When American rock met European art – a bizarre chapter in rock history to which countless other acts, from David Bowie onwards, owe a debt of gratitude.

As a solo act Alice Cooper is known as a golf-playing born-again Christian, a preacher’s son who played the part of a chicken-killing, snake-wielding vaudevillian ‘shock rocker’.

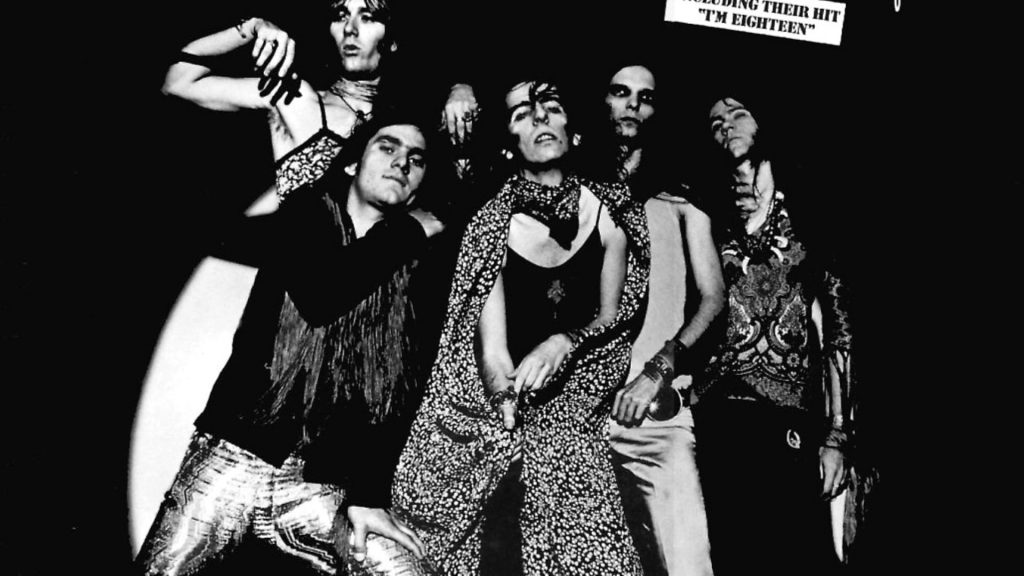

But Vincent Furnier only became ‘Alice Cooper’ by degrees, and his solo career has overshadowed the influential work of the band, which the name originally referred to. As Alice Cooper, Furnier, bass player Dennis Dunaway, drummer Neal Smith and guitarists Michael Bruce and Glen Buxton, made a decisive break with the peace and love rhetoric of the hippies, and their flamboyance, legendary stage show and theatrical exploration of the dark themes of madness and murder were formative for glam rock, punk and heavy metal.

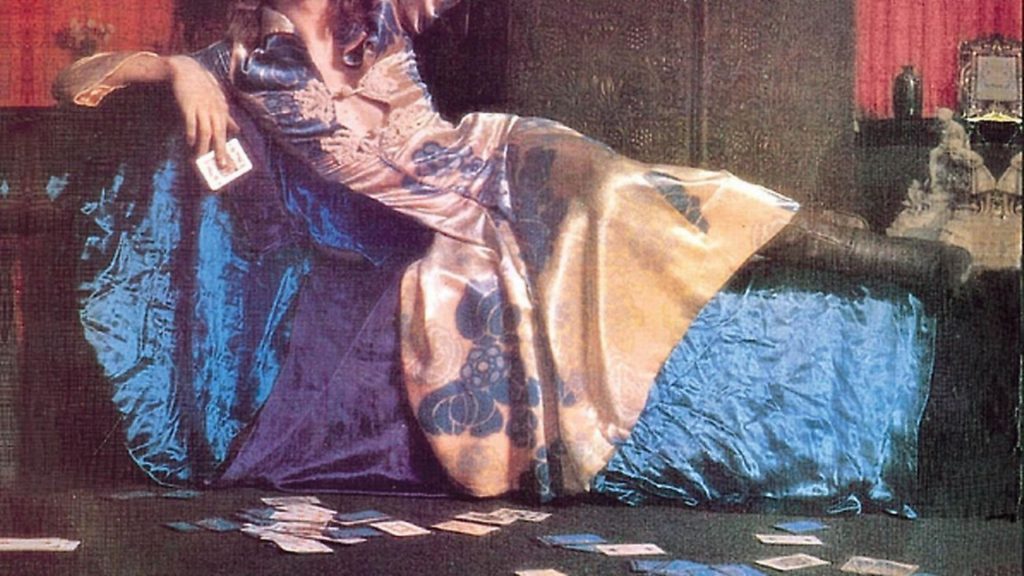

The cultural cachet of the band in their heyday is indicated by a strange episode which brought together American rock and European art – the creation of Salvador Dalí’s 1973 artwork First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain. The piece brought together two artists whose best work would come to be obscured by their pursuit of the outrageous and the sensational, but was emblematic of a time when the marriage of art and rock was being widely explored.

