The Dutch city might be better known for its art, but from its Golden Age to the present day music has been at the heart of its identity. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports.

Despite spending his whole life in his home city of Delft, 40 miles from Amsterdam, Vermeer is as synonymous with the capital of the Netherlands as he is with the Dutch Golden Age. The four Vermeers that hang in the city’s Rijksmuseum – three of his typical domestic scenes and the captivating The Little Street, showing Delft’s Vlamingstraat – are a major draw to the over two million visitors to the museum each year. In The Love Letter, the woman at the centre of the scene has been interrupted during playing her lute by her maid delivering the missive, and almost a third of Vermeer’s 34 known surviving works depict some kind of music-making.

While music was often used highly symbolically in the art of this period – to suggest harmony between individuals or with god, for example – such depictions nonetheless give tantalising glimpses of the role of music in Dutch culture and society in the century when mercantile wealth had made the Netherlands a world power, and several works in the Rijksmuseum, as well the 17th century instruments it displays, give a powerful sense of the musical life of Amsterdam four centuries ago.

While the economic success of Dutch merchants saw an explosion in patronage for visual art and a flowering of artistic genius, the situation for music was less clear cut. The Calvinist attitude to music meant it was excluded from services and became relegated to recitals in church, and the Dutch composers of the period were not innovators.

Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, for example – who spent nearly 45 years as organist at the city’s Oude Kirk and was dubbed ‘the Orpheus of Amsterdam’ for his organ music – continued to work in the Renaissance tradition when the Baroque was in full swing elsewhere.

It fell to those from outside the United Provinces of the Netherlands, like the Belgian composer Carolus Hacquart, to bring this ‘new’ style to the country. Hacquart worked as a music teacher in Amsterdam in the 1670s, ministering to the musical enthusiasts of it is bourgeoisie. While the Rijksmuseum’s portrait of composer and member of the Amsterdam-based intellectual circle the Muiderkring, Constantijn Huygens, is a reminder that original music was forthcoming from Amsterdam in this period, more low-key, domestic musical practice was perhaps the most important manifestation of music in the Dutch Golden Age. And this was shared by both high and low society.

The Rijksmuseum’s c. 1640 painting by Jan Miense Molenaer of a woman playing a virginal at home, as well as the portrait of the family of Amsterdam merchant David Leeuw – poignantly from 1671, just before the ‘Disaster Year’ of war and poverty that effectively killed Vermeer and impoverished merchants like Leeuw – which shows his children playing the harpsichord and the viola da gamba, are windows onto the musical life of Amsterdam’s Golden Age well-to-do.

But these genteel pursuits co-existed with the far rowdier affairs of the muziekherbergen (music taverns) of Amsterdam, where instruments hung on the wall ready for patrons to play. The tavern opened by one Johan Theunissen on Dam Square in 1604 was well-known, and popular song thrived in the Netherlands in this period, with songbooks like Oude en nieuwe hollantse boerenlieties en contredansen (‘Old and New Dutch Peasant Songs and Country Dances’), first published in Amsterdam in 1700, becoming wildly popular.

In the middle of the 20th century, Amsterdam continued to punch below its weight in terms of volume, if not quality, of composers, while soon making waves in popular song. The countercultural radicalism of the 1960s had been embraced with particular fervour by Dutch youth and music was one target for their revolutionary energies. The Concertgebouw Orchestra, founded in 1888 and based in the concert hall facing the Rijksmuseum across the vast Museumplein, was criticised for its conservatism, and malcontents once set off a hoard of wind-up frogs in the middle of a 1969 performance in protest at its staid programming.

Among those demonstrators was Amsterdam-born Louis Andriessen, who that same year had co-founded the radical Studio for Electro Instrumental Music (STEIM) in the city with fellow enfant terrible of the Dutch music scene, pianist Reinbert de Leeuw, and the Ukrainian-born adoptive Amsterdammer, free jazz pianist Misha Mengelberg, among others. Andriessen’s avant-garde ensemble Orkest De Volharding, formed in the city in 1972 and initially made up of a piano and three each of saxophones, trumpets and trombones, demonstrated his interest in unconventional instrumental combinations.

Andriessen’s probing of the relationship between music and the political that began with his activism in the 1960s continued into the next decade with his violently mechanical Workers Union of 1975 and the following year’s De Staat, a minimalist masterpiece which set Plato’s Republic to music. Andriessen’s later work dealt with the giants of Dutch art. De Stijl (1984-85) was inspired by Mondrian – alumnus of Amsterdam’s Royal Academy of Visual Arts whose works hang in both the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum – while his 1999 opera Writing to Vermeer, premiered by the Dutch National Opera in the city, was based on some of the real historical events from Vermeer’s life.

As Andriessen was entering his mature period, other, more popular, impulses were coming out of Amsterdam. Prog band Focus were founded in 1969 by two Amsterdam natives – guitar virtuoso Jan Akkerman and classically-trained flautist Thijs van Leer. From a musical, bohemian family and schooled in jazz and classical, frontman van Leer’s influences were ripe for prog experimentation and Focus became the biggest Dutch musical export of the period.

In February 1973 their Hocus Pocus and Sylvia – both featuring van Leer’s unmistakable vocals, which included yodelling and falsetto vocal gymnastics – peaked at UK No.20 and No.4, respectively, in the same week. Hocus Pocus also entered the US Top 10, and manic performances on NBC’s Midnight Special and the Old Grey Whistle Test sealed their reputation as one of rock’s true originals.

