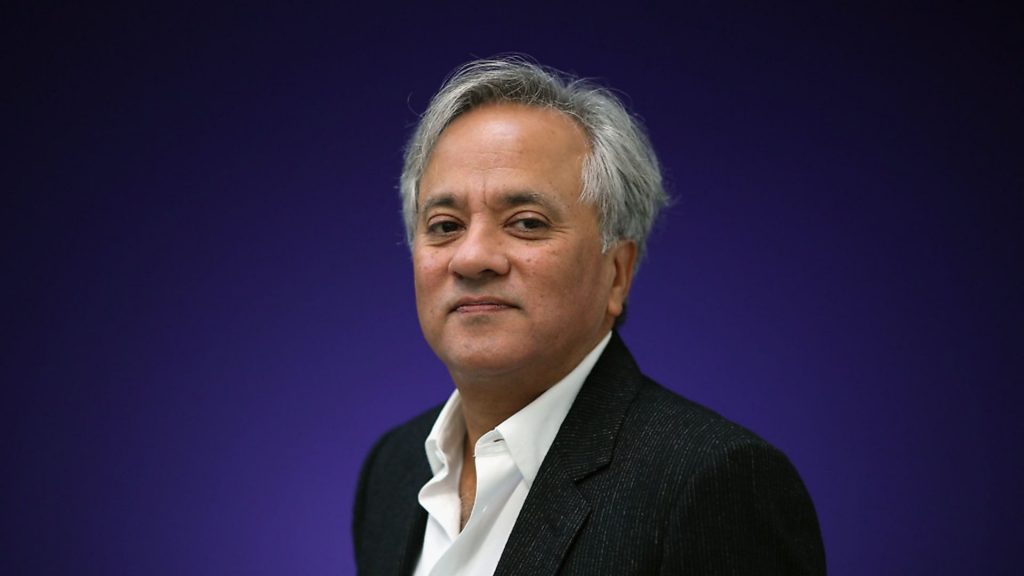

With superstar sculptor Anish Kapoor’s work, setting is everything – as FLORENCE HALLETT finds when she visits an island exhibition on a Norwegian fjord.

On the little island of Jeløy, the vast Oslo fjord is never far from view, lush countryside and neatly tended fields a picture of bucolic harmony against a backdrop of water that sparkles in the sun.

If the occasional timber farmhouse makes this a typically Scandinavian scene, the avenue of trees on the approach to Alby manor house, home to Gallery F 15, one of Norway’s leading contemporary art galleries since 1967, transports us directly to France.

A simple but pleasing example of 19th century neoclassical restraint, the house itself also looks to more southerly climes for its inspiration, and its landscaped gardens recall those of England’s country houses. Anish Kapoor’s Sky Mirror, 2018, really ought to be an odd intrusion here, its polished stainless steel surface a jarring anachronism in a setting defined by the gentle shapes of nature and infused with a sense of its past.

Instead, the mirror is absorbed into the landscape, exaggerating the effects achieved by the designers who laid out the grounds almost 200 years ago. The manor was bought by the politician Jonas Anton Hielm in 1824, and he transformed the garden into an escapist fantasy, with fish ponds and a rabbit island, a drawbridge and a cave providing a setting for garden parties that were punctuated by gun salutes and fireworks.

The lawn drops off sharply, hiding the fields beyond to create an illusion of the water coming up to meet the house, producing the sort of enveloping calm required of a summer retreat. Earth meets water, which in turn merges with the open sky, an effect concentrated and intensified in the mirror’s dishlike surface.

In drawing so readily on its setting, Sky Mirror sets the tone of Gallery F 15’s exhibition dedicated to the Indian-born British sculptor Anish Kapoor, who first came to public attention in 1990 when he represented Britain at the Venice Biennale.

