Just how much blame for the disasters of the last two centuries can be placed at the feet of this overbearing gang?

When it comes to apportioning blame for the catastrophes that befell Europe in the first half of the last century, it is ‘the Germans’ who usually take the lion’s share.

History is, of course, rather more nuanced than is allowed by such a rigid approach. Not only does it overlook the great contributions made by the country and its people in so many fields, from the arts to literature and philosophy, but it also has the effect of letting other countries off the hook. A massive part of the history of Europe is the history of war-mongers, nationalists, revolutionaries and imperialists of many stripes – who were prepared to kill and destroy anything that got in their way.

There is, perhaps, one group, however, which does deserve its own chapter in that history of war-mongering, nationalism and imperialism. A group which, in many ways, ‘hijacked’ Germany, blunting the country’s great qualities and doing much to send it on its path towards destruction and tragedy: the Prussian Juncker class.

Of the many Germany states that were unified into a single country in the 19th century, Prussia was the most important and most powerful. Yet the original region of ‘Prussia’ was not remotely in what we really consider to be ‘Germany’. In fact it was on the Baltic shore roughly where Poland now meets Lithuania. It was here, in the 13th century, that a group of Teutonic Knights came, saw, conquered and stayed.

Three centuries later, the territory came under the control of the Hohenzollerns, whose power base was the Margraviate of Brandenburg, centred on Berlin. This Margraviate had two things going for it: it was at the centre of Europe – and thus of strategic importance – and it had a number of navigable rivers and lakes running across its broad plain, which were of great logistical benefit.

However, the region was also a place of poor farmland with thin and sandy soil. Prussia, by contrast, was rich and fertile. So the powerful families of Brandenburg sent their young sons (Junkers, or ‘young lords’) to the wild Prussian east to make their fortunes and build estates there. The fact that this political entity – comprising the lands around Berlin and the contrasting area much further east along the Baltic – became known as the Kingdom of Prussia signifies just how important the eastern region was in the Prussian (and later, German) imagination.

The Hohenzollerns also governed a series of other principalities, many of which were not physically connected, that ran from the Rhine across the north European plain to Prussia. Much of the brutal 30 Years War (1618-1648) took place across these regions and, at times, it looked as if the Hohenzollern/Prussian interests would be destroyed.

However, a series of talented kings and leaders throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries built Prussia up to be one of the powerhouses of European politics. This was achieved partly through military innovation and aggression (which is very much Prussia’s dark legacy; remember, even the original ‘Prussia’ was an occupied territory) but also through a process of unification and bureaucracy (the modern idea of the state is probably Prussia’s greatest contribution to civilisation).

By the 19th century, Prussia and Austria were the two dominant centres of power among the German-speaking lands. In this period both worked to suppress liberalism and socialism. Then Prussia’s dominance amongst the German-speaking people became absolute after it defeated Austria in the Seven Weeks’ War, in 1866.

This was followed, in 1871, by Prussia’s victory over France, after which Germany became a unified country under the Chancellorship of the Prussian Junker Otto Von Bismarck. Unified Germany now existed under Prussian rule and was governed by Prussian interests. It was a militaristic country, born out of war and governed by men prepared to use violence to protect their interests. Two world wars and the collapse of the idea of civilisation soon followed.

If you read about the various traumas and crises that befell Europe between 1848 to 1948 then there is a good chance that the Prussians, led by the Junkers, were involved. In that 100 year period, the aristocratic Prussian Junker class swaggered through European history, with their huge moustaches and pointy Pickelhaube hats, fighting everyone – Rhineland liberals, working class socialists, the British Empire, the French Empire, the Slavs.

