English music takes a radical turn which continues to resonate three centuries on – SOPHIA DEBOICK reports.

After more than six years of civil war, the fabric of British society had been riven and the system of government dismembered by 1649. Religious certainties had crumbled as old power structures were torn down. In Scotland there was religious hysteria as radical Presbyterianism took the reins of power and the Witchcraft Act of 1649 opened the floodgates of persecution.

In England, meanwhile, revolution brought an atmosphere of religious tolerance in which radicalism flourished. New, if short-lived movements arose, predicated on ideas of political equality and social and economic reform, and strange new creatures – Diggers, Levellers and Ranters – appeared. Like others throughout history, mid-17th century people negotiated these turbulent times through song, but this time of radicalism and revolution also had lasting effects on the imaginations of the songwriters of these islands, its events memorialised in song for years after and vividly linked to modern concerns in folk, protest song and rock three centuries on.

A coup d’etat of the previous December, Pride’s Purge, saw the removal from parliament of those members alarmed by the radicalism brewing in the New Model Army and by January 1649 the stage was set for the final, irrevocable elimination of the king – via the scaffold at Whitehall.

The declaration of the Commonwealth and the conquest of Ireland would follow, and the simple binaries of Cavalier and Roundhead were superseded by new allegiances as the Cromwellian regime proved itself to be far from the promised ideologically pure project. Popular ballads of that year – printed as one-page broadsides that were sold on the streets for a penny – found people trying to make sense of their new circumstances.

A Coffin for King Charles, A Crown for Cromwell found Cromwell declaring that he would ‘graspe the Septer, weare the Crown’, while Charles responded that his ‘sparkling fame and Royall Name’ would not die, and the people lamented their lot under the new regime, where ‘the Lawes are taken cleane away/ or shrunke to Traytors votes’.

The Royal Health to the Rising Sun expressed a wish for Charles’s son’s immediate installation on the throne (‘The sun [son] that sets may after rise again’), and expressed regret at the turn of events: ‘Let us cheer up each other then/ And show ourselves true Englishmen/ And not like bloody Wolves and Bears/ As we have been these many years’. But those of a more radical mind were taking the opportunity to forge a new world amidst the ashes of the old one, immortalising their ambitions in song.

The rapid rise and fall of the Diggers between early 1649 and the middle of the following year belied their significance for the English radical tradition. The movement’s founding father, Gerrard Winstanley, held that ‘True freedom lies where a man receives his nourishment and preservation, and that is in the use of the earth’, and the Diggers’ agrarian socialist vision was becoming a reality by April 1649 as Winstanley and his associates established an egalitarian, communal farming community on common land at St George’s Hill, Weybridge.

From there Winstanley issued the Diggers’ ultimate manifesto, proclaiming their aims of ‘working together in righteousness, and eating the blessings of the Earth in peace’. But for a rallying cry for the movement, he turned to song, writing the Diggers’ Song, which entreated ‘You noble Diggers all, stand up now, stand up now’. Despite being rooted in a fleeting, feverish historical moment, the song’s railing against establishment figures – priests, lawyers and gentry – and proclamation that ‘the gentry must come down and the poor shall wear the crown’ has appealed to generations of leftists ever since.

Anarcho-punks Chumbawamba would record the Diggers’ Song on their English Rebel Songs 1381-1914 of 1988, while 1960s folk revivalist Leon Rosselson recorded it as You Noble Diggers All a decade later. But the song had also inspired Rosselson’s own composition, The World Turned Upside Down, which told the story of the St George’s Hill commune, and was written in 1975, the same year director Kevin Brownlow’s painstakingly historically accurate biopic Winstanley appeared. That song would launch the career of Britain’s foremost latter-day protest singer, Billy Bragg, who included it on his chart debut – his Between the Wars EP, which reached No.15 on the singles charts in March 1985, at another moment of crisis for England, just as the miners’ strike was ending. While the St George’s Hill commune didn’t last the year, attacked by local landowners and besmirched by accusations of being members of the famously ‘immoral’ Ranter sect, the movement made an indelible mark on the English imagination – as Rosselson’s song put it: ‘They were dispersed/ But still the vision lingers on.’