Amsterdam exports have continued to trouble the international charts. The Van Halen brothers were born in the city in the 1950s, moving to the US as small children. They were welcomed as heroes when they played the Amsterdam Paradiso during their first world tour in 1978, but their 1995 song Amsterdam was, bizarrely, written from the outsider perspective of singer Sammy Hagar and focussed almost solely on the city’s cannabis cafes and brothels (“Oo, wham bam/ Oh Amsterdam!/ Stone you like nothing else can”).

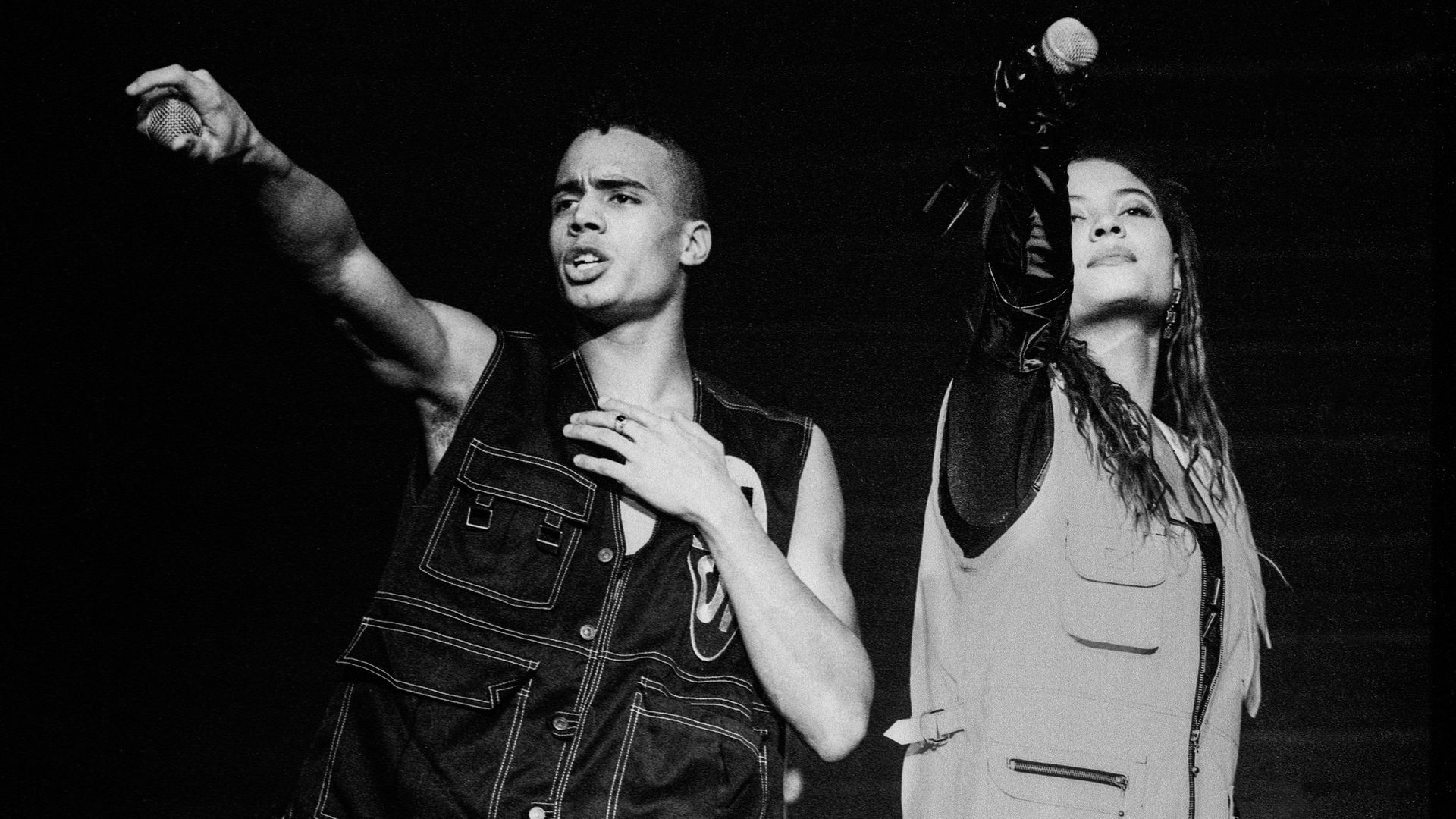

As Eurodance duo 2 Unlimited, Amsterdammers Ray Slijngaard and Anita Doth had a global No.1 in 1993 with the insistently repetitive No Limit at a time when the Netherlands had become a global force in dance music. More recently, baby-faced superstar DJ Martin Garrix, born Martijn Garritsen in the Amsterdam suburb of Amstelveen in 1996, has become a house music titan, bringing the sound of Amsterdam’s hedonistic nightlife to the world.

But the outsider’s image of Amsterdam remains something between Jacques Brel’s Amsterdam (1964), a devastatingly bitter portrait of the city’s seedy alleys and dissolute lives, and the chocolate-boxy cheerfulness of the city’s own levenslied singer Johnny Jordaan’s Geef mij maar Amsterdam (1955), which speaks of a city “That’s more beautiful than Paris”. As in Vermeer’s time, Amsterdam remains a city where the beautiful and the base coexist.

TULIPS, WINDMILLS AND DETECTIVES

The Dutch capital has been a popular theme on the UK pop charts. Tulips From Amsterdam was originally intended as a German schlager song before being recorded in Dutch by Belgian singer Jean Walter and becoming a No.3 hit for Max Bygraves in 1958. Ronnie Hilton’s 1965 novelty song A Windmill In Old Amsterdam, about “a little mouse with clogs on”, was his final hit. In the autumn of 1973, the theme tune to Amsterdam-set detective drama Van der Valk, Eye Level, written by Amsterdam-born composer Jan Stoeckart, occupied the UK No.1 spot for four weeks.