The events of the referendum night, writes JAMES BALL, shine a fascinating light on the world of finance, polling and politics

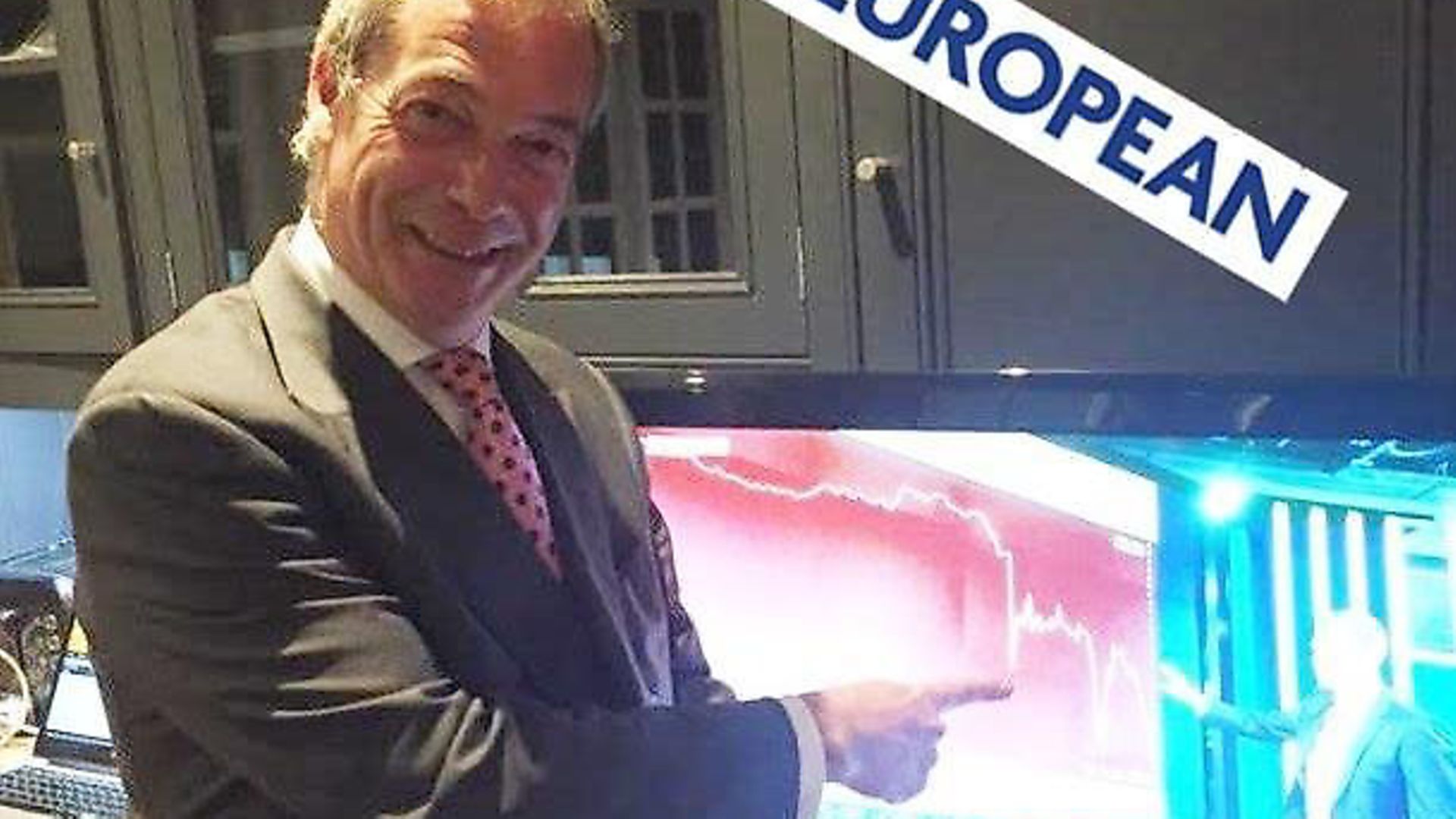

It was the week a major news organisation accused Nigel Farage of perhaps the most cynical manipulation of financial markets in history

Bloomberg, the international financial news agency, suggested the former UKIP leader might have deliberately misled broadcasters into believing Remain had won the referendum, on the evening of the June 2016 vote. This, Bloomberg alleges, might have been with the intention of keeping the value of the pound artificially high until the true result later sent it plummeting.

The accusation, roundly denied by Farage, is that this gave hedge fund investors, some of whom are associated with him, a window of opportunity to bet against the value of sterling – bets that would pay off spectacularly once the actual result was known.

These are extraordinary claims and, in Farage’s own words, are ‘wholly untrue and unfair’. Without having access to the evidence Bloomberg claims, it is impossible to say if there are grounds for a case to answer. Certainly, the MEP has been unequivocal in his denials, saying ‘of course’ he did not try to mislead people by conceding defeat in the vote. Speaking to us after allegations were published, he accused Bloomberg of engaging in a groundless conspiracy.

But the events of that night, just over two years ago, certainly shine a fascinating light on the world of finance, polling and politics, and how the three can sometimes entwine. Farage’s alleged role notwithstanding, at the heart of Bloomberg’s report is the suggestion that hedge funds aimed to ‘win big’ from trades on the night of the EU referendum by analysing private exit polls. It won’t have come as a great surprise to those in the industry: on any night likely to move markets as much as the Brexit result, you can be sure hedge funds will be all over it. That is literally their job.