A year later he won the Turner Prize, and in 2009 he was the first living artist to be honoured with a solo exhibition at the Royal Academy in London. Best known for public commissions such as the ArcelorMittal Orbit, popularly known as the helter-skelter, which was made for the Olympic Park in 2012, today Kapoor is one of the most celebrated artists of his generation, this small show in Norway is one of four European shows over the summer.

Jointly curated by Dag Aak Sveinar, director of Punkt Ø, the umbrella organisation that runs Gallery F 15, and Alnoor Mitha, senior research fellow at Manchester School of Art, Gallery F 15’s show is not a retrospective, but spans Kapoor’s career even so, bringing together nine works, including sculptures, drawings and etchings, that mark some of the most memorable points in the 40 years since he graduated from Chelsea College of Art in 1978.

If hosting a show by Kapoor emphasises Gallery F 15’s aspirations as a home for international art, the island of Jeløy already has a notable artistic heritage, and next year the gallery will host the 10th edition of Momentum, one of Scandinavia’s most prestigious art biennials.

Gallery F 15 has also staged an exhibition on Edvard Munch, who, famous for his painting The Scream, 1893-1910, lived on Jeløy, at the nearby Grimsrød farm between 1913 and 1916.

Here he lived simply, keeping a number of animals and picking wild berries. But far from providing a life of austere rural isolation, Jeløy seems to have been perfectly accessible, and Munch received regular visits from foreign collectors and gallerists, as well as clients wishing to sit for their portraits.

While Jeløy provided a suitably contemplative working environment for Munch and subsequently for the display of Kapoor’s sculptures, the island’s location on the Oslo fjord and its proximity to Moss, a town with a long history of shipbuilding and industry, place it on one of the most important shipping routes in northern Europe.

Both place and passage mean something to Kapoor, and he explains that ‘the idea of place has always been very important to my work. A lot of my works are about passage, about a passing through, and that necessitates a place’.

In fact, many of Kapoor’s sculptures can be understood as places, or passages, in their own right, and in drawing us into a micro-world of altered perceptions and challenges to the senses, he invites us to examine our reactions afresh, both considered and instinctive.

An apparently simple idea, such as the notion of a surface becomes problematic in Kapoor’s work, with depth and mass suggested through pigments and mirrors. Surfaces that alternate between the highly reflective and entirely light-absorbing, serve as gateways to novel and often unsettling spatial experiences, and in their ability to delight and enthral they offer an equivalent to Hielm’s 19th century follies.

When I am Pregnant, 1992, plays most openly to the sensibilities of a folly, the curious bump in the wall appearing and receding as we move around the room, with curiosity about how it got there, and the way in which it was made, occupying visitors every bit as fully as its interpretation.

The domestic scale of Alby provides a disconcerting setting for Void, 1994, a fibreglass shell covered in a pigment so matt that it reflects no light at all, suggesting an endless emptiness that could so easily be fallen into.

The many tiny mirrors that make up Hexagonal Mirror, 2007, distort and multiply the viewer’s reflection, amplifying voices, and taking us to what feels like the edge of a precipice, from where we can contemplate a vertigo-inducing plummet into a confusing and apparently infinite space.

From the dead black of Void, to the minutely controlled distortions of Hexagon Mirror, Kapoor’s work often hints at an engagement with scientific ideas, an interest that allows a satisfying symmetry with the history of the house.

Jonas Anton Hielm, the enterprising politician who transformed the gardens in the 19th century, set about establishing a botanical garden which he supplied with exotic plants brought to Norway by ships returning from voyages all over the world. A beautiful acacia tree still survives, its trunk twisted with age, and propped up to prevent its total collapse.

The role of trade in broadening horizons and facilitating cultural exchange seems implicit in Kapoor’s work, and the sensual appeal of the marketplace is evoked in the earliest piece on show, White Sand, Red Millet, Many Flowers, from 1982.

Shapes cast in concrete and then covered with powdered pigment in black, red and yellow are almost irresistibly tactile, and director Dag Aak Sveinar points out that preventing visitors from touching the works requires constant vigilance from the gallery’s staff.

