Fifty years ago, the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission managed to turn a technical failure into a stunning success. But, in the longer term did NASA come out stronger or weaker? MICK O’HARE reports

Although Jack Swigert never actually said ‘Houston, we have a problem’ the words have since passed into the canon of English cliché, shorthand for an unexpected complication or mishap. Nonetheless, when his voice crackled into Mission Control, he sounded – as his training had taught him to be – appreciably calm. Yet his real words – ‘OK, Houston, we’ve had a problem here’ – were an enormous understatement because, boy, did the three astronauts of Apollo 13 have a problem. Swigert, along with Fred Haise and mission commander Jim Lovell were likely to be dead within hours as their oxygen seeped away into space.

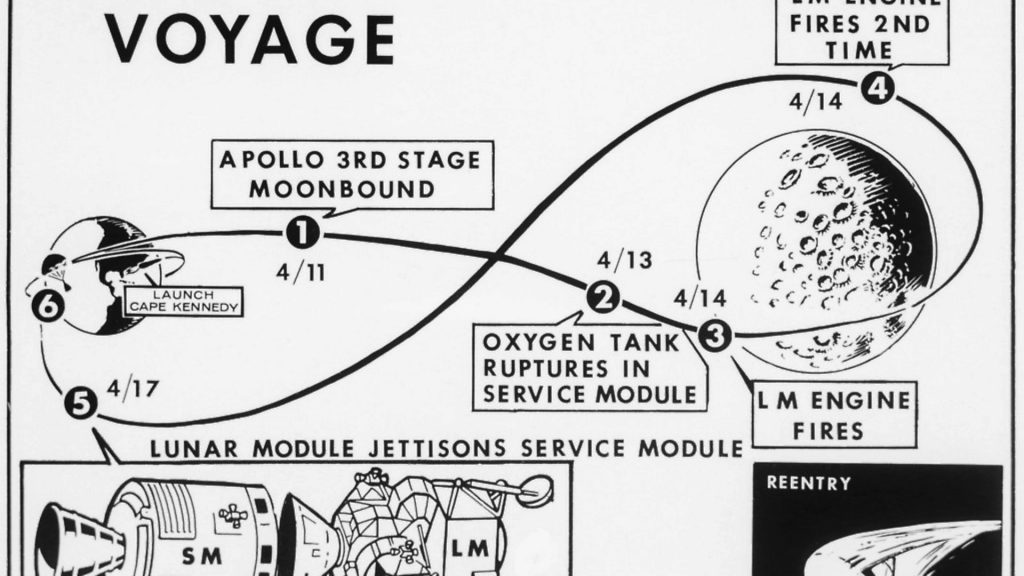

Three days earlier, Apollo 13 had lifted off from the Kennedy Space Centre on April 11, 1970 on what was already becoming a ‘routine’ mission: flying to the moon and back.

The public barely registered the fact that somebody else would soon be walking on the lunar surface. After all, four men already had. Fifty-six hours later everybody on the planet who had a TV or a radio was tuning in.

During a routine stirring of one of the Command Module’s oxygen tanks the astronauts heard a loud bang, felt the spacecraft shudder and an internal wall flexed. Damaged insulation had left exposed wires in the tank. When the switch to stir it had been flipped, the wires had short-circuited, sparking an explosion.

Lovell looked out of the window and told Mission Control that a gas or liquid was venting into space. It was oxygen. Their life support was bleeding away into the void. Two of their three fuel cells were dead too and oxygen was also needed to power the spacecraft.