At a suitably chaotic Manhattan press conference in April 1973, Dalí explained the artwork he was about to create to the assembled press, as a bemused Alice looked on. Dalí, in a white and gold chasuble, looked like a holy man and contrasted wildly with Alice’s decidedly insalubrious appearance, in leather and smeared black eye make-up, accessorised with the ubiquitous can of Budweiser.

Dalí proclaimed himself and Alice the ‘greatest living artists’ (the death of Picasso four days later decisively ended a five decade rivalry over who could claim this title), and he called Alice ‘the best exponent of total confusion I know’, before producing an ant-covered plaster brain topped with a chocolate éclair, calling it ‘the Alice brain’.

The brain was placed on a red velvet cushion behind Alice’s head as he sat on a rotating turntable wearing over a million dollars-worth of diamonds from the famous Harry Winston jewellers on Fifth Avenue, holding a fragmented Venus de Milo as a microphone. He was photographed in this pose in 360 degrees to create the hologram.

At this time the 68-year-old Dalí was a superstar whose embrace of the commercial and the popular had driven his fame. Having established himself internationally in the 1920s and become part of the circle of Surrealists in Paris, he was expelled from the group not only on the grounds of his refusal to denounce the rise of fascism in Europe, but also because of his ‘vulgar’ commercial awareness. He would go on to do window displays for New York department stores, edit a special edition of French Vogue, design the Chupa Chups logo and appear in several television adverts for the likes of Alka Seltzer and Datsun.

Dalí knew how to promote himself and others and the Alice escapade was far from his first brush with the emerging icons of pop music either. His muse, French model, Gold-selling pop star in France and Germany and later Italian television host Amanda Lear, was his direct link to figures such as Brian Jones, Bryan Ferry and David Bowie, all her sometime lovers. She would appear on the cover of Roxy Music’s For Your Pleasure and on Bowie’s television special, The 1980 Floor Show, from the year of the hologram portrait. Dalí was plugged into a creative world far beyond the artist’s studio.

Alice Cooper’s stock was also high in 1973. As purveyors of an undistinguished psychedelic garage rock, they were signed by Frank Zappa, who was meant to produce their debut Pretties For You, but with characteristic ‘experimentation’ put out recordings of their rehearsals instead. January 1971’s Love It to Death was the band’s breakthrough, marking the beginning of a fruitful relationship with producer Bob Ezrin, who would go on to work with KISS, Pink Floyd, Deep Purple, Peter Gabriel and Lou Reed. The album contained all the elements of their new style – proto-heavy metal (Black Juju), theatrical narrative numbers (Ballad of Dwight Fry), camped up covers (Sun Arise) and soaring guitar rock (I’m Eighteen). Their third album School’s Out had gone top 10 across Europe and the US (the eponymous single would be the band’s only number 1, topping the charts in the UK in August 1972), and they had just seen the follow-up Billion Dollar Babies go to number 1 in the UK, US and Netherlands. Working with Dalí fitted the band’s attention-grabbing agenda perfectly. Alice’s camp, rapier-waving performance of School’s Out on Top of the Pops had already drawn the opprobrium of Mary Whitehouse and all its attendant media attention, and a truck carrying a billboard image of Alice wearing only a snake, advertising a forthcoming show at Wembley, mysteriously ‘broke down’ on Oxford Circus the same summer, causing chaos. Yet, for Dalí, the Cooper hologram was more than just a publicity stunt and it related to themes he had been pursuing for two decades.

Throughout the 1970s Dalí worked with optical illusions and stereoscopic images, the subject of a current exhibition at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres, Spain, but his interest in working in the third and fourth dimensions dated back further. His 1958 Anti-Matter Manifesto proclaimed his intent to abandon his exploration of the interior world for a focus on ‘the exterior world and that of physics [which] has transcended the one of psychology’, saying he had swapped Freud for Heisenberg. The tesseract cross of his Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954) was inspired by the diverse influences of mathematical theory, cubism, and works of Philip II’s architect Juan de Herrera and Catalan mystic Ramon Llull. The Alice hologram may have taken an emerging popular icon as its subject, but the medium was one which fulfilled Dalí’s artistic ambitions at the end of his career to embrace science and break out of the two dimensional.