Of course, there were all sorts of political interests swaggering about Europe at the same time, trying to shape history to their own ends. There were British and French imperialists. And then there were the interbred European Royal Families who, from London to Moscow, had things sewn up like the Mafia. And then there were the murderous revolutionaries, the anarchist terrorists, the anti-Semites and so many more besides. European history was littered with such villains. But amongst this multitude of villains, the Junkers still stood out. Here are nine of the ways the Junkers helped make Europe a terrible place:

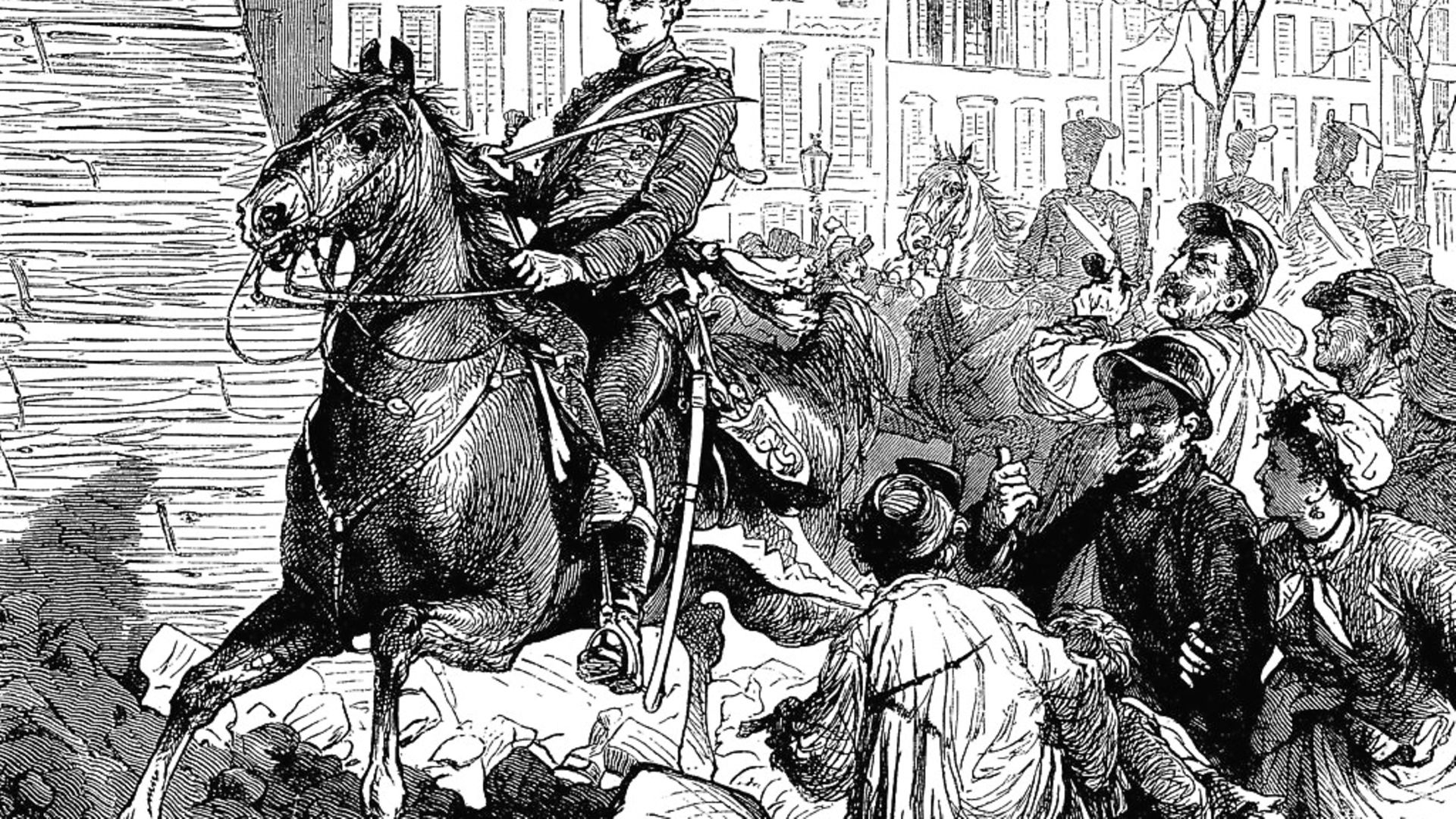

1. The Crushing of the 1848 Revolt

On May, 1 1848, Germany held its first free elections for a German national parliament. This could have been a huge moment in European history. The various disparate German states and kingdoms had, since the defeat of Napoleon, began to move towards some sort of idea of unification but various tensions – especially the tension between Austria and Prussia – meant it never happened. In 1848 a series of social upheavals and revolts swept through Europe. These were liberal, reformist, progressive and democratic in nature. In Germany, these revolts and protests lead to the creation of the first national parliament in Frankfurt.