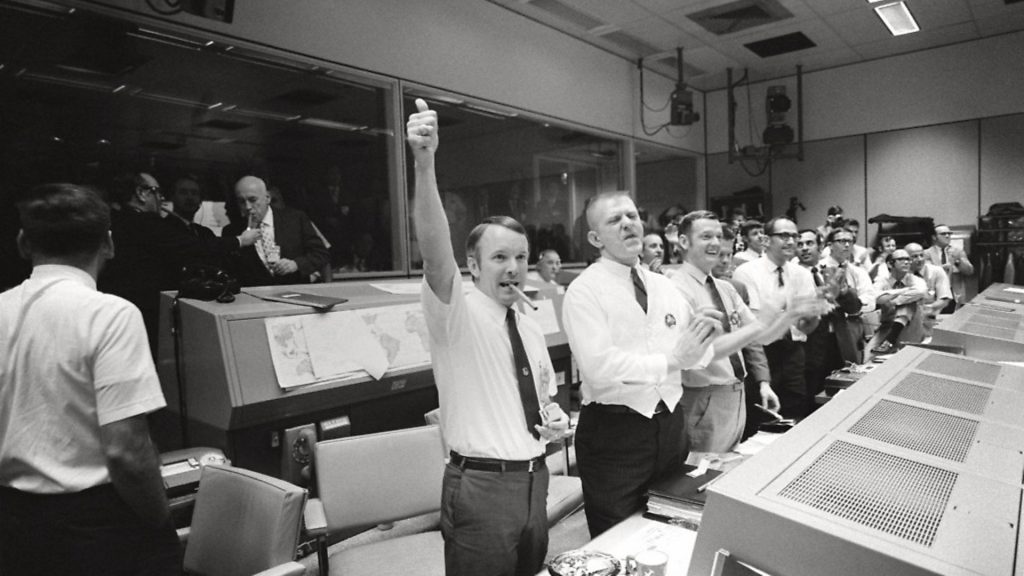

Within minutes the moon landing was cancelled, Apollo 13 was now all about getting the astronauts back to earth alive. ‘Failure is not an option’ was another phrase never uttered by those involved at the time (it was coined by the makers of the eponymous 1995 film, starring Tom Hanks as Lovell), but it perfectly summed up the attitude of the men and women at Mission Control back in Houston, Texas, headed by flight director Gene Kranz.

His co-flight directors and close colleagues Glynn Lunney, Gerry Griffin and Milt Windler were at work on rescue scenarios within an hour.

The story itself is now well known. A tale of rescue, of derring-do and technological brilliance that probably has no equal in the annals of humankind.

The Command Module was now pretty much useless; powerless and inert. Its engine could not be fired but the top section was still required for re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere so the Lunar Module (the lander that would have carried Lovell and Haise to the moon’s surface) was called into action as a lifeboat.

It would power the spacecraft to the moon (you can’t just turn round in space when you are heading one way at thousands of kilometres per hour), use the gravity of the moon to slingshot around the back and head home again.

But any number of other obstacles stood in the astronauts’ way. They all had to move into the Lunar Module where there was power, but only space for two. And although the Lunar Module had enough oxygen to get the men home, the carbon dioxide they were exhaling was contaminating their breathable atmosphere.

It would take four days to return to earth but only two days’ oxygen was available. There was a point shortly after the explosion when Mission Control concluded the astronauts were doomed.

Yet there was more hardship, including freezing temperatures as the astronauts strived to save battery power; having to use the Lunar Module’s crude descent engine to make vital course corrections (Like ‘flying with an elephant on your back,’ said Lovell afterwards); Haise picking up a urinary infection because the limited water had to be rationed (and used to cool the spacecraft’s systems) and condensation forming on the ice-cold instrument panels, meaning every flipped switch had the potential to short-circuit the spacecraft’s electrics.

Innovative minds back on earth adapted the damaged Command Module’s lithium hydroxide canisters, intended to absorb the exhaled carbon dioxide, so they would work in the Lunar Module, using copious amounts of duct tape and plastic sheeting to ensure a breathable air supply, while the astronauts rose to every problem and task thrown at them by the circumstances and their colleagues on earth.