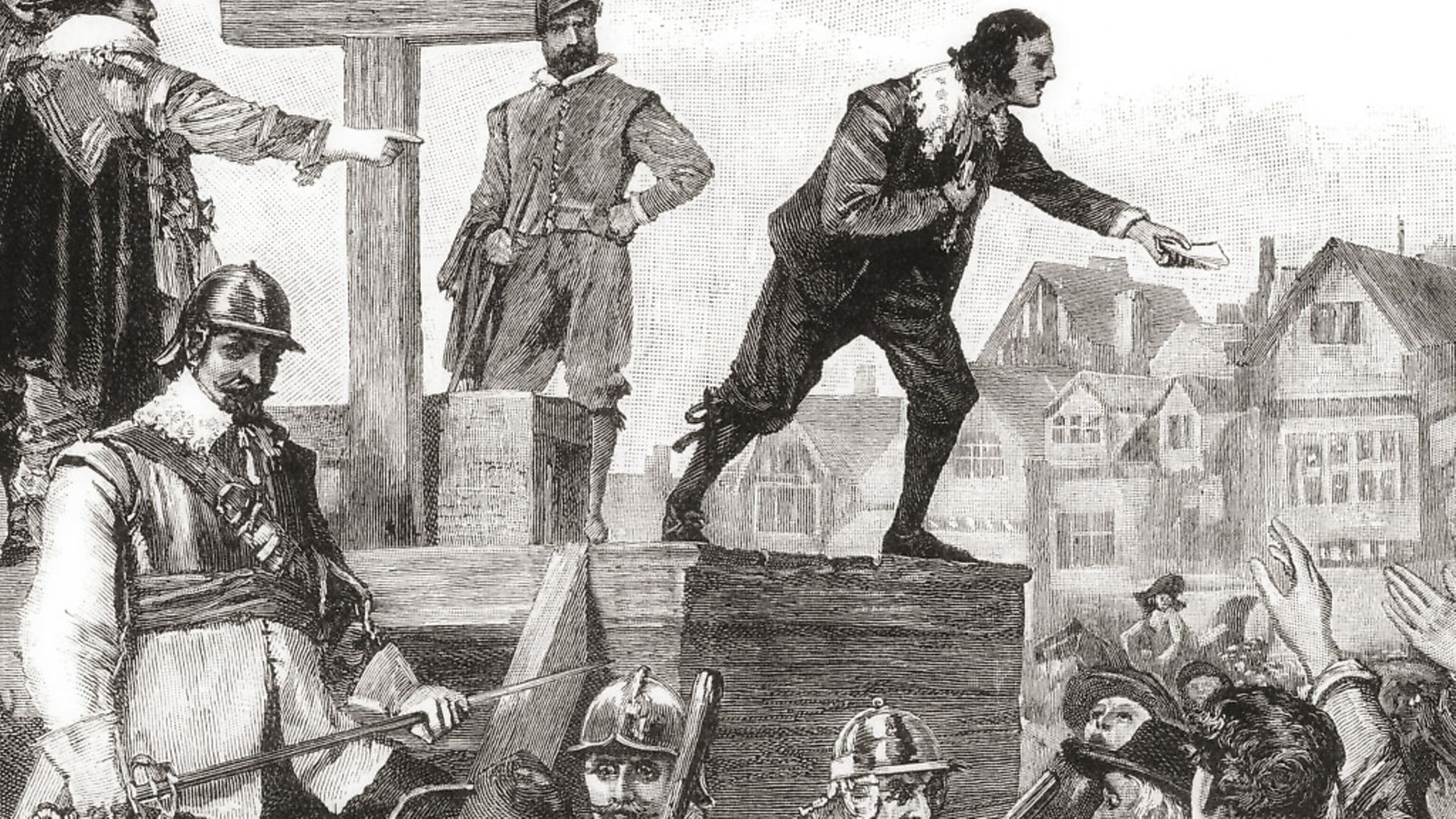

Winstanley had called his movement that of the True Levellers, distinguishing it from the rival group whose vision of political equality through popular sovereignty was, he felt, a limited one. The Levellers may have been less radical than the Diggers, but by 1649 they had succeeded in making the idea of inalienable rights – ‘freeborn rights’, as founding figure John Lilburne put it – a viable political concept, and the final instalment of their pamphlet, Agreement of the People, which expanded on the notion of natural rights, was published in May 1649. But the regime was waiting to stifle this movement they perceived as a threat, and days later, fearing the betrayal of the principles they had fought for, Leveller members of the New Model Army at Banbury staged a mutiny, were ambushed and their leaders executed. The Levellers’ power base was destroyed and in October Lilburne himself was put on trial for high treason. Despite his acquittal, the movement had been effectively killed off.

The image of the Levellers as principled but betrayed heroes has drawn left-wing bands to their legend. Brighton’s The Levellers would adopt the movement’s name and channel their values. Their Battle of the Beanfield ruminated on 1985 as a crisis point, just as Bragg’s EP had, decrying the violence meted out by the authorities in the clash between New Age Travellers and riot police near Stonehenge in the summer of that year.

The song had the narrative form of an early modern ballad and focussed on the essential right to live as one chooses, saying ‘It seems they were committing treason/ By trying to live on the road’ and angrily exclaiming ‘Hey, hey, can’t you see?/ There’s nothing here that you can call free’. Folk-punk band and sometime Levellers support act Ferocious Dog’s Freeborn John, meanwhile, told the story of the Levellers’ downfall: ‘Parliament promised changes, we fought against the king/ In the end when the war was won it didn’t change a thing.’

The conquest of Ireland – beginning when Cromwell landed in Dublin in August 1649 – is the root of an even greater sense of injustice which has been preserved in Irish folk memory and folk song. Cromwell’s attempt to break the Irish-royalist alliance and quell ‘the barbarous and bloodthirsty Irish’ once and for all began with in Drogheda in early September. Having breached the town’s walls, 6,000 troops swamped the town and massacred its inhabitants, even immolating civilians sheltering in a church. A month later, 1,500 non-combatants were massacred in Wexford while the town’s surrender was still being negotiated. Two hundred years later, Young Irelander and poet Michael Joseph Barry wrote The Wexford Massacre, a visceral retelling of the event which struck a vengeful note (‘And guiltless blood to Heaven will mount/ And Heaven avenge it, too!’). The poem has since been set to a traditional-style folk song, while Cromwell’s name has been taken in vain by many musicians of Irish descent, from Morrissey on 2004’s Irish Blood, English Heart, to The Pogues on Young Ned of the Hill, and Elvis Costello on Oliver’s Army, which conflated the British forces in 1970s Belfast with the New Model Army of 300 years before.

Revived during the Restoration, royalist ballads like When the King Enjoys His Own Again and The World Turned Upside Down (not to be confused with the Rosselson song) – a lament about the Puritan assault on Christmas (‘Holy days are despised, new fashions are devised/ Old Christmas is kicked out of town’) – enjoyed some longevity. But it is the tradition of English radicalism of 1649 that has lived on in music, speaking to contemporary concerns about the corruption of government and the erosion of freedoms over the last three decades and, no doubt, beyond.