As Labour’s leadership hopefuls try to work out their position on freedom of movement, ZOE WILLIAMS looks back at the way immigration has been exploited as a political issue.

The issue of immigration shaped the discourse of the 2016 referendum – a fact which was swiftly denied by the victors, in a manoeuvre with which we have become dispiritingly familiar, swearing blind that day is night.

Yet it did seem to drop from the front of the nation’s consciousness over the ensuing years. Resistance to it, which hit a peak for modern times in 2015 – when 71% of British adults said too many immigrants had been allowed into the UK – declined (or “softened” as analysts often put it – I don’t think it is especially soft, to welcome the arrival of the foreign-born, in the spirit of the universal human drive for freedom, adventure, discovery, industry… but whatever, let’s call these attitudes “softened”).

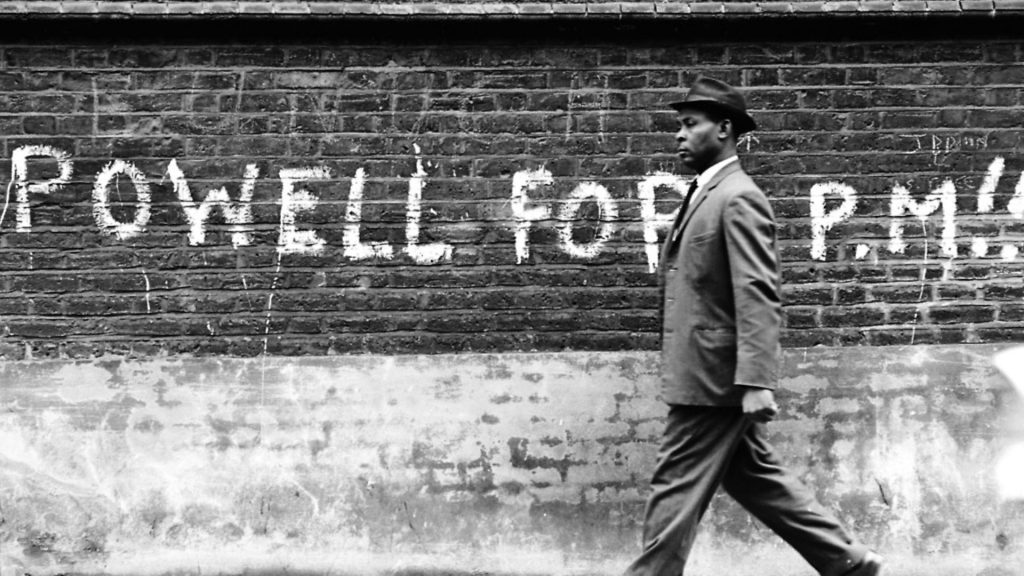

By 2018, according to the European Social Survey, that proportion had dropped to 26%. Plainly, a lot happened to attitudes between Enoch Powell’s memorable histrionics in 1968, and Britain’s counter-productive withdrawal from the world stage in 2020. But these happenings were not as simple as the often-cited cause, when Tony Blair waived Britain’s right to ‘transitional controls’, following the extension of the EU’s free movement zone in 2004.

Between 2007 and 2008, opposition to immigration – according to the same pollsters, Ipsos Mori – fell by nine points. By 2012 it was at a 20-year high. Political language makes a huge difference, especially the language of seemingly neutral participants.

This is why there was a furore this week about a report by the BBC’s Mark Easton, which is a good place to start for the broadest overview. After Powell, immigration was “barely discussed for three decades”, Easton contended. Maya Goodfellow’s book, Hostile Environment, dispatches this quite comprehensively: in 1971, the Immigration Act limited permanent migration from the Commonwealth, two years before migratory rights were conferred upon EU citizens as part of our joining (creating the implicitly racist system that actually Brexiters on the left and right have complained about).

In 1978, Thatcher built her political hegemony on (among other also unpleasant ideas, like “we’ve had enough of the softer virtues”) sympathy with Britons who might feel “rather swamped” by people of a different culture – language which was obliterated in the cosmopolitan 1990s but came back to the mainstream with a vengeance under David Cameron and his “swarms”.

In 1981, the British Nationality Act removed citizenship by birth (jus soli), and babies had to have one British parent to qualify: women could no longer become citizens just by dint of marrying a Briton. It’s fair to say that, over this period, we were talking about immigration almost constantly.

