Accepting the misdeeds of their past can be difficult for any country. Now, a provocative new book is asking Italians some hard questions about their countrymen’s role in the Holocaust. BENJAMIN IVRY reports

On September 20, the deans of all major Italian universities travelled to Pisa to apologise to the country’s Jewish community for legislation passed 80 years before.

These Italian racial laws (Leggi razziali) were promulgated by Mussolini’s fascist government from 1938 until 1943 to enforce discrimination. Italian Jews were banned from studying or teaching at universities, among other strictures. The September 20 event marks the first time that an Italian institution has officially taken responsibility for the racial laws.

Nations react differently to the revelation that at times of historical crisis, some of their citizens may have been rotters. Britain leads the way in admitting craven conduct, as described in such studies as Hitler’s British Traitors: the Secret History of Spies, Saboteurs, and Fifth Columnists by Tim Tate, published this month. Germany too, in recent decades, has conducted an extended public discourse about its wartime misdeeds. Perhaps readiness to face the past is related to lack of ambiguity about national status during a war. Britain (and its empire) was, of course, the sole obstacle to Europe being largely overrun by the Thousand-Year Reich.

Mediterranean countries, with somewhat murkier legacies, have shown less fortitude in assessing past sins. Only quite recently has France taken a sustained look at its national shortcomings during the Vichy regime.