This assembly envisaged a Germany unified under a constitutional monarchy with that monarch being the Prussian ruler, Frederick William IV. However, he rejected this proposal because he refused to accept the authority of the newly assembled parliament. In doing so he doomed it to failure; it staggered on until the summer of 1849 when it finally collapsed.

In 1949, the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (the constitution of the modern German state) was based on the 1848 version – so Germany got there in the end but only after it had taken a 100-year diversion through war, genocide, and the destruction of its cities. This devastating detour, which crushed the possibility of a better, more humane Germany, was largely due to Prussian self-interest and conservatism.

2. Germany Unified by War

The process of German unification didn’t end with the collapse of the 1848 Parliament. But now the Prussian Junkers were in charge of the process, which explains why it ultimately came through war and military conquest.

Germany became Germany in Paris. It happened after the Prussians had defeated the French in the Franco-Prussian War. It was in the Palace of Versailles where the Prussian Junker Otto Von Bismarck, who would become Germany’s first Chancellor, declared Germany to be a unified country. This was the first of three times Germany would invade France.

3. Keeping the Poor Poor

One feature of modern industrial nations is that poverty can be deliberately created. This is what the Prussian Junker class did in the second half of the 19th century. So as to protect their huge estates in East Europe they insisted on protectionism to stop cheap grain imports from Russia and the US. This forced up prices and the poor starved. One consequence was that the working class got radical. The origins of much revolutionary and radical Marxist and socialist thinking, for better or worse, begins in this period – so the Junker’s created a new enemy for themselves.

Ironically this enemy, in the form of the Soviet Union, would one day seize the Junker’s estates in Poland and East Germany and would consign the Prussians to history.

4. Fighting

That the Prussian Junkers were militaristic is a given. They had to be because the lands they ruled were at the centre of so many conflicts, conflicting interests, conflicting world views, conflicting political forces. If they hadn’t fought they would have been destroyed centuries ago.

And this is why fighting was in the Junker DNA. You can, of course, say the same is true of the British, the French, the Spanish and others – all the European powers got where they were by fighting. But Prussian militarism became distinct within Prussian culture to the point where it became the definition of that culture. The Prussian Junkers became almost a warrior class that in the end just eschewed any kind of human decency.

Here are two examples (and there are hundreds). Firstly, you have Alfred von Schlieffen, the Prussian field marshall who drew up the plans for the invasion of France which took place in 1914. To this day, people debate the reasons why it failed and it is still argued that it was a tactically sound plan. Maybe it was, but who cares? The important thing was that it wasn’t a morally sound plan. Invading other people’s countries is a terrible thing to do. This Prussian military class, with their love of military tactics and techniques, dragged the world into a horrifying war.

Another example is Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen, a cousin of the famed First World War flying ace the Red Baron, and who was also a member of the Prussian nobility. In the 1930s, in the Spanish Civil War, von Richthofen helped develop the techniques used by the Luftwaffe to integrate air warfare with ground warfare.

This was part of the Blitzkrieg tactic used so devastatingly by the Germans in the early stages of the Second World War. Tactically brilliant? Perhaps. Morally repugnant? Absolutely. The tactics involved the bombing of civilians; suddenly woman and children were legitimate targets in this new approach to total war. The destruction of Guernica, Amsterdam, Stalingrad – they were all, in part, consequences of the Prussian militaristic mind.

