Former Tory activist BARNABY TOWNS speaks for many when he describes the revolution that has taken place in British politics – and among voters – since the referendum and why he will be voting Lib Dem.

I joined the Conservative Party aged 15, campaigning for it at general and local elections before I was old enough to vote. I worked as a youthful special adviser at the tail end of John Major’s government, and enthusiastically assisted with the two London mayoral campaigns of Steve Norris in 2000 and 2004. But Boris Johnson’s Conservatives are not the party I signed up to all those years ago, prompting me to cancel my membership after reluctantly voting for his opponent in the leadership election in June.

To be fair to Johnson, this has been a while coming. While Norris has a decent claim to be considered the party’s first moderniser, the Tories’ seeming indifference to his candidacy struck me as bizarre. And while the party did finally modernise under David Cameron, the Conservatives’ nationalist wing was becoming ever more powerful. This is perhaps best illustrated by Cameron’s fateful decision to hold a referendum on EU membership, announced in 2013.

Gambling with the national interest – Britain’s prosperity and place in the world – as Cameron did would have been unthinkable during the premierships of Margaret Thatcher and John Major. The fact that it is said that he didn’t believe that he would have to follow through on the promise because the 2015 election would require another coalition underlines Cameron’s recklessness. My reaction upon hearing his announcement was: look at the polling – it isn’t a sure thing that the country would vote to stay.

The 2015 general election posed a dilemma for pro-European Conservatives: Vote for a party promising an unnecessary, risky referendum, or back the pro-EU Liberal Democrats or Ed Miliband’s Labour Party, both of which opposed it. From this point, British politics deteriorated rapidly, taking a decidedly nationalist turn. Labour members elected a leader whose politics harked back to the party’s old opposition to the EU, while the Tory referendum pledge emboldened the party’s anti-Europeans.

The referendum of 2016 was a dismal affair with the ‘in’ campaign fronted by David Cameron and George Osborne, two politicians not noted for their popularity with the public, and messaging stressing the negatives of leaving the EU laced with unwise exaggerations that became known as Project Fear. It would have been a tall order to successfully make the positive case for the many benefits of EU membership after the entire political class failed to do so for decades, but this wasn’t even attempted.

Following the referendum defeat, the Tories went from bad to worse. The party faced a choice between Theresa May – who had been even less involved in the Remain campaign than Jeremy Corbyn – and Andrea Leadsom, an outright Brexiteer. Following May’s assumption of power, the Tories not only abandoned their near half-century commitment to the European project but embraced a hard Brexit removing access for the 80% of the UK economy made up of services to our largest trading partner.

May really was a gateway drug to Johnson’s full-blown English nationalist party. As someone who is as familiar with living in the United States as in the UK, I found her notorious “citizens of nowhere” speech something of a personal insult. This nationalist rhetoric and the extreme measure of pulling out of the EU’s internal market, with all the jobs and investment dependent upon it, paved the way for the party’s nationalists to oust May and replace her with Vote Leave champion Johnson.

Today’s Tories have no place for ex-deputy prime minister Michael Heseltine; former chancellors Ken Clarke and Philip Hammond; leadership contenders Rory Stewart and Sam Gyimah; sometime ministers Dominic Grieve, David Gauke, Phillip Lee, Anna Soubry, Stephen Dorrell, Alistair Burt, Guto Beeb, Anne Milton, Margot James and Justine Greening; and onetime MPs Sarah Wollaston, Heidi Allen, Antoinette Sandbach, Nick Boles, Neil Carmichael, Ian Taylor and Matthew Parris. Ex-Scottish party leader Ruth Davidson declines to participate.