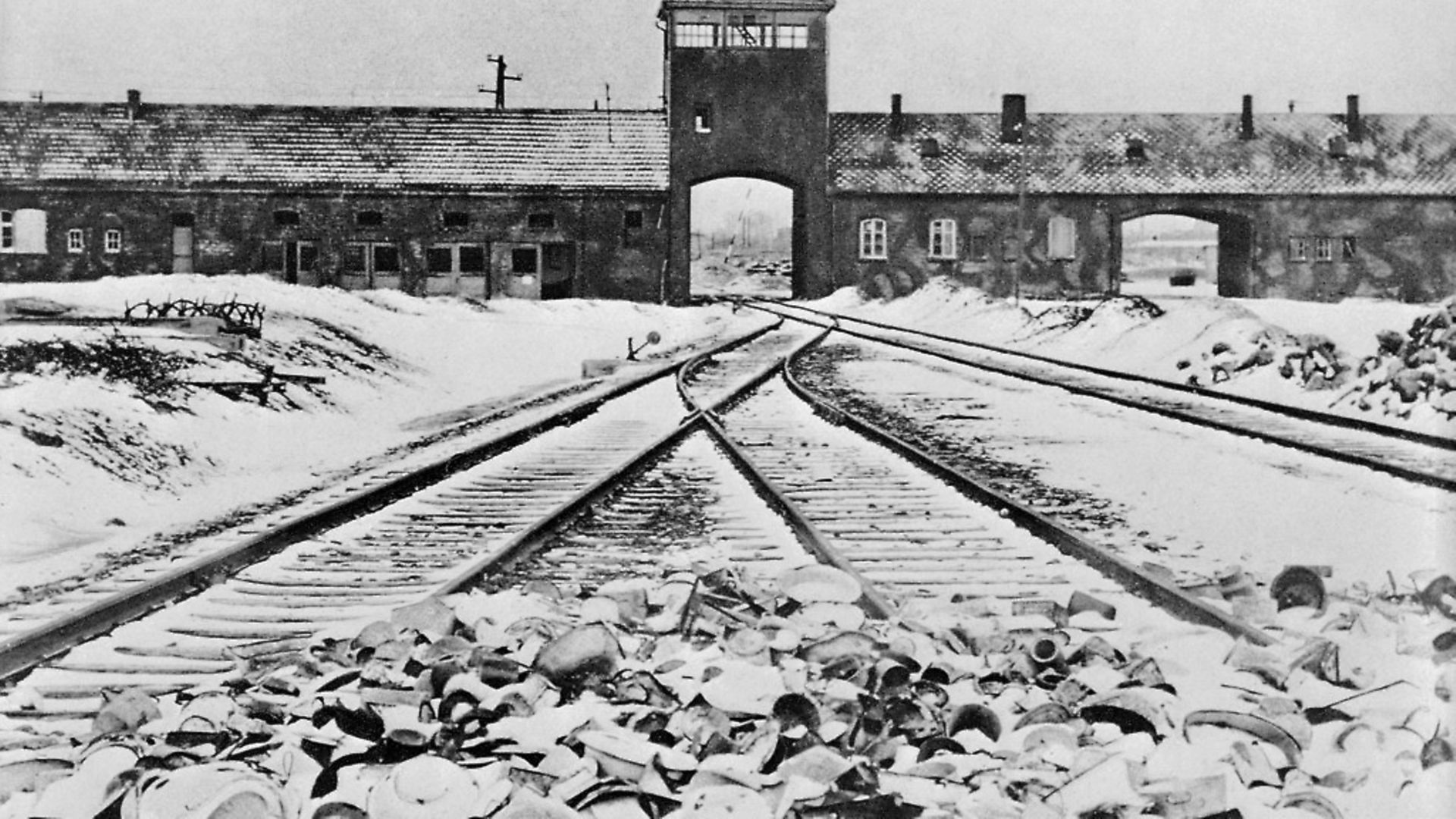

In recent years, French government officials have apologised for the nation’s actions during the Second World War which led to the deaths of thousands of French Jews. Even the French national railway system, after much international pressure, was persuaded to admit to its complicity in transporting Jews to concentration camps.

In Italy, there has been no such governmental admission or recognition. Instead, Italian state commemoration of the Second World War is limited to celebrating the heroism of a small minority of Italian resistance fighters against the German occupant. By accentuating the positive in this manner, Italian society has paid scant attention to how fascism and Nazism cooperated with civilians to eliminate Jews and other unwanted minority groups.

Enter Simon Levis Sullam, a professor of history in Venice and author of new book The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy. With admirable concision – his book is 142 pages long, plus notes and other materials – Sullam offers a cogent indictment of his fellow Italians for their actions eight decades ago.

His book’s title in Italian was I carnefici italiani: Scene dal genocidio degli ebrei, 1943-1945. The original subtitle, Scenes from the Genocide of the Jews, 1943-1945, belies the fact that the narrative is untheatrical, indeed drily factual. Its purpose is to deflate a fictional, or cinematographic, view of real-life events that cost the lives of so many.

He observes that Italy had a population of around 47,000 Jews before the war; of these, about 9,000 were arrested and sent to Nazi extermination camps after 1943. This was accomplished with the active collaboration of Italian civilians and officials. Only about 10% of the deportees survived the war, returning from such ghastly places as Bergen-Belsen, Dachau, and Ravensbrück. Yet the national narrative of wartime events has no room for the question of whether Italian perpetrators were ever brought to justice for their crimes.

Instead, the historical vacuum has been filled by films, such as the glamorous The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970), directed by Vittorio de Sica and starring Dominique Sanda and Helmut Berger. Adapted from Giorgio Bassani’s novel of the same title (1962), the movie recounts events preceding the deportation of a wealthy Italian Jewish family in the northern city of Ferrara.

Focused on elegant bourgeois life in Northern Italy before tragedy strikes, it is not a literal account of the ultimate results of Italy’s anti-Semitic policies. Even less factual are other screen interpretations of the German occupation of Italy. Filmgoers with long memories may recall the Hollywood epic The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969), in which the Mexican actor Anthony Quinn played the mayor of an Italian winemaking town. Quinn’s character, jauntily named Italo Bombolini, successfully hides a vast cellar of local vintages from the German invaders. Instead of executing him, the Nazis simply abandon the village because they are rather decent Jerries and it is that sort of film.

True-to-life accounts do exist, for those who are paying attention. Readers with even a casual interest in modern Italian literature will know about the lucid, heartbreaking books by Primo Levi, the chemist and Holocaust survivor. Levi’s highest achievements include If This Is a Man (1947), about his imprisonment in Auschwitz concentration camp and especially The Periodic Table (1975).

