A dominant, if unconventional, Irving Berlin was confounding the critics, as music took its first tentative steps towards ‘pop’. SOPHIA DEBOICK reports

Progress was the watchword of 1913. The US was at the vanguard, with the opening of the world’s biggest railway station (New York’s Grand Central Terminal), and the world’s tallest building (the Woolworth Building), along with the dedication of the more than 3,000-mile coast-to-coast Lincoln Highway happening that year.

Ford were busy implementing the moving assembly line system just as great leaps were being made in aviation. While this spirit of accelerated advancement had seen its wings clipped the previous year in events that continued to hang heavy over 1913 – news of the ultimate failure of the Scott polar expedition broke in February and the papers continued to be filled with Titanic-related gossip as several survivors became celebrities – the soundtrack of the year strove towards the modern. New paradigms were emerging, and not just because the word ‘jazz’ first appeared in print that year. Pop as we know it was in development, providing the mass cultural backdrop to a rapidly changing world.

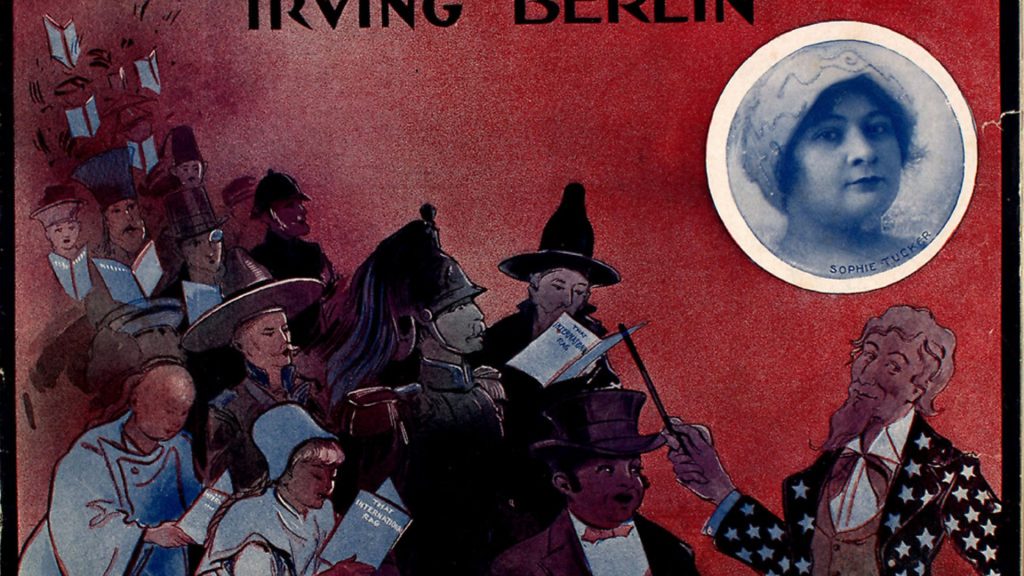

In 1911 Irving Berlin had created a new idiom for the pop song with Alexander’s Ragtime Band, but two years on, the success of that song and its associated dance craze still had not shifted public opinion towards new ideas of what popular music could be, at least not in Britain. When Berlin came to London to appear in person in his revue Hullo, Ragtime! in July, then seven months into a 451-performance run at the Hippodrome, he brought all the brash American imperative to self-promotion with him, calling a press conference and claiming he could compose a new song on the spot. His admission that he couldn’t read or write music and his use of his assistant, pianist Cliff Hess, as an amanuensis – to put his musical notes to paper – saw him denounced as a talentless con man in the press.

As opening night loomed, Berlin’s nerves grew on realising that the British public knew his back catalogue already and would be expecting something new when he took to the stage. The night before his appearance, he and Hess – already used to pulling intense all-nighters as Berlin’s live-in musical scribe – wrote That International Rag in their room at the Savoy. The critics had to eat their words as Berlin gave a beautifully nuanced vocal performance of the song at its debut, The Times review saying: ‘He sings his rag-time songs with diffidence, skill and charm. In his mouth they become something very different from the blatant bellowings that we are used to.’

While in London, Berlin also performed his new song, When I Lost You, which portly Canadian singer Henry Burr had made a hit earlier in the year (his Last Night Was the End of the World, written by songwriting duo Harry Von Tilzer and Andrew B. Sterling, was another doleful hit of that year). The song was a moving tribute to Berlin’s wife, Dorothy Goetz, sister of his collaborator Ray Goetz, who had died the previous summer, less than six months after their marriage, having contracted typhoid during their honeymoon in Cuba. The song was Berlin’s first ballad, and its depth of feeling (‘The birds ceased their song/ Right turned to wrong/ Sweetheart, when I lost you’) proved that in writing as well as delivery he was more than just a pop foot-tapper, and it would go on to become a crooner’s standard.