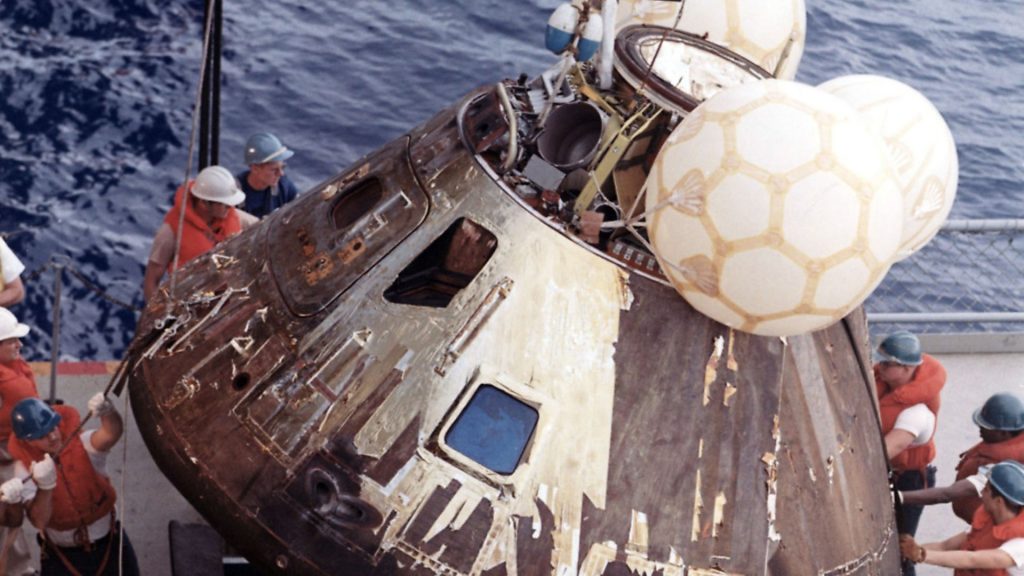

One final fear was that the heat shield on the Command Module had been damaged by the initial explosion and that the capsule and its occupants would burn up during re-entry. But on April 17, Apollo 13 splashed down in the Pacific four miles from the recovery ship USS Iwo Jima. Lovell, Swigert and Haise were alive.

The planet had watched transfixed. Suddenly space was cool again. After Sputnik, after Yuri Gagarin and after the Apollo 11 moon landing, it had all become a bit mundane, a bit ‘been there, done that’. TV viewing figures for the Apollo 12 moon landing the previous November had fallen through the floor. Now the world was watching again.

But while Apollo 13’s story is widely known, and immortalised in literature and film, what were its ramifications beyond the number-one priority of saving three lives? Was the impending but averted disaster politically damaging? Did it make politicians in Washington DC, terrified of the political consequences of Americans dying in space, more likely to pull the plug on the whole Apollo project? Or did the opposite happen? Did NASA, keen for publicity and even more keen for the Apollo missions to continue, manage to turn what could have been disaster for the space programme into a triumph – an almost Dunkirk-like reimagining of the whole narrative.

Shortly after the explosion Lovell was heard to say: ‘I’m afraid this is going to be the last lunar mission for a long time.’ The media quickly latched onto this – despite NASA administrator Thomas Paine immediately announcing that nothing had been cancelled – convinced that no American leader could risk humans in space again.

Yet, for whatever flaws he had elsewhere, president Richard Nixon had been generally supportive of the space programme. ‘The mission recaptured global attention on Apollo again but it led Nixon to consider the potential impact of a fatal space accident on his administration,’ says Teasel Muir-Harmony, curator of the Apollo spacecraft collection at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC and an expert in the politics of spaceflight.

‘He felt very connected to the crew, asked for updates twice an hour, and was known to treat astronauts as the sons he never had. But, that said, he was always concerned with re-election,’ she adds. ‘And he was always ambiguous about his position on Apollo and it’s often hard to determine exactly his relationship to the programme.’

This was obvious when Nixon made immediate political mileage out of the successful Apollo 13 return by flying to both Houston and then Hawaii, where the astronauts had been taken, to award them and the operations team the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

But Nixon also knew the American public had long had one eye on the fact that its tax dollars were funding adventures in space while back on earth more worldly issues such as the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement were more of a priority.

And their senators and congressmen and women were beginning to take note too. Apollo 13 just gave more emphasis to their attacks on NASA’s huge budget.