Although hardly a bestseller, Levi is better known outside Italy than Rita Levi-Montalcini, a neurobiologist who won the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Fired from a laboratory job in 1938 when the racial laws were passed, Levi-Montalcini survived the war by going into hiding. Her 1987 memoir In Praise of Imperfection – long out of print – is another key text for understanding what happened to Italy’s Jews decades ago.

Sullam recounts cases of Italian officials who were all too eager to facilitate the deportation of such Jewish compatriots. Ordinary civilians and professional criminals were likewise willing to denounce or extort their Jewish neighbours for profit. The notorious Carità gang was run by the fascist gangster Mario Carità, whose name in Italian ironically means compassion, generosity, charity.

Carità’s squads were euphemistically called the Department of Special Services. Among the services they provided were torturing and killing anti-Nazi partisan fighters as well as robbing and raping captured Jewish women. In 1945, Carità received his just deserts when he was killed in an exchange of gunfire with American soldiers. Yet this John Dillinger-like character is among the rare Italians who were actually penalised for their wartime conduct.

In the post-war era, most offenders benefited from blanket amnesties, as Sullam observes; by 1946, ‘almost 10,000 of the 13,000 people who had already been convicted or who were still on trial [for war crimes] were granted amnesty’.

As in France after a hasty so-called purification (épuration) of Nazi collaborators, in Italy it was concluded that everyone had better forget the recent past and get back to business. As a result, horrific memories were forcibly repressed and victims were compelled to move on with their lives, if possible. Their choice of silence was also motivated by trying to avoid further anti-Semitic persecution in post-war Europe.

The Italian Executioners contains no happy Hollywood endings, although some of its ironies might intrigue any screenwriter. One Venetian, Mario Cortellini, who ‘had supervised most of the seizures of Jewish property’ found himself after the war ‘put in charge of the Office for the Recovery of Jewish Property… The very person tasked with returning these assets to the Jews who had been his victims’.

Such odd twists of fate led to a lack of analysis of crimes committed. Nor was there much official interest in assigning responsibility for certain offences. An absence of clarity has lasted for over a half-century, despite the best efforts of diligent historians to recreate the puzzle of wartime collaboration. Only recently have questions been asked about motivation of wrongdoers. Sullam’s diagnosis:

‘The majority of Italian executioners were not necessarily ideologically motivated. The genocide was widely carried out by bureaucratic means, through police measures and actions: actions that represented political imperatives for some, for others simply orders from superiors, and for yet others an opportunity for profit or vendetta.’

A lucid, balanced synthesis, The Italian Executioners nevertheless echoes in its title the 1996 flamboyant historical bestseller Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust, by Daniel Goldhagen. Entitled I volonterosi carnefici di Hitler in its Italian edition, Goldhagen’s book was derided by historians for unorthodox use of documentary sources as well as judgments unsubstantiated by evidence. The Italian word carnefici, derived from a Latin term meaning butcher or knacker, is more charged with gore than executioner. Will the inclusion of a dramatic word in its title help The Italian Executioners to change Italy’s national approach to Holocaust commemoration?

Given how long it took the French to admit to national involvement in wartime killings rather than entirely blaming the Germans, over-optimism may be foolhardy. Caught up in a recent wave of patriotic xenophobia, Italy is unlikely to suddenly abandon the myth of a wholly righteous patria.

Italian schools still organise student trips to Auschwitz in Poland, while entirely ignoring related sites in Italy. These include Fossoli concentration camp in Carpi, northern Italy, and Risiera di San Sabba, a five-storey brick compound in Trieste that functioned as a German-run extermination camp.

Any country requires inner fortitude to look squarely at its own instances of iniquity to draw lessons from them. Despite the gesture by the university deans on September 20, Italy’s government may not be ready for any forthright confrontation with its own past.

The Italian Executioners: The Genocide of the Jews of Italy by Simon Levis Sullam, translated by Oona Smyth with Claudia Patane; is published by Princeton University Press

Benjamin Ivry has written biographies of Rimbaud, Ravel and Poulenc