Alan McGee was the 1990s record label boss who got an invite to Downing Street at the height of Cool Britannia. He talks to MATT WITHERS about that era, the future of rock ‘n’ roll, politics and his loathing of BBC 6Music… and London.

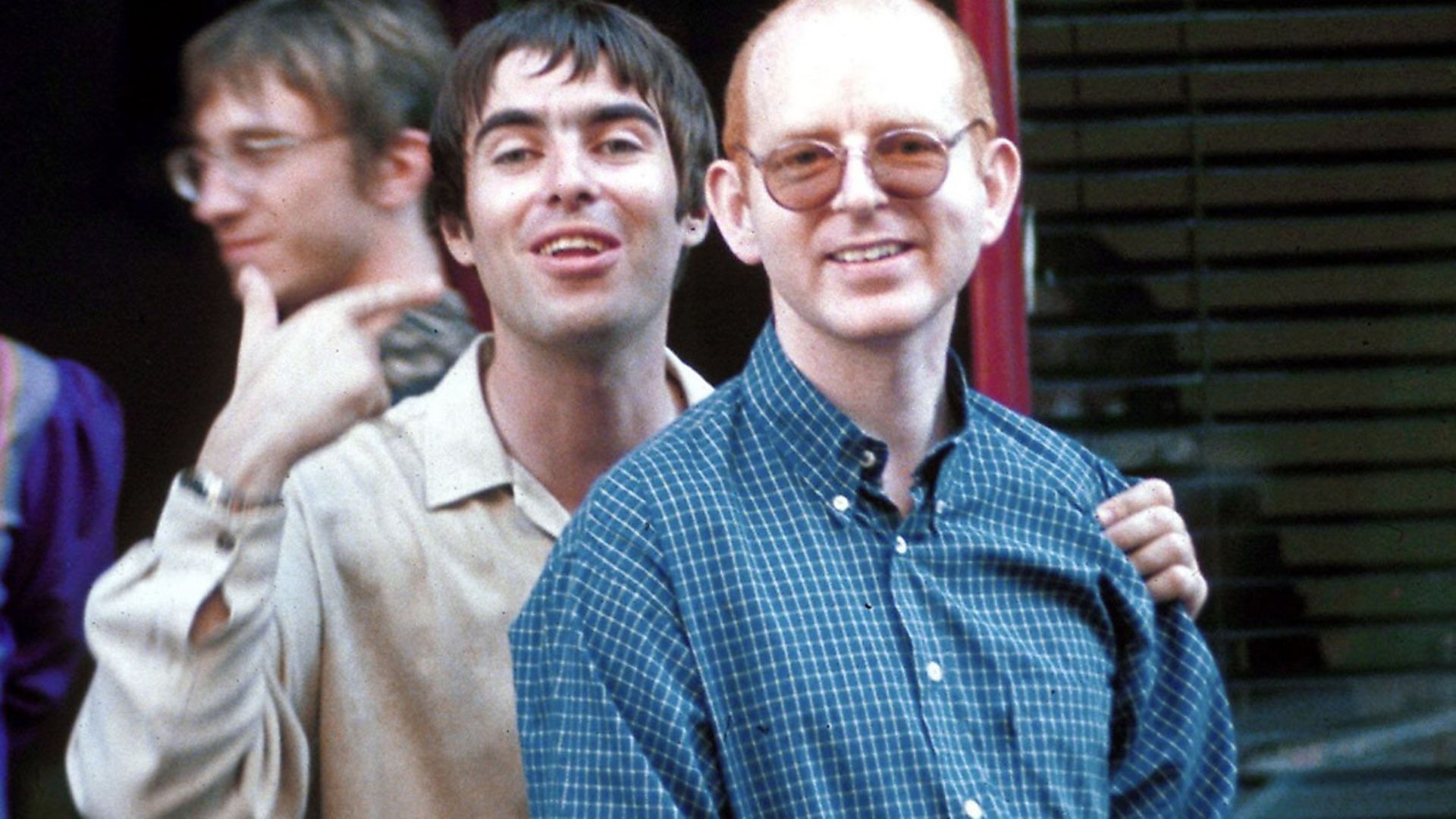

Speaking to Alan McGee – music manager, Creation Records founder and the man who famously signed Oasis – I remind him of an interview he gave a decade ago, in which he said he’d lost interest in music. So what album or which act, I wonder, had rekindled the love affair for him?

‘I was off my nut on prescription drugs,’ he says more prosaically of that time. ‘So probably that particular few months I believed it.’

McGee spent lockdown at home in London, from where he speaks to me. Having spent last year at more than 100 gigs, either his own one-man shows or watching the bands he now manages, like the Happy Mondays, Cast and Glasvegas, he ‘actually enjoyed it, to be absolutely honest’, he says, as have a lot of friends. He laughs at the thought of Shaun Ryder and Will Sergeant, of Echo & the Bunnymen, relishing pottering around the house.