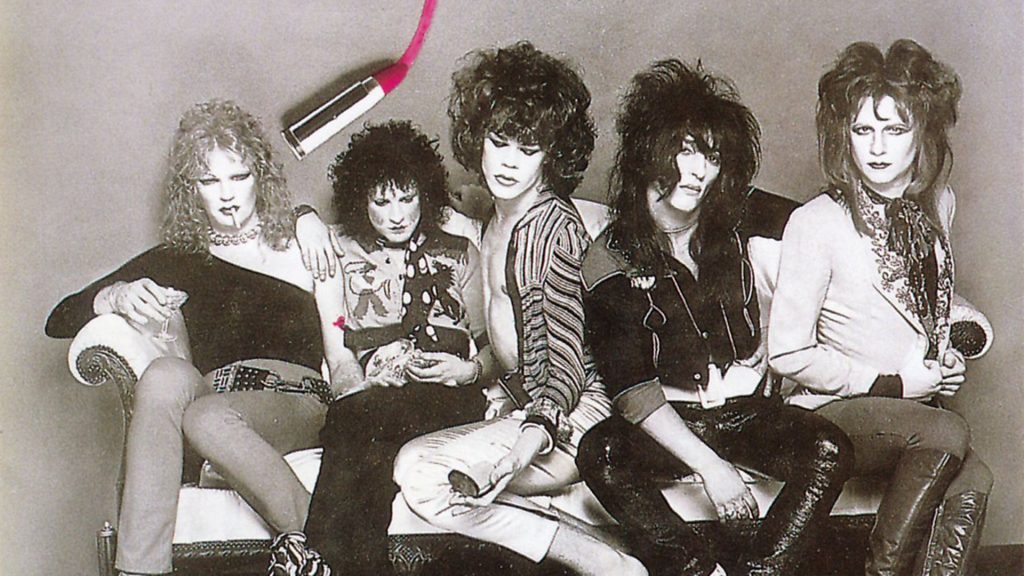

For their part, Alice Cooper – after all, a bunch of former art students – felt their artistic vision had reached its apotheosis with the Dalí piece, and they were forging something truly new, influencing generations of future music stars in the process. The cover of Love It to Death showed blonde, statuesque drummer Neal Smith pouting in a skimpy lace top, while a kohl-wearing Alice was draped in a floral scarf that looked like a dress. This pipped Bowie in a ‘man’s dress’ on the cover of the UK release of The Man Who Sold the World to the post by three months and well anticipated the New York Dolls in high drag on the sleeve of their debut of 1973. Elton John and David Bowie reportedly saw Alice Cooper live during their first tour of Europe in 1971.

The costuming and fully worked-up stage show, complete with the execution of Alice by electric chair at the climax, was an ‘oasis in the desert of dreary blue-jeaned aloofness served up in concert by most American rock-and-rollers’, according to Rolling Stone’s John Mendelsohn’s contemporary review, and many soon-to-be glam rockers picked it up and ran with it. When John Lydon auditioned for the Sex Pistols in 1975 he sang, or at least mimed to, I’m Eighteen, and the direct line between Alice Cooper and every possible genre of metal is obvious. The Dalí work brought the band well and truly into the orbit of art and occurred at the high point of their career, but a decline soon followed.

In his brilliantly-titled memoir, Snakes! Guillotines! Electric Chairs!, Dennis Dunaway recalls that Alice went to the grand unveiling of the finished Dalí hologram alone, leaving the band uninvited, and it was the shape of things to come. With the band ostensibly still together, Alice released Welcome to My Nightmare in 1975, using Lou Reed’s backing band from the Ezrin-produced Berlin instead of his regular bandmates. Promoted with an ABC television special starring Vincent Price and an epic 103 date tour with lavish theatrics, including tightly choreographed dancing skeletons and Cooper being chased around the stage by a huge furry cyclops, the album’s lead single Only Women Bleed was a hit in the US and Canada. The band would not play together again, and for Furnier alcoholism and cocaine addiction followed, but his 1989 hit single Poison would crown his recovery, and the stage formula worked out for Welcome to My Nightmare has continued to fill arena venues across the world.

Now pushing 70, Vincent Furnier is back as Alice once again, releasing Paranormal next month. Produced by Ezrin, the album includes two tracks featuring his first work with his surviving former bandmates in over four decades. In November they will play the UK together for first time in 46 years over a five date arena tour. Whether they will be able to recapture the chaotic theatricality of the original band remains to be seen, but they changed the face of rock music in the 1970s, and artists without number today owe them a debt for showing how art and music could be fused.

Dr Sophia L Deboick is a freelance writer and historian specialising in popular culture