Two deaths overshadowed an ominous 12 months for Britain and the planet. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports.

According to a Mayan prophecy, doomsday was set for December 2012. In the event, 2016 was the year that really had a sense of the apocalyptic about it, as political catastrophe made it feel like the sky was falling in. It was a year of loss – of our sense of direction and even of our sense of self – but also of defining musical geniuses that life had seemed unimaginable without.

The year had started hopefully with a series of unifying events, as president Obama made a historic visit to Cuba as relations thawed, sanctions were lifted on Iran, and Pope Francis and Patriarch Kirill signed an Ecumenical Declaration after 1,000 years of estrangement between the Catholic and Russian Orthodox churches.

Even Guns N’ Roses, mired in acrimony for two decades, were back together, as original members Axl Rose, Slash and Duff McKagan launched the knowingly-titled Not in This Lifetime… Tour. The Rio Olympics united the world in the most colourful games yet, and Pokémon Go captured the imagination of the whole globe.

But there was a far darker side to the year. There were major terrorist attacks in Brussels, Istanbul, Nice and Orlando, and the obscenity of 85-year-old priest Jacques Hamel being murdered at his own altar in Normandy. Domestically, war was the theme, as the Chilcot Inquiry report was released and the centenary of the Battle of the Somme was marked with a two-minute silence and artist Jeremy Deller staging We’re Here Because We’re Here, which saw 1,600 men in First World War uniforms appear at train stations and shopping centres across the country.

For all the controversy of the Panama Papers, junior doctors’ strikes, Tory and Labour leadership elections, and a UKIP leader who lasted only 18 days, it all seemed like routine stuff versus the Brexit referendum campaign, which veered between the absurd and the horrific, culminating in the murder of Jo Cox – an event that would cast a pall over the whole year and beyond.

By June 15, the referendum campaign was reaching fever pitch. In a surely unintentional echo of the Sex Pistols’ jubilee year publicity stunt, on that day Nigel Farage headed a flotilla of fishermen and UKIP funders, sailing up the Thames to parliament while playing The Great Escape theme.

They were met by Bob Geldolf’s ‘In’ campaign fleet, who proceeded to blast out Dobie Gray’s 1964 single The ‘In’ Crowd, before Geldolf’s vessel was doused with hoses and forcibly boarded by the fishermen. The farce was dubbed the Battle of the Thames. Having participated in the event by taking to a dinghy with her husband and small children, Cox was murdered the following day, and the national mood was turned on its head.

While what was happening to Britain was devastating, the implications of a Trump presidency were even more far-reaching. Music played a key role in the Trump/Clinton face-off. The Republican used the Stones’ You Can’t Always Get What You Want as his campaign theme tune, and the band joined Adele, Neil Young, Aerosmith, and REM in sending Trump cease and desist letters regarding his use of their music.

Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, used a trio of studies in feisty defiance by American female solo artists at her rallies: Rachel Platten’s Fight Song, Sara Bareilles’ Brave, and Katy Perry’s Roar. Clinton’s choices were appropriate in a year when women were ruling the charts.

Dua Lipa’s hit debut single, Hotter Than Hell, launched a new star, while Australian artist Sia became the first female artist over 40 to have a US No.1 since Madonna over a decade before when her Cheap Thrills topped the Billboard chart in August.

Work, the lead single from Rihanna’s eighth album, Anti, was also a US No.1. Female artists were also all over the album charts. Adele’s 25, released in November 2015, continued to do great business, while Beyoncé’s Lemonade was hailed as a creative rebirth, and she won a record eight awards at that year’s MTV Video Music Awards.

Lady Gaga’s October LP Joanne was more stripped-down than previous efforts and gave her a fourth consecutive US No.1 album. Meanwhile, Taylor Swift became the first female artist to win the Album of the Year Grammy twice, adding a win for 1989 to 2010’s Fearless.

