As the Second World War took shape, a big band leader dominated the year. While, from very different quarters, a Disney film and an emerging folk star signalled sounds of the future.SOPHIA DEBOICK reports.

The year began with a sense of foreboding. Four months on from the Nazi invasion of Poland, Britain faced the start of a new decade in the midst of the Phoney War, as both sides kept their powder dry. But the freezing conditions and imposition of rationing in January was an ominous sign of hardships to come. Meanwhile, Poland itself faced atrocity at the hands of both occupying forces that had bisected the country, as the Soviets attempted to wipe out the Polish officer class and intelligentsia in March’s Katyn massacre and Polish political prisoners became the first inmates of Auschwitz in June.

But with the Nazi invasion of France and the Low Countries, suddenly the war became a reality for Britain, and it stood alone against imminent threat of invasion. The occupation of the Channel Islands from the end of June put Nazi jackboots on British soil, and while the Herculean courage of the RAF saw off the Luftwaffe in that summer’s Battle of Britain, the Blitz began in September.

German bombers would eventually claim more than 40,000 civilian lives in their attempt to force the country into capitulation. But as the soundtrack to these terrifying times came from across the Atlantic, where peace still reigned, music continued to innovate unabated. This was the year that Disney became a musical as well as a cinematic force, and the crooner and the swing sound reigned supreme, while a champion of the folk tradition emerged who was a world away from big band glamour, but would have untold relevance for musical history.

Glenn Miller had broken through just the previous year, as the achingly romantic Moonlight Serenade became the song of the summer of 1939. On August 1 that year, exactly a month before the invasion of Poland, he had recorded a song that came to define both the golden era of swing and the tumultuous wartime period to come.

In the Mood spent 12 weeks at No.1 on the Billboard Jukebox Record Buying Guide from October 1939 and topped pop charts well into 1940. It was not a wholly original song and as such was proof of Miller’s genius as an arranger, as he re-purposed a central riff that had existed for nearly a decade, first as one-armed trumpeter Joe ‘Wingy’ Manone’s Tar Paper Stomp, and then as Fletcher ‘Smack’ Henderson’s Hot and Anxious. Miller’s version was slick and tight, bombastic by virtue of the blaring sax intro, and topped off with a dramatic fade-away section at the end.

It became a million-seller, and even if it made Miller only a paltry $175 – RCA Victor’s no-royalty flat fee – he released almost 30 records that year, among them the No.2 singles Careless, A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square and Blueberry Hill, and No. 1 hits Tuxedo Junction and The Woodpecker Song, and was hugely in demand for live performance. 1940 was indisputably his year, marking the start of a career that burned brightly but briefly before he joined up to serve with the Army Air Forces Band in 1942. Two years later, while he was travelling to entertain US troops in France, his aircraft disappeared over the Channel in bad weather.

In the Mood was obscenely carefree in the context of a European conflict that had just got serious, but with the song, and with Moonlight Serenade, Miller recorded music that spoke to the popular imagination at a time when reality was grim and escapism was essential, and which became synonymous with the war years.

Other American bandleaders couldn’t touch Miller’s longevity, but they, along with the great crooners of the era, were major commercial forces in 1940 itself. Among the biggest hits of the year were Frank Sinatra with the Tommy Dorsey Band with I’ll Never Smile Again – the first No.1 to appear on the new Billboard national popular music chart that launched in July – and Bing Crosby’s Only Forever, the theme to the Billy Wilder-written comedy Crosby starred in that year, Rhythm on the River, which spent nine weeks at No.1 from October.

Crosby released almost 20 records that year, while Tommy Dorsey had already enjoyed chart success earlier in the year with Jack Leonard, who was replaced by Sinatra when he left the band to complete military service and had sung on the hits All the Things You Are and Indian Summer. Dorsey’s version of Benny Goodman’s No.1 hit Darn That Dream had also gone Top 20.

But big hits were also coming from some unlikely quarters in this year. Pinocchio was only Disney’s second feature film, yet it established the company’s knack for producing film songs that had chart potential when When You Wish Upon a Star became one of the best-selling singles of the year. Sung by vaudeville star and the voice as Jiminy Cricket in the film, Cliff Edwards – known as Ukulele Ike – it went on to be recorded by Glenn Miller later in the year to No.2 success, won Best Original Song at the following year’s Oscars (hot on the heels of 1940’s peerless winner Over the Rainbow) and would become Disney’s trademark tune.

In the context of the times, it was unbearably wistful, but it later gained some unusual significances. In the Nordic countries it is considered a Christmas song due to the traditional Christmas Eve airing of a 1958 Disney special featuring it, and as a jazz standard it has been recorded by everyone from Sun Ra to Dave Brubeck.