Yet Nixon himself was a pragmatist, before Apollo 13 he had already approved the funds for more moon landings and although after it he could see the risks, he was also aware of the political value of the programme and the reflected glory a president could bask in over its success. It was a balancing act, he didn’t want to be the one who canned Apollo, but also he didn’t want to risk the political destruction that could follow the loss of Americans in space.

With the 1972 election foremost in his mind Nixon repeatedly proposed that Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 be shifted until after it was over. ‘He thought another accident in space could ruin his bid, and these two missions would fall during the campaigning period,’ says Muir-Harmony.

And while Apollo 18 and 19 were both later cancelled for budgetary reasons NASA realised that Apollo 13 had thrown serious doubt on the viability of the moon-landing project.

The inquiry into the Apollo 13 explosion obviously meant that the next mission, Apollo 14 – due to depart in October 1970 – would be delayed (it eventually launched the following January). NASA was feeling the heat.

The Soviet Union, the United States’ big rival in space, took advantage of the hiatus by sending two uncrewed probes to the moon to collect soil samples, making great play of the fact that their missions had been achieved with no risk to human life (and cost far less). Media, both in the US and abroad, were increasingly disparaging about crewed spaceflight.

British weekly magazine New Scientist, a longstanding opponent, was especially dismissive, carrying a mere three paragraphs on the Apollo 13 mission over the course of three weeks and adopting a condescending ‘we told you so’ attitude.

It was then that NASA, realising that even if it and Apollo weren’t under direct threat it was now in the spotlight and looking over its shoulder as Congress eyed its budget. Another slip up and its existence would be hanging in the balance. It somehow had to turn the potential disaster of Apollo 13 into PR gold.

Capitalising on the enormous public attention the rescue had generated – 70 million Americans watched the astronauts’ return, millions more around the world, and nations across the planet offered assistance in whatever form, including the Soviet Union – NASA became aware of its great reach into the public consciousness.

As Jack Gould of the New York Times stated, Apollo 13 ‘which came so close to tragic disaster, in all probability united the world in mutual concern more fully than another successful landing on the moon would have’.

Thomas Paine constantly emphasised to the Nixon administration, often via his perceived ally the vice-president Spiro Agnew, that the Soviet Union would step into the metaphorical and literal void if Apollo was canned. And while this frustrated Nixon, who was dead set on a process of détente with the USSR both on earth and in space, it kept the issue at the forefront of political minds.

NASA took control of the narrative. The ingenuity that it had demonstrated in order to save Apollo 13 was repeatedly pushed out to the world – from a failure of technology had come technological brilliance. It mattered not that the official inquiry noted procedural discrepancies (although no individual was blamed for the faulty wiring in the tank) what was lauded was the selfless endeavour and collective genius that had been put into getting the astronauts home safely – American, home-grown genius.

Gerald Griffin, who would have been the flight director for the actual landing had the explosion not occurred, emphasised the teamwork that turned a desperate rescue mission into a commendable achievement through American sagacity. ‘You seldom heard the personal pronoun ‘I’ he said, ‘most of the time it was ‘we’, because we trusted each other.’

Likewise capsule communicator, or CapCom, Jack Lousma, the man who was the recipient of Swigert’s first message, stressed the professionalism of the team. ‘We just responded as we had to,’ he said.

‘It was a bunch of people who were trying to solve these problems as they came up.’ He would later say: ‘When Ron Howard made the [Apollo 13] movie and everybody found out what really happened, people saw that it was one of NASA’s finest hours.’

‘It’s something that should never have happened. Even though it gave us a great story, three lives were at stake,’ says Doug Millard, senior space curator at London’s Science Museum. ‘And it’s been variously described as a successful failure or a triumphant disaster. But on balance I’d argue that because NASA gave great emphasis to the way they improvised and their ingenuity, in the end it actually benefited the space programme.’