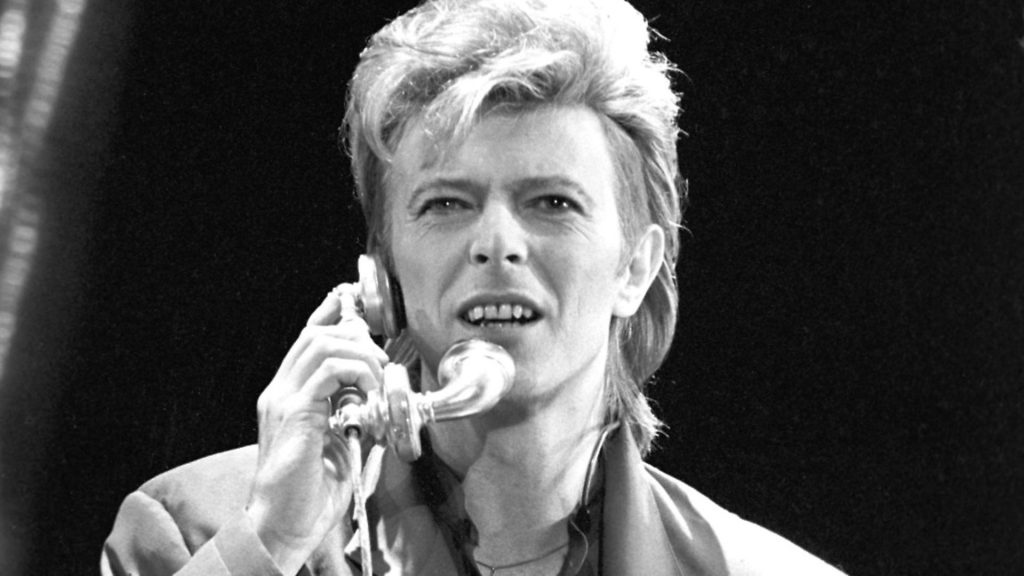

But the dominant musical events of the year were the deaths of two unassailable stars – Prince and David Bowie. Bowie had shunned the public eye ever since his 2003 heart attack, living a relatively anonymous life in New York. While he had lost himself sometime in the mid-1970s, Bowie had gone on to become that rare thing – a contented megastar – allowing him to ditch rock cliché and write about middle age with rare clarity on his later albums.

While relationship breakdown, the experience of aging, and suburban ennui had featured on Hours (1999), Heathen (2002), Reality (2003) and The Next Day (2013), on Blackstar, released on January 8, 2016 – his 69th birthday – illness and death became Bowie’s themes.

His 25th studio album, it went in a bold new direction as Bowie recruited a New York jazz band to make a record that was experimental, yet angular and forensic. Two days after that release, Bowie died, his cancer diagnosis having been kept entirely secret until that point. The record was immediately interpreted as a coded final farewell, even though Bowie did not get a terminal diagnosis until after recording was complete.

Even so, Bowie’s final LP was so very poignant after the fact. Blackstar’s title single contained the lyric “Something happened on the day he died/ Spirit rose a metre and stepped aside”, while Lazarus, opened “Look up here, I’m in heaven”, was seized on with relish by the press. The Lazarus video was in fact thoroughly knowing of how his illness would be sensationalised when word of it got out, featuring a bed-bound Bowie who ultimately backs into a wardrobe in a pantomimic but utterly poetic representation of death. Meanwhile, Sue (Or in a Season of Crime) spoke of clinics and x-rays and “your stone/ For your grave”.

Bowie had no funeral and no celebrity-studded tribute concert, and the closing track of Blackstar, I Can’t Give Everything Away, came off like his final claiming of his right to privacy. Opening “I know something is very wrong”, and speaking of “skull designs upon my shoes”, it acknowledged the spectre of death, but its protest “Seeing more and feeling less/ Saying no but meaning yes/ This is all I ever meant/ That’s the message that I sent” was perhaps a disavowal of the role of sanctified figure and oracle, while the song’s title could be read as a statement of resistance against the voracious appetite of press and public.

Three months later, on the morning of April 21, Prince was found dead in a lift at his Paisley Park estate in Minneapolis. He was 57.

As with the sudden death of an apparently healthy 50-year-old Michael Jackson seven years before, mystery initially surrounded his demise. But a familiar picture quickly emerged of a lost soul, holed up in his estate with a variety of hangers-on in what may be dubbed ‘Graceland syndrome’.

The star, it turned out, was yet another victim of America’s opioid crisis, the cause of death being confirmed as a fentanyl overdose. It emerged he had experienced another overdose just a week before, having been taken ill on his plane when flying back from Atlanta, where he had just given what turned out to be his last ever performance. At that concert, he had opened his second encore with a cover of Bowie’s Heroes in tribute to an artist who had made so much of what he later achieved possible.

How Prince – a Jehovah’s Witness who was apparently so clean-living that Paisley Park was strictly an alcohol and meat-free zone – had died in such a way caused confusion, but his use of pain medication was directly related to his music.

The artist was halfway through his Piano and A Microphone Tour, which was exactly that – Prince, otherwise unaccompanied – and was experiencing pain in his hands from the gruelling nature of each night’s performance.

After his initial overdose, he reportedly refused to swear off the pills, knowing that he could not continue to perform without them. The feel of that tour, at which recording was prohibited, was captured on a 1983 demo tape released posthumously as Piano and A Microphone. That tape captures a pure talent that controversy and the full, flamboyant trappings of rock iconicity often obscured, capturing the artist playing just for himself, flowing between songs in a breathtaking display of innate musicality.

We lost our sense of direction in 2016, as a new and bewildering period in history began, along with a battle over the values that would determine our future trajectory. Our musical heroes so often stand for creativity and freedom – none more so than those we lost in 2016 – and as long as the battle for such values goes on, it can still be won.