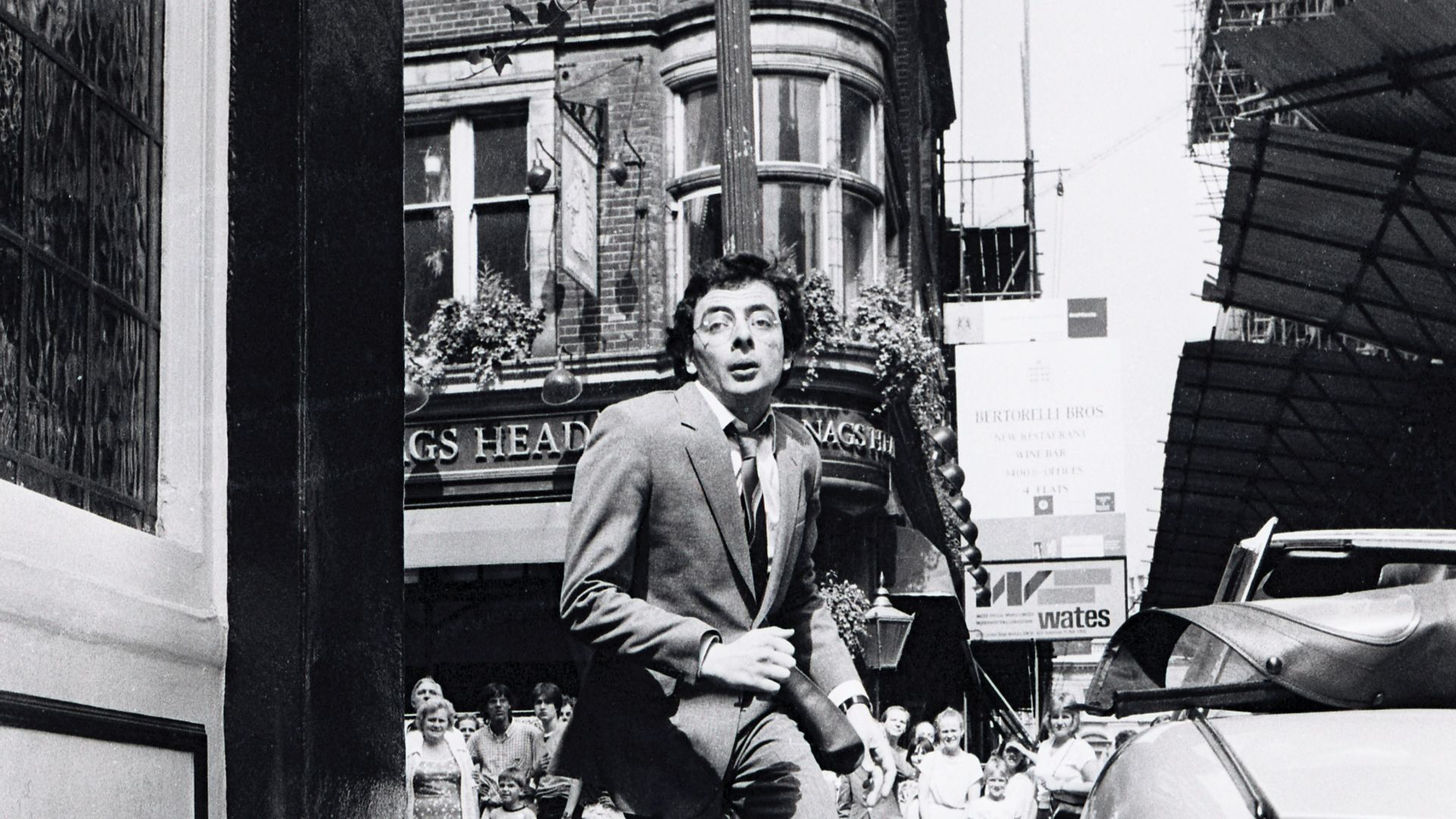

TIM WALKER remembers a meeting with a particularly pensive Rowan Atkinson

I met Rowan Atkinson on an autumn day in 1988 that, he informed me, was the 10th anniversary of the start of his career in show business. Up until that point, his credits included the ground-breaking satirical television series Not the Nine 0’Cock News, Blackadder and its sequels, a couple of solo revues in the West End and on Broadway, the lead in Larry Shue’s play The Nerd, and a cameo in the unofficial James Bond entry, Never Say Never Again.

Atkinson was then trying to gain acceptance as a serious actor in a production of the Chekhov classic The Sneeze, with Timothy West as his co-star. He had been rehearsing in a small hall in Chelsea, just across from the Thames, and we’d found a bench in a park to sit on. He was then 33, nervous, awkward and unable to engage in eye contact. I’d hoped he’d make me laugh when we met, but he didn’t, not once. “People think because I can make them laugh on the stage, I’ll be able to make them laugh in person,” he explained, apologetically. “That isn’t the case at all. I’m essentially a rather quiet, dull person, who just happens to be a performer.”

Entertaining the masses was a skill that seemed to come effortlessly to him, but gaining approval in more highbrow circles was proving elusive. Frank Rich, the powerful New York Times critic, had said in a review that Atkinson couldn’t seem to progress beyond “toilet humour” and his act was based on an English schoolboy “obsession with alimentary products”. Atkinson’s days at a minor public school on the Cumbrian coast had actually passed by unremarkably. Quite academic, no good at games, certainly not the sort of embryonic comedian who’d regale his classmates with funny stories. He’d emerged, he said, “with no hang-ups” of the kind that had troubled Rich. The assumption was that he’d become an electrical engineer as it was for that he’d been training.

“I never had a driving ambition to perform, but, when I got to Oxford, there was an ad in the news sheet for the dramatic society and I just thought I’d give it a go. I’d always enjoyed acting in school plays, but never thought of it as a career. I guess I would probably be with some am dram group now – and I’m sure quite happy – if the right people hadn’t taken an interest in me.”

As things started to progress, he fretted about how his mother might take it. The family were staunch Conservatives and his two older brothers had started in “sensible jobs” in the City and working for a big company. “I think my mother thought show business was full of bouncing cheques and homosexuals and people in nasty bow ties,” he said. “I tried to reassure her by getting a really well-dressed, middle-class agent who looked like a bank manager.”

His first major television appearance was in a pilot show for London Weekend Television called Canned Laugher, in which he was such a success he was offered his own series. He turned it down, however, feeling that he wasn’t quite ready. Later, when he was appearing on Not the Nine 0’Clock News, he was still not especially ambitious, feeling, as he put it, “strangely apathetic” to what was going on around him.

For all that, he was provoking strong reactions. The Guardian startlingly called him a “w*****” in print, which upset him. “Then I found myself reading what some pop star loved and hated – it was one of those silly lists they do in newspapers – and my name appeared under the latter heading. I remember being very struck at the time that a man I had never met actually hated me. It was rather frightening.”

The characters the early Atkinson liked to portray were almost always flawed and unhappy individuals – an angry bigot in the raincoat, a closeted gay vicar, a duplicitous politician, an impatient man in a queue – but all of them, he insisted, were “bizarre figments” of his imagination, and no more. Atkinson didn’t seem to like where I was going with this line of questioning and said he had to get back to rehearsals. We kept talking as he headed to the hall and I asked him finally if he was happy. He stopped, thought for a moment, and then replied: “Yes… I think I am. I hope people will give me credit, however, for being more than just a face-puller.”