Hedge funds make profit by trying to guess what’s about to happen and how the markets will respond to it, and because there are billions in profit (or loss) at stake, they will take any edge they can to help inform their decisions.

This is essentially what hedge funds are for: by giving lots of bright analysts reasons to try to find the state of countries, companies, and debt, they are supposed to help markets accurately reflect information – as well, of course, as making money for their investors.

The industry can be famously hard-edged: one of the main driving factors of 1992’s Black Wednesday – when Britain crashed out of Europe’s exchange rate mechanism – was George Soros’ hedge fund making a huge bet against the country in the expectation the government would be unable to hold its position against his fund’s trading position. In this instance, the fund was not so much predicting an event as helping to make it happen.

Compared with Black Wednesday – a hedge fund taking on a government in a way that forced it to drop one of its key foreign policy positions – hedge funds spending a few hundred thousand pounds (or even a million) to commission some private polling to try to get insight on the result of the Brexit referendum is small beer. We might feel uncomfortable that they have access to so much higher-quality information than we do, but that happens every day. It’s just that this time, we found out.

For the hedge funds, Brexit might have been a big night at the office, but it was essentially their business as usual. That’s not true of the politicians, though, and this is where the Bloomberg story raised intriguing questions.

As voting ended on the evening of June 23, 2016, Farage seemed to concede the result of the referendum, telling reporters he had information from ‘friends in the city’ suggesting that the country had opted to Remain – information which matched YouGov’s public poll, released at around the same time, and some private hedge fund polls. IT’S A CONSPIRACY: Our text exchange with Nigel Farage on Tuesday night

However, the Bloomberg story questions the possibility that Farage had also been told of polling suggesting Leave had in fact edged it, or at the minimum that it was too close to call. The publisher states that in an interview, Farage confirmed he was aware of a poll by Survation, which correctly predicted a Leave result, before making his public statements.

Farage is himself a former trader, and his apparent public concession – especially backed up with the statement that he had received information from the City – was always likely to lead to an increase in the pound on a major scale. On a regular day, a statement by Farage would be unlikely to move the pound much, if at all. But this was not a normal day, or night.

The Bloomberg investigation questions whether Farage, believing that Leave may have won, deliberately claimed otherwise to help maximise the profits that his friends in the City would make. The pound would climb for a few hours (as it did), until the first results came in and showed Leave was likely to win, which would then prompt it to plummet.

Farage has firmly denied any such suggestion, telling Bloomberg that his concessions were not aimed at moving the markets for anyone, and giving a statement to MailOnline that he did not try to mislead people by conceding defeat. ‘There were many conflicting opinions and supposed polls that night,’ he told the website. ‘My frame of mind was negative on balance until [the] Sunderland [vote was announced, and pointed towards a Leave victory].’

However, what might be particularly shocking is that even if Farage had knowingly and deliberately done that, there’s very little chance that it would actually be illegal.

Most of us have heard of the term ‘insider trading’, and the hypothesis outlined here might feel like it should be covered by that term. However, ‘insider trading’ is actually much more specific than that: it covers people working for publicly-traded companies, who are obliged to release their financial information to the public and all investors at the same time. If someone knows a company’s results will be terrible the next day and either sells or shorts the stocks, that’s insider trading.

For currency markets, it’s different – no-one knows exactly what is going to happen to them, so no-one is, strictly speaking, an insider trader. Even buying up the most expensive and accurate polling model known to modern political science is not the same as knowing the result in advance: we have all learned in quite some detail just how wrong polls can be in recent years.

There’s another law the hedge funds’ practice might cut across, but it’s a bit of an ambiguous one: it is not allowable in the UK to share information on how people might have voted while the polls are open with ‘any section of the public’. This is, incidentally, why no-one can publish the results of an exit poll until the voting ends at 10pm.

In theory, we might wonder whether commissioning a private poll and sharing it with a handful of traders at a hedge fund would amount to a breach of that law – surely a few traders amounts to a ‘section of the public’. The difficulty would be that in that case, the very act of trying to prepare a poll for 10pm – which needs sharing with various researchers – would likely fall foul of the law. Given it’s never been tested, it leaves us in a mess.

Farage is not the only politician with a previous link to the financial sector, nor the only one who has been accused of profiting from his own political positions. The influential Conservative backbencher – and arch-Brexiteer – Jacob Rees-Mogg is a former fund manager and is still an investing partner in one.

No-one has offered any evidence either Farage or Rees-Mogg, nor any other politician, has deliberately used their public position in this way to profit themselves or their friends, but the very possibility of it undermines public trust in politics, whether legal or otherwise. Just because a practice is legal doesn’t mean it’s right, or even acceptable.

The possibility for abuse inherent in this system is yet another way in which the UK electoral laws – and the laws governing the conduct of politicians – as they stand are not fit for purpose. We should be able to have faith that our elections are carried out freely, fairly, and without interference. We should be able to have faith that our politicians are acting on behalf of their constituents, or their own closely-held beliefs, rather than financial motives. We should have faith that hedge funds are making their profit from a playing field that, while viciously competitive, is fair.

Our current system of rules are not inspiring confidence in any of those things. It’s far past time to change them.