Belarussian-born Berlin was a dominant force in New York’s Tin Pan Alley, the world’s music publishing and songwriting powerhouse. It was dominated by immigrant talent and he was not alone in forging a new sense of the popular. The sensation of the year was You Made Me Love You (I Didn’t Want to Do It), a collaboration between Italian-born composer James V. Monaco and American lyricist Joseph McCarthy. Lithuanian Jew Al Jolson, increasingly a name to conjure with on Broadway, featured the song in his revue The Honeymoon Express that year, and his June recording of the song for Columbia sent it stratospheric. Its repetition of the subtitle sounded particularly modern and it would be recorded by countless other artists in the coming years – it took on a particularly plaintive quality when it was sung with breathtaking feeling and skill by a 14-year-old Judy Garland in the film Broadway Melody of 1938.

Peg o’ My Heart, meanwhile, was another collaboration between immigrant and native songwriters – Alfred Bryan and German-born Fred Fischer – and, like Jolson’s hit of that year, it also got its initial fame on the Broadway stage, being featured in the 1913 Ziegfeld Follies at the New Amsterdam Theatre. Recorded by Henry Burr for Columbia, and tenors Charles W. Harrison and Walter Van Brunt for Victor and Edison, respectively, during the course of 1913, it became one of the runaway hits of the year.

However durable such songs may have proven into Hollywood’s golden age, in this year Tin Pan Alley proved itself capable of producing a song that has come to be regarded as a quasi-sacred standard that existed outside the limits of historical time. When Irish Eyes Are Smiling came off like an ancient folk ballad from the Emerald Isle itself, but it was the result of a collaboration between native New Yorker George Graff and Ohioan Ernest Ball, both professional songwriters, and vaudeville performer Chauncey Olcott. Olcott was born in Buffalo, New York, but claimed Irish ancestry, his mother having been from County Cork.

Featured in the short-lived musical The Isle O’ Dreams, which only racked up 32 performances at New York’s Grand Opera House in early 1913 before it closed, When Irish Eyes Are Smiling was little-noticed, but in February, Olcott himself made the first recording of the song and it took off in a major way. The inflection of his semi-operatic delivery betrayed his American background, but given the huge Irish immigrant population of the time and the attendant market for music to appeal to that demographic, the song could not fail, and Irish tenor John McCormack would go on to make a celebrated recording of the song during the First World War. In exalting fortitude and optimism in the face of adversity, and marking the Irish out as a chosen race (‘When Irish hearts are happy all the world seems bright and gay’), it became an anthem for the Irish diaspora.

In Europe, more radical sounds could be heard. The May premiere of the Ballets Russes’ The Rite of Spring, scored by Stravinsky and choreographed by Nijinsky, was attended by a who’s who of the cutting edge of French culture, from Coco Chanel to Marcel Duchamp and Maurice Ravel, and so avant-garde was the content that the audience threatened a riot. Already, that March, Schoenberg had provoked a similar reaction at a performance of the Vienna Concert Society, which had deteriorated into physical violence. For Britain’s part, it was political rather than artistic provocation that defined the year.

The suffragettes’ campaign of militancy was at its height in 1913 with both Emmeline Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), characterised by its motto ‘deeds not words’, and Millicent Garrett Fawcett’s non-militant National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), engaging in frenetic activity. Imprisoned for the bombing of David Lloyd George’s Pinfold Manor in February, one of 250 cases of criminal damage that year, Emmeline Pankhurst sang Ethel Smyth’s The March of the Women, a song that had been adopted as the WSPU’s official anthem in early 1911, to keep her spirits up as she undertook yet another hunger strike. Emily Davison being trampled by the king’s horse at the Epsom Derby in June and the six-week march to London and rally of 50,000 people in Hyde Park organised by the NUWSS in July were very different events which nonetheless marked the culmination of the struggle.

The suffragettes would see the achievement of their aims only after the coming war, and events in 1913 foreshadowed major geopolitical changes to come. War in the Balkans would culminate in the assassination of the Austrian heir-apparent by a Serb in Sarajevo in June 1914 and the sparking of the First World War itself. Discontent in Ireland throughout the course of 1913 showed the tensions that would lead to the partition of 1920. And while Stalin was in exile in Siberia in 1913 as the House of Romanov celebrated the 300th anniversary of its succession to the Russian throne, revolution in Russia was less than half a decade away.

Pop music would be used for both good and ill in the conflicts to come, but the years immediately preceding 1914 had been crucial in the development of a truly popular music.