Yet attitudes were – as they say – softening, so that by 1997 the lowest proportion of Britons since records had begun thought there were too many immigrants (though this was still relatively high – 61%). This steady decline is not because mainstream conservatism changed its stance, but because there was a vigorous fight back from anti-racism movements, which did as much as anything to create the mood of optimism and inclusivity that swept Blair’s government into power.

There were moves made by New Labour that were plainly fixes devised for headlines, and were – by any objective reckoning – spiteful. It was Blair who decreed that asylum seekers could no longer work until their claims had been processed, casting scores of thousands of people in the years since into penury and powerlessness. And for what? To appease the tabloids, who at that point were fixated not on benefits cheats but on bogus asylum seekers.

The New Labour compact with the tabloid press was to disdain them for their hysterical and often overtly racist agenda, while at the same time trying to assuage that hysteria and racism with concrete policies, all the while making an essentially free market argument for the ‘good’ sort of immigration (that the definition of a successful country was when people wanted to come and live in it).

It was, in other words, not just morally vacuous but incredibly dumb. That element of the press can never be sated, and no government can convincingly deliver two messages – anti-racism to one audience, restricted rights for foreigners to another – without itself becoming shamefaced.

When Labour took on its mantra – we haven’t had the “honest conversation”, we’ve been silent too long – and Gordon Brown was torpedoed for shying away from an “honest conversation” (following his disastrous description of the “bigot woman” on the campaign trail), the root cause was dishonesty: but not in the way they meant, that we should all sit around talking about foreigners, which would culminate in some mugs that said “controls on immigration”. Rather, they were trying to ride two horses, social liberalism in one lane, xenophobia in the other, and one of those horses was not happy about that, and the other horse was actually a tiger.

These constraints remained in the Labour leadership for years – that mug (even if you opposed immigration, when would you ever drink that from a mug?) was Ed Miliband’s of course, and Corbyn characteristically flip-flopped. Lisa Nandy, making a trenchant case for free movement, underpinned by a commitment to investment in British jobs and skills, is the first Labour figure in years to break that zero-sum frame where you’re either with migrants, or with the ‘left-behind’ but you can’t be both.

When Michael Howard burst onto that scene, for the election of 2005, with posters that were laughably insinuating (“are you thinking what we’re thinking?”), he was taken as a joke: surely that agenda, too embarrassed to speak its own name (WE’RE THINKING, GO HOME, JOHNNY FOREIGNER), belonged to a completely different era, to the political posters of the 1960s, to a small-mindedness nobody can remember, or even cares to. And he bombed, of course – or at least, failed to make headway against a Labour government that in the immediate aftermath of the Iraq war was itself deeply unpopular.

So it seemed as though that dragon – the one that connects immigration to nationalism to discontent – had been very easily slain, lacking in power. But even though he never gets the credit, Howard had emboldened all the most aggressive elements of his own party. By the time they came to partial-power, the Conservatives were promising arbitrary reductions to migration, refining their hostile environment which would reclassify as illegals people who had lived here all their lives, operating as a nidus for the Islamophobia which isn’t the same conversation but frequently overlaps it, and making jolly racist japes in previously quality newspapers.

I never understood the traction this got with the wider population until well into the coalition government, talking to an extremely rich woman whose son had recently failed a bunch of exams for private schools, ending up not where his father went, nor his grandfather, but some godforsaken place that didn’t even begin with an E. “Walking into those examination halls,” she said, “it looks like f**king Beijing”.

Hostility to immigration isn’t really about prosperity or GDP; it doesn’t map well onto the numbers of migrants in any given area (indeed, there’s an inverse correlation, the more migrants there are, the happier people are with it; “we asked workers,” the novelist Max Frisch once wrote. “We got people instead”.)

It’s about civic space. When people feel they are being ejected from a civic space that belonged to them, they’ll resent anything, find an enemy anywhere, in a 10-year-old, in a headline, in a foreign accent, in an MP’s made-up anecdote.

During this period, from 2010 onwards, citizenship was conceived in an assertively new way – proper citizens were “hard-working”, people were divided into strivers and shirkers, net contributors and net recipients, measured by their productivity, castigated for claiming benefits. And all the liberal arguments in favour of migration – principally, that GDP was boosted by it – fell completely flat, because that was part of the problem.

People looked at a value system in which any given person with two jobs was worth more than anyone on 15 hours, and flat refused to live by it. This culminated in the failure of the Remain argument – stay in Europe because, one way or another, you’ll be richer. People weren’t sick of experts. They weren’t even sick of poverty (although that too). They were sick of their citizenship having a price tag. And with that energy, Nigel Farage, or a figure like him, could do almost anything.