Nonetheless Nixon was intent on shifting spaceflight from being America’s top priority, to just one of many. And he was still preoccupied with re-election, increasingly concerned that Apollo 15 in July 1971 should be the last launch before his campaign got under way.

In May, according to John Logsdon’s book After Apollo? Richard Nixon and the American Space Program, he was insisting to his staff: ‘We have got to get off those damn moon-shots… none after July. I don’t want to risk any more.’

And after Apollo 15’s safe return there was no let-up, he wanted 16 and 17 to be postponed. ‘I don’t feel the shots are a big deal. There is the risk you could have another Apollo 13. There will not be any launches between now and the election.’

But Nixon did not get his wish. Apollo 16 went on schedule in April 1972. NASA had spun the Apollo 13 narrative, outmanoeuvring the president who would soon be enmeshed in a scandal that would demand far more of his time than the space programme.

On the one hand you had a public who wanted its tax dollars spent on earthbound issues, a pragmatic orthodoxy that appealed to the political base, yet on the other hand perhaps the greatest single instrument of American soft power – a foreign policy by proxy – was its space programme and specifically Apollo.

Walking on the moon was a feat that people everywhere could admire. Apollo 13 fitted perfectly into that narrative – American resourcefulness saving three of its chosen sons.

And NASA was being canny too, offering the government a concession. ‘After Apollo 13 they decided to cancel two Apollo missions, numbers 15 and 19,’ says Muir-Harmony. ‘Apollo 20 had already been assigned to Skylab (America’s first space station) so that meant three missions would no longer fly.’

To avoid numerical confusion Apollo 16 became Apollo 15 and so on. For a while Nixon and the politicians in Washington were mollified, but as election year approached he became twitchy about Apollo 16 and 17 again.

‘In some ways it can be considered good luck the accident happened when it did,’ says Muir-Harmony. Interest in the programme was waning and a presidential election was looming. ‘In the end a kind of compromise was reached.’ Nixon was aware that Apollo 13 had sparked renewed interest so he didn’t want to be responsible for being the man who cut the purse strings, instead just reining it in until he could be re-elected. ‘NASA convinced the public and Nixon of Apollo’s benefits,’ says Muir-Harmony, ‘and Nixon realised he could downgrade the programme in America’s list of domestic priorities.’

In the end Nixon cut the budget but kept the programme, including Apollos 16 and 17 (although the latter would launch after election day). This was more Nixon pragmatics at play. ‘He also realised the importance of the aerospace industry to California’s economy,’ points out Muir-Harmony, ‘and he hoped to win California in the election.’ Nixon, of course, did get re-elected although after being consumed by the Watergate scandal the following year he might have wished he hadn’t.

There was a lot of luck surrounding the flight of Apollo 13, its designated number notwithstanding. It was fortunate the explosion happened on the outward flight – had it happened while the lunar module was on the moon there would have been no Command Module to return to in orbit. Had it happened on the return journey there would have been no Lunar Module to carry the astronauts back home. And there was double-edged luck too for Jack Swigert. Three days before launch he hadn’t been on the flight. The original Command Module pilot Ken Mattingly had been exposed to German measles and was not immune. Had it not been for NASA’s ingenuity Swigert would have been on the receiving end of the worst luck of all. And Mattingly never did come down with rubella.

In 2015 Jim Lovell lauded the political reconfiguring that NASA had performed – the proverbial disaster turned into triumph. ‘The flight was a failure in its initial mission,’ he said. ‘However, it was a tremendous success in the ability of people to get together, like the mission control team working with what they had and working with the flight crew to turn what was almost a certain catastrophe into a successful recovery.’ Stealing a quote from Winston Churchill, Apollo 13 has since become known as ‘NASA’s finest hour’.

Fifty years ago, to use another outworn cliché, the world held its breath. ‘The astronauts’ survival was in doubt throughout the mission,’ says Muir-Harmony. ‘Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman, a confidante of Nixon’s, told him to be ready for the worst outcome.’ That the astronauts returned is not only one of the great adventure stories in human history, it was also the triumph of tenacity over adversity and, as we have learnt, of bravado over politics.