We speak ostensibly off the back of the second anniversary of launching Creation 23. The original, hugely influential label was wound down in 1999 amid the Glaswegian’s disillusionment. The successor was created simply to put records out again, he says.

‘I’m not really part of the industry,’ he says. ‘We’re not a corporate management company. It’s me and two people that I work with on the management and with the label it’s literally me and my iPhone, mate.

‘You know what? I don’t think the music industry want anything to do with me, which is actually alright. ‘Cause, believe it or not, sometimes when people just ignore you, actually you can do good work. So I’m not particularly troubled by that.’

I wonder if the ‘old’ Creation could ever happen again in a much-changed world of streaming. ‘Yes and no,’ he says. ‘I mean, this is pretty punk what I’m doing now. It’s a guy and an iPhone putting out records by people with no contracts and 50/50 deals. It’s kind of punk as you want it to be, you know what I mean?’.

He agrees that, compared with Creation’s period of enormous success in the 1990s, it’s a labour of love. But he adds, ‘it’s always been like that’.

‘Sometimes I’ve been really, really popular with the bands, the bands have really connected,’ he says. But it’s tough when, he claims, the BBC’s influential 6Music isn’t interested in the sort of music – guitar music, basically – he’s putting out.

‘I think things like 6Music – I think they’re the problem more than anything else, ’cause it’s so middle-class,’ he says.

‘And it’s so f***ing thought-through and so politically correct, it’s so f***ing boring, man. And I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’m not anti anybody, I’m just saying that… 6Music – that whole thing, it’s so Guardian, it’s so 1975 except it’s 2020. I think they’re the problem.

‘They actually said to the plugger ‘Alan’s releasing the sort of music that we’re not interested in’, and it’s a bit like, well, it’s interesting that you say that, because most of the time you play all of my old records from the f***ing ’90s, like Primal Scream and the Valentines and Oasis – your f***ing station emerged out of the records that I put out.’

We talk about a conversation I had with a friend recently in which we attempted to pin-point when young people stopped picking up guitars and forming bands. A disclaimer: I’m 40, and so are most people I know, but a quick glance at the singles charts would not appear to show the genre in rude health. McGee disagrees and suggests I need to get out of London.

‘There’s a scene that no doubt will blow up eventually,’ he says.

‘Young northern white kids that like rock ‘n’ roll. It might not be trendy in London… but that audience is getting bigger from what I can see. It’s just expanded into a whole kind of like, you know, ‘if you play any music like that it’s uncool’. When I signed Oasis a guy who ended up making his career off of me signing Oasis looked at me and said ‘Alan’. I said ‘this is the future of rock ‘n’ roll’. I’m not taking the p***, Matt, on my kid’s life, I actually said that. And he went, ‘Alan, Madchester’s over’.

‘So we’ve been here before. It always doesn’t exist in the media’s eyes, mate.’

Still, I venture, it’s unlikely a rock band from, say, Newcastle, will win the Mercury Music Prize any time soon.

‘Let me twist it,’ he responds. ‘Why would you want to win it? Who cares? These people are irrelevant. The f***ing Mercury Music Prize – nobody f***ing cares what these c***s think.’

Another thing is the culture of guitar music. Is it just the lack of new, mainstream bands that means rock hasn’t had its #MeToo moment yet? After all, tabloid tales of groupies and excess were as much a part of rock as the bass and drums.

‘That was never Creation, man,’ he insists. ‘That was never us. I think the Me Too movement is good because I know, like we all do, insane stories about a lot of these f***ing people. We were lucky – I come from punk. We had bands like the Slits. So we were aware of feminism when we were young men. So that was never us.

‘The generation that came before us – the glam generation – that was them. But the Gallaghers – if you’re talking about that culture that we supposedly represent – were pretty feminist, ultimately. They always had women in charge of their business. So it wasn’t jobs for the boys. You can’t really level that at us. Again, that’s the middle class London media.’

For me and my generation, the period McGee, Creation and Britpop embodies still seems an exciting period to be a teenager. But I do wonder if the tail-end of Generation X romanticises the 1990s. The Tories were in charge of 70% of it, after all, and Britpop also gave us Menswear and Northern Uproar.

‘It was a great time, do you know what I mean?,’ McGee happily confirms. ‘It was a f***ing great time.

‘I mean, I loved that time because everything became possible. We were young, some of it we got wrong. I thought it was going to go on forever, the ’90s. But you know, I’ve just kept going. I’ve had five years out to bring up my daughter, 2008 to 2013, wrote a book.’

That book, Creation Stories, is about to become a film, co-written by Irvine Welsh, executive produced by Danny Boyle and starring Ewen Bremner as McGee.

‘It’s really funny,’ McGee says. ‘Whether it’s really me… I don’t know, mate. It’s like it is me and it isn’t me. It’s taken a lot of stories from my book, but I haven’t been a particularly dramatic character for 25 years. I mean, 25 years ago I was f***ing mad. I accept that.