Disney’s other big film of 1940, Fantasia, would also have far-reaching consequences. The first film to be released in stereophonic sound, the cinema experience would never be the same again, and its classical soundtrack put Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice front and centre in the popular consciousness. Disney’s harnessing of music was a key part of its journey to becoming more than an animation studio, but a multimedia mass pop-culture phenomenon.

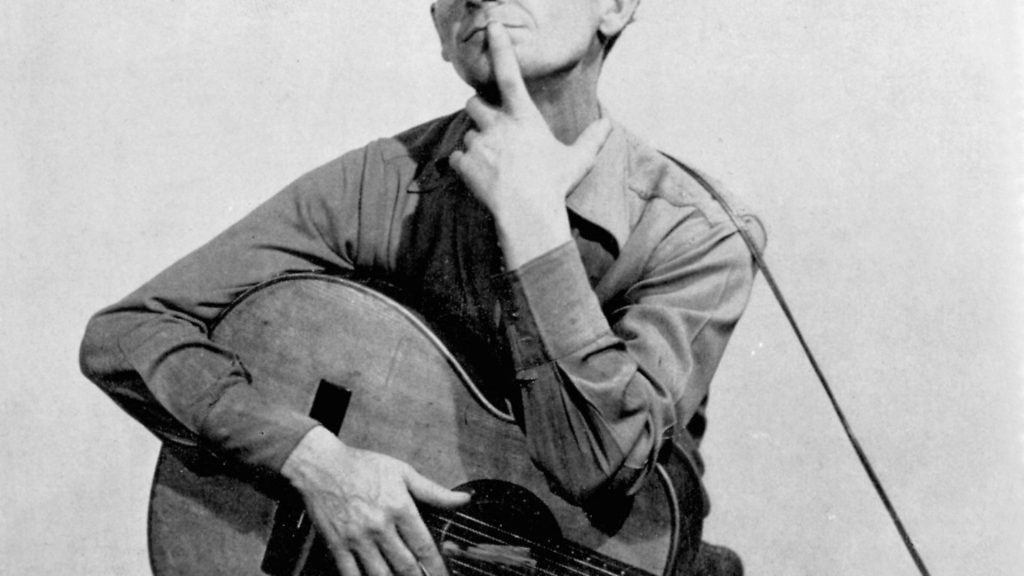

It was by way of a very different type of film that folk legend Woody Guthrie emerged onto the scene in 1940. The cinematic version of John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath (1939) was released in January 1940 and Guthrie’s debut album of July, Dust Bowl Ballads – one of the first concept albums – was a direct attempt to produce a companion piece to that tale of southern tenant farmers driven west by the grinding poverty of the Great Depression. (The two-part song Tom Joad transposed the book’s entire plot into a ballad.)

Although not of farming stock, Guthrie had made that westward journey himself in 1937, leaving his young family behind in Texas, to find work in California. February 1940 found him arriving in a snowy Manhattan having hitch-hiked across the country, a journey that inspired part of his hymn-like cry for egalitarianism, This Land is Your Land, that he would write shortly afterwards: ‘This land is your land, this land is my land/ From California to the New York Island/ From the Redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters/ This land was made for you and me.’

Guthrie’s birth as an artist could be precisely dated to the evening of March 3, 1940 when he performed at a benefit for the John Steinbeck Committee for Agricultural Workers organised by actor and social activist Will Geer (later to be well-known as Grandpa Walton).

There Guthrie met legendary bluesman Lead Belly, Alan Lomax, archivist at the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song, his then assistant Pete Seeger and the future director of Rebel Without A Cause, Nicholas Ray.

This was a meeting of kindred spirits, and Guthrie would feature on Lomax and Ray’s CBS radio folk show throughout the rest of the year. Lomax would also tap Guthrie’s folk knowledge, recording four hours of his songs and stories for the archive and, crucially, negotiating with Victor Records to get Dust Bowl Ballads made. In his foreword to Hard Hitting Songs for Hard-Hit People, Lomax’s collection of American folk songs, Steinbeck himself wrote of Guthrie: ‘Harsh voiced and nasal, his guitar hanging like a tire iron on a rusty rim, there is nothing sweet about Woody, and there is nothing sweet about the songs he sings. But there is something more important for those who will listen. There is the will of the people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.’

As the foundational touchstone of American folk – there would have been no Bob Dylan without Guthrie – and a formative influence for British rock ‘n’ roll, some of whose key protagonists, including Cliff Richard, Adam Faith, John Lennon and Ringo Starr, were born in 1940, Guthrie’s legacy is difficult to overstate.

In 1940 the full horrors of the conflict that had just begun still lay ahead, but in those wartime years music would prove its power as a force for salvation. Even as musical expression was suppressed under the European dictatorships, in a US at war the buoyant big band sound continued to thrive, Frank Sinatra went on to become one of the first teen idols, and the modern musical was born. And all these developments could be glimpsed in 1940 itself, a year when imagination and artistry was undimmed by the exigencies of war.