Clinging to each object like icing sugar on a cake, the powdered colour collects around the base of each form to suggest the decorative piles of spices and pigments found in Indian markets, conjuring a world of rich perfumes and textures, where sound, smell and touch are as compelling as any visual impact.

If the setting seems to push matters of trade and international relations to the forefront of this exhibition, Kapoor himself acknowledges the importance of commercial and political ties in fostering a healthy cultural scene, adding: ‘One has to have a relatively sophisticated attitude to money, it costs money to make things and that’s the way of the world.’

Asked if he felt that Norway might offer a model for Britain’s new relationship with Europe, he declined to answer, saying he knew too little about it, and indeed it is not at all easy to find a Norwegian willing to recommend the ‘Norwegian model’, despite the enthusiasm with which it is proposed by some British politicians.

What is clear is that organising an exhibition such as this one requires close co-operation between the two countries, with loans from the Arts Council England and the British Council appearing alongside pieces from the Anish Kapoor Studio, loans from private collectors in Norway, and the Lisson Gallery in London.

Like so many British artists, Kapoor is a committed Remainer who has been outspoken in his dismay over Brexit. In an interview with the Guardian in 2016, he warned of the likely negative impact of Brexit on audience figures for art and the continued availability of funding streams, but today his concerns are focused on its emotional and philosophical impact.

Asked to comment on the effect of Brexit on artists and the art world, he said: ‘It’s the most depressing moment in our troubled recent history. Art reflects our national consciousness, but now we’ve just dug a big hole and buried it for ever.

‘Great Britain is a great country, a place of tolerance and open-mindedness. But today it looks narrow-minded, small-hearted and mean-spirited. Art is being part of a global conversation. Now we are going to think small.’

SEVEN WONDERS OF KAPOOR

ArcelorMittal Orbit

Designed for the London Olympics in 2012 and built in the park which hosted the games. The observation tower stands 376ft tall and is Britain’s largest piece of public art. It is made of 35,000 bolts and enough steel to make 265 double-decker buses.

Building for a Void

Commissioned in the early 1990s for the Seville Expo, the concrete stucco tower, developed in collaboration with designer David Connor, was said to be generated around a void in the ground. Inside, the half-egg-shaped interior of polished plaster was bare except for an oculus in the ceiling. The structure was later demolished, when the site was redeveloped for a theme park.

Dismemberment Site 1

A huge, red, trumpet-like structure, built into the undulating meadows of northern Auckland. It is 82ft tall and 279ft in length and comprises a vast PVC membrane stretched between two giant steel ellipses.

Cloud Gate

The centrepiece of a public park in the Loop area of downtown Chicago, it is nicknamed ‘The Bean’ by locals, due to its shape. The structure is made up of 168 stainless steel plates, welded together, yet there are no visible seams on its highly-polished exterior. It was inspired by liquid mercury and its surface provides distorted reflections of the surrounding city skyline.

Ark Nova

An inflatable, orb-like mobile concert hall built to tour areas of Japan which had been hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. The walls of the structure – which seats 500 – are made from a stretchy plastic membrane, designed to enable quick construction and dismantling.

Turning the World Upside Down

The hourglass-shaped sculpture is placed at the Israel Museum, in Jerusalem. Made of polished, stainless steel it projects an inverted reflection of the world, with the ground high above and the sky below.

Dirty Corner

Installed at Versailles, the sculpture has been the source of much controversy. It has been dubbed ‘The Queen’s Vagina’ and vandalised several times. The huge, steel tunnel is almost 200ft in length and 30ft high. Visitors are invited to enter, deeper into the void of darkness, up to a point that the light at the other end is no longer visible and they are forced to use their senses for judging the way forward.

Florence Hallett is a freelance writer on art and visual arts editor at theartsdesk.com

Anish Kapoor runs at Gallery F 15, Jeløy, near Moss, Norway, until October 14; visit momentum.no/exhibitions.181198.en.html