‘But I haven’t been particularly dramatic for a long time, so I’m watching this mad guy on screen who was on a mission to change things, and I think we kind of did to a certain extent. I can live with it, which is maybe the biggest compliment I can pay the film.’

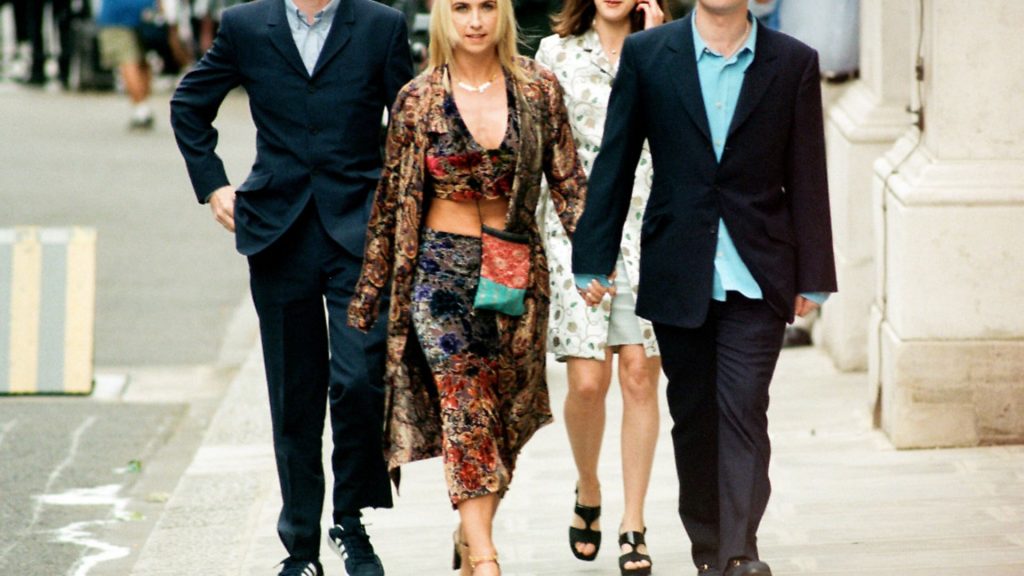

Both Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson are portrayed in the film (the former by an actor who has twice portrayed Hitler), which is a reminder that music and politics are entwined in the Alan McGee and Creation story. McGee donated around £100,000 to Labour, was entertained by Blair at Downing Street receptions and was largely responsible for changing legislation to allow musicians to go on the ‘New Deal’, giving them three years to develop and receive funding (it was scrapped in 2009). McGee would later break with the party, citing ‘control freakery’. Where is his political home now, I ask?

‘I quite liked Blair, but then he went and done the Iraq thing, which was a f***ing mistake,’ he says.

‘But I couldn’t get into Corbyn. For me it was like… I just thought he was unelectable. I mean, everybody else saw him as this wise old guy, I just saw him as the cranky geography teacher. It just was so London. Working-class people, in Glasgow and f***ing Newcastle and blah-blah-blah, they looked at Corbyn and they were nae buying it. Labour won that election for f***ing Boris.’ Keir Starmer has yet to inspire: ‘I’ve got to be honest, not really.’

McGee still gets criticism for being the punk who went behind the black door of Number 10 to be glad-handed by the New Labour government, but is unapologetic.

‘I only went into 10 Downing Street, mate, because I wanted to see it. It’s not that complex. I went, and then when I got the chance to change the law for all the musicians, I f***ing changed the law. People who slag me off for that – it is what it is. We took s**t for it, but I don’t regret it.

‘I still see Tony Blair occasionally. I went round to his office a couple of years ago. And you know what? He’s brilliant, but the Iraq thing was so f***ing wrong. And you can’t really get past that, Tony, you shouldn’t have done it, mate.’

McGee was firmly anti-Brexit, but says that ‘in the wake of Covid I don’t think anybody’s even f***ing thinking of the no-deal Brexit that probably going to hit us between the eyes in four months’ time’.

And what of Scottish independence? McGee says that, now having lived longer in England than he did back home, ‘it’s not really my fight, but I think they should have their independence. And I support them. But I’m never going back.’ He considers himself a Londoner, he says, cheerfully admitting to being a hypocrite having spent much of the interview railing against the capital.

And he has his own historic date coming up anyway, as one of the hard-livers of a particularly hard-living decade enters his seventh decade – with relish.

‘I’m 60 in two months and I always thought I was going to have a problem being 60, but I’ve actually embraced it, I’m actually alright about it,’ he says.

‘I’m into it, I’m totally into being what I am, 60. ‘Cause I’m still doing it and I’m still being truthful and honest about what I do, do you know what I mean? Which is f***ing music.’