programme, the vital subject of data adequacy and financial services, the UK has made virtually no progress. A logjam that it desperately needs to get through, but where progress will be glacial unless the Northern Ireland Protocol row is resolved.

The new rules on how long visitors can stay in the EU are also hitting services businesses. Currently UK citizens cannot visit for more than three months in every six months, but that covers holidays as well. HR departments in the UK are going to have to keep a sharp eye on where you are taking your summer and winter holidays if they don’t want to see you sent home early from an important business trip.

There are huge grey areas here. Speaking at a conference is work, but is just attending a sales conference work if you don’t sign any deals there, but do when you are back in the office? No one is quite sure, and if they wanted to be difficult, EU member states could easily make life far harder for British service providers.

All these changes have hit every industry, but one that has gained a lot of publicity and illustrates how messy trading with the EU has become is the music business, where touring in the EU has gone from driving your van to France for a gig to a red-tape nightmare.

Every band now needs a carnet, which is a list of every instrument and piece of equipment they carry into each country. It has to be checked on the way out and on return to make sure none of it has been sold. Some European customs officials are now asking for Goods Movement Reference numbers too – the GMR links together several customs declarations all at once and is another post-Brexit expense.

There’s an argument about whether they are even needed, but when Dave Webster of the Musicians’ Union asked the government for guidance, he could get no clear answer, “so the advice is get one to be on the safe side”. This is the quality of advice the government is providing to British business after Brexit.

Transport is another issue for more successful bands and orchestras alike. Their specialised trucks are hand-built to protect vital and very expensive instruments and equipment on tour. But EU rules limit the number of stops that UK-registered lorries can make in the EU to three. Any concert tour longer than that has to hire EU vehicles or return to the UK after every third concert. Expensive and a waste of time and effort.

Bands are having to spend time and money planning and dealing with the red tape in advance, something Webster says is hurting business.

“It is having an effect on the industry already, people are looking at the costs around Europe now and asking ‘is it financially viable?’ It’s damaging to UK culture, it’s a loss to the European fanbase of UK bands and while some bands are touring again post-Covid, they are finding it more problematic and in some cases they are making a loss doing so,” Webster says.

While big acts like Ed Sheeran and Dua Lipa have management teams to do this kind of work for them, the next Ed Sheerans and Dua Lipas have not. Therefore British artists will now find it harder to break through. Something Britain has been famous for since the 1960s has been broken by Brexit.

In the end, none of this should come as a surprise. Margaret Thatcher promoted and championed the single market, and she made sure it covered not only goods but also services, and that it worked to Britain’s advantage.

This was for decades a huge win for the UK economy, enabling it to sell services across the continent, because as Hall puts it, “a single market goes far, far, far, further than other trade deals on service-sector liberalisation and particularly on passporting. That is, where a company based in the UK could supply services to Germany from that UK base. That is really significant, and the UK played an important role in shaping that and obviously benefited significantly from that.”

The single market was a godsend for Britain’s service sector. It need not have been thrown away, even in the Brexit negotiations. Johnson and Frost thought better, and with it they turned a British success story into a grim tale.