5. Running Away

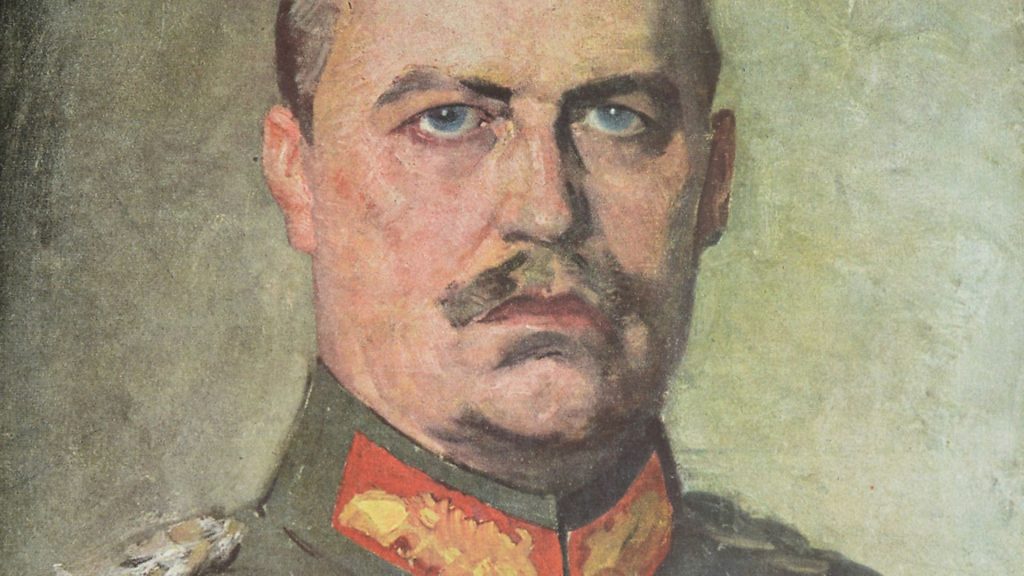

When Germany’s defeat in the First World War became inevitable General Ludendorff (a Prussian Junker) hatched a plan. At this point, Germany was effectively governed by the Prussian Junker military, but Ludendorff suggested that power should be handed back to a civilian government so that, as he put it, ‘They can now make the peace which has to be made. They can eat the broth which they have prepared for us’. In other words, they can take the blame for Germany’s defeat.

This was the birth of the ‘stab in the back’ theory so beloved of the Nazis. For the Prussian Junker and the Nazis, everyone else was to blame: the socialists, the communists, the Jews, everyone except the warmongers who caused the war in the first place. And Ludendorff got away with it. The ‘stab in the back’ theory took hold and the idea that the war was caused by the Prussian military class gradually faded away. And Ludendorff himself really did run away. He put on dark glasses and a false beard and snuck off to hide in Sweden.

6. They Supported The Nazis (Part 1)

It is important to point out that the Nazis were not Prussian and even though many Prussian Junkers would join the Nazi Party, the organisation had its origins in Bavaria. Moreover, the Nazis had to really fight for Berlin, the Prussian capital, though that fight was against the Berlin communists and socialists rather than the Prussian elite.

That said, the Prussian Junkers were mixed up with the rise of the Nazis.

In the immediate aftermath of the First World War, the right organised themselves into informal Freikorps units who continued to wage war. They fought the communists and socialists in Germany; the Poles in Eastern Europe; and the Bolsheviks in the Soviet Union. Many of these units were commanded and funded by the Prussian Junker class. The SA and elements of the Nazi Party grew out of these units. Being a Freikorps street fighter was a badge of honour in the Nazi Party.

7. They Supported The Nazis (Part 2)

Ludendorff, after blaming everyone else and running away, returned to Germany and by 1923 he was in regular contact with Hitler and the National Socialists. In November 1923 he took a leading part in the Beer Hall Putsch – the Nazi’s futile attempt to seize power. This was the closest that a leading member of the Junker class played in taking a leading role in Nazi ambitions. Ludendorff stood shoulder to shoulder with Hitler as they marched through the streets of Munich.