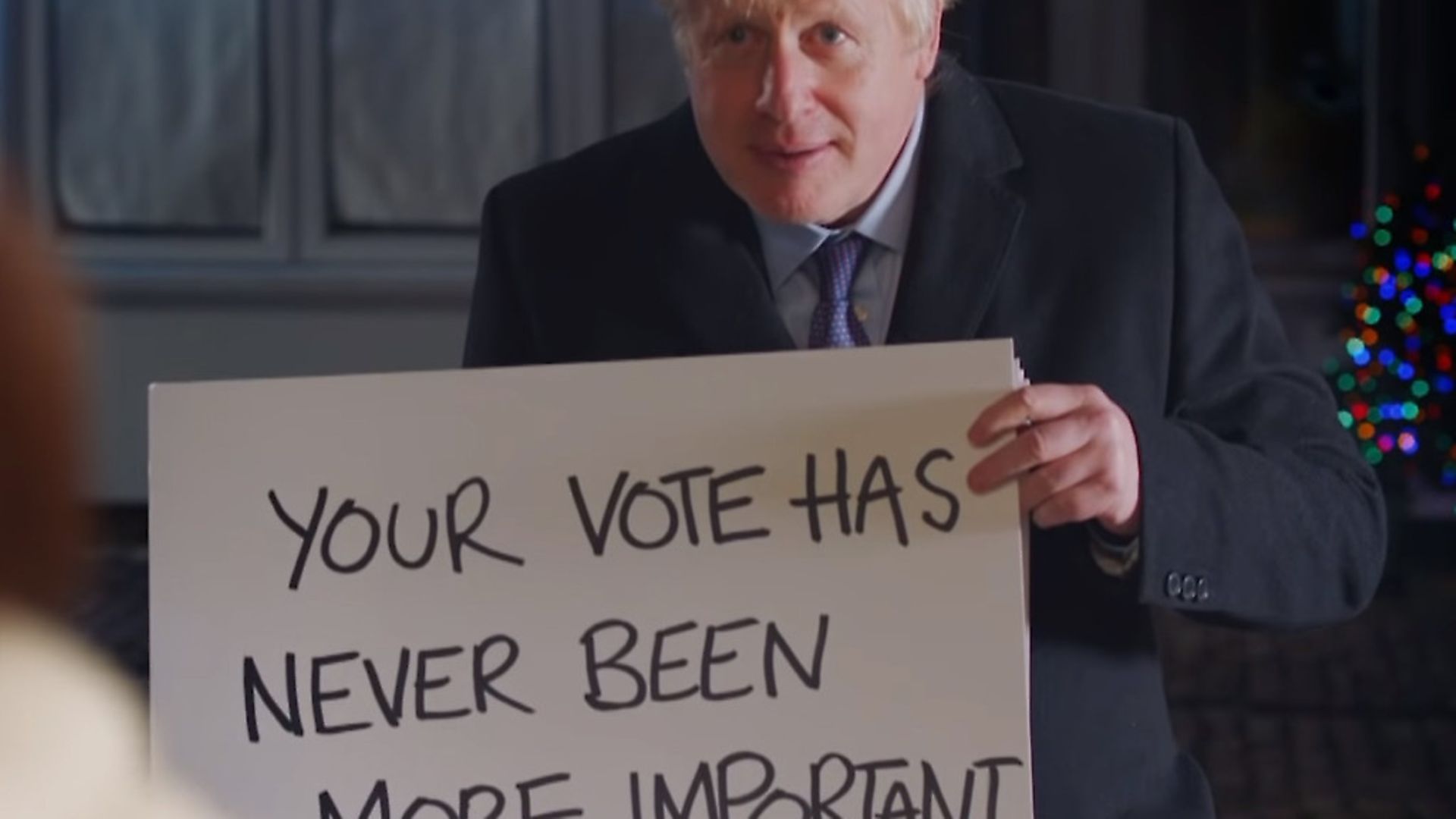

Johnson completes the Tories’ transformation into an English nationalist party. His proposed Brexit dumps May’s attempt to ensure the seamless flow of goods and her opposition to creating a border in the Irish Sea. This hardest of hard Brexits short of no deal – which Johnson still refuses to rule out – represents a revolution in Tory policy, from the old, pro-business party that inspired the EU’s giant free market and supported the Union of the UK’s four nations to a new entity that puts Brexit first.

The Conservatives have retained the brand name, but radically changed the product. For this reason, I will be joining many of the party’s internationalist pro-Europeans and voting for the Liberal Democrats.