8. They Supported The Nazis (Part 3)

The Beer Hall Putsch failed and for a while it looked like the Nazi threat had passed. However the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s created the circumstances for fascist ideas to take hold again. The Nazis began to do well in the elections, but not quite well enough, and it was really only with the help of General Hindenburg, who was the president of the German Reich, that Hitler was able to get his hands on the levers of government. Hindenburg was another Prussian Junker general; he had commanded the German military in the last few years of the First World War alongside Ludendorff.

There are all sorts of interpretations of Hindenburg’s decision to make Hitler Chancellor – that he thought he could control Hitler, that he was losing his faculties, that he didn’t quite understand the implications – or perhaps it was just the straightforward fact that he supported someone who was right-wing and militaristic. Whatever the reason, what is unarguable was that the last Prussian Junker warlord to hold power in Germany appointed Hitler as leader and as his successor.

9. They couldn’t halt Hitler

Huge sections of the German armed forces during the Second World War were run by the Prussian military class, and, not surprisingly, they were good at their jobs. A lot of the initial military successes that came Germany’s way were down to the tradition of Prussian military leadership.

However, as the war spiralled out of control for Germany, antagonisms grew between Hitler and his generals, including many from this Junker class. This culminated in the various attempts by groups within Germany, including many Prussian officers, to kill the Fuhrer. All the attempts failed, and whilst it wasn’t just the Prussian aristocracy that were involved in these plots, the failure to kill Hitler ended up being their failure. Hitler’s defeat became Prussia’s defeat.

Failing to kill Hitler was pretty much Prussia’s last act on the world stage. With Germany’s defeat the great Junker estates were seized by the Soviet Union. All that was left now for the Prussians, that was of any use to anyone, was their legacy as warmongers. ‘Not being like the Prussians’, whilst not being quite as important as ‘not being like the Nazis’, is still an important part of why modern Germany is a responsible and stable state. Germany uses its history, in a critical way, to help shape its future – and Prussia is part of that history.

Of course, the Prussians weren’t all bad. In Frederick the Great, the so called Philosopher King, they had one of the great European leaders from the Age of the Enlightenment. He was that rare thing – a reflective and stoic leader. He had an almost ironic understanding of his place in the world. He had a belief in freedom; in the freedom of the press and in individual freedom, which, at times, was almost libertarian.

And Berlin also carries some of those qualities in its DNA. Its status as the gay capital of the world, has its origins in the Prussian Berlin of the late 19th century. Prussian Berlin, despite its militaristic swagger and pomp, could be a place of personal moral freedom. In that aspect, it was entirely unlike Catholic Munich or Cologne.

And Prussia did have an efficient state, and while much of this was geared towards war, it also provided welfare and education. This was not always entirely progressive but it was ahead of most other industrialised nations in the 19th century. And if there is one truly important positive legacy that Prussia that left to the world it is education. Prussia was one of the first countries in the world to introduce tax-funded and compulsory primary education.

These are certainly fairly significant ‘pros’ to weigh against the ‘cons’ but are they enough to rescue the Prussians from historical ignominy? Well, as far as Prussia goes, then yes. But the Junkers…?

The late 18th, early 19th century German military theoretician Carl von Clausewitz famously claimed that war is a continuation of politics by other means. It should come as no surprise to learn that von Clausewitz was a Prussian Junker. From the turmoil and barbarity of the Thirty Years War to the Soviet assault on the Reichstag in 1945, violence was, for the Prussian state and its ruling Junker class, always an extension of politics. But this was also true of all Europe. It was a continent politically defined and shaped by war, and while the Prussian Junkers were usually in the thick of that fighting, it is also true that they were just one set of players in shaping this war-ravaged continent.

Since 1945, since that moment the Prussians left the world stage, Europeans have been working towards a Europe where politics triumphs over war – and this is perhaps Prussia’s legacy. We now no longer live on a continent where war is seen a continuation of politics by other means. Von Clausewitz’s idea now seems absurd as far as European politics is concerned, and does so because the price humanity paid for the Prussian Junker belief that war is an extension of politics just wasn’t worth paying.