JASON SOLOMONS identifies one of the films of the summer and hears from director Gurinder Chadha about how it was inspired by Brexit.

Blinded by the Light is one of the best films of the summer. A big, bright British musical movie hit, it is ostensibly about a teenage British Pakistani boy in Luton in 1987 who, inspired by the music and lyrics of Bruce Springsteen, finds his own voice as a writer. But for the film’s writer and director Gurinder Chadha, it’s actually about Brexit.

One of Britain’s most prolific and distinctive filmmakers, Chadha is still best-known for Bend It Like Beckham and her lively meshing of British and Indian movie styles and cultures. Blinded by the Light looks set to be her biggest success yet, even if it will be one tinged with sadness for the director.

“On the morning of the referendum result, I woke up as shocked as anyone,” she tells me. “But it was in the days following it that I went from sadness, to upset, to anger, all very quickly. When I saw footage, from London and all around the country, and heard stories of how xenophobia had suddenly been unleashed and vented on our streets and on our buses, I was in tears. How could we be returning to the racism I grew up with and thought we’d got rid of? I just thought: ‘What can I do about this?’ And Blinded by the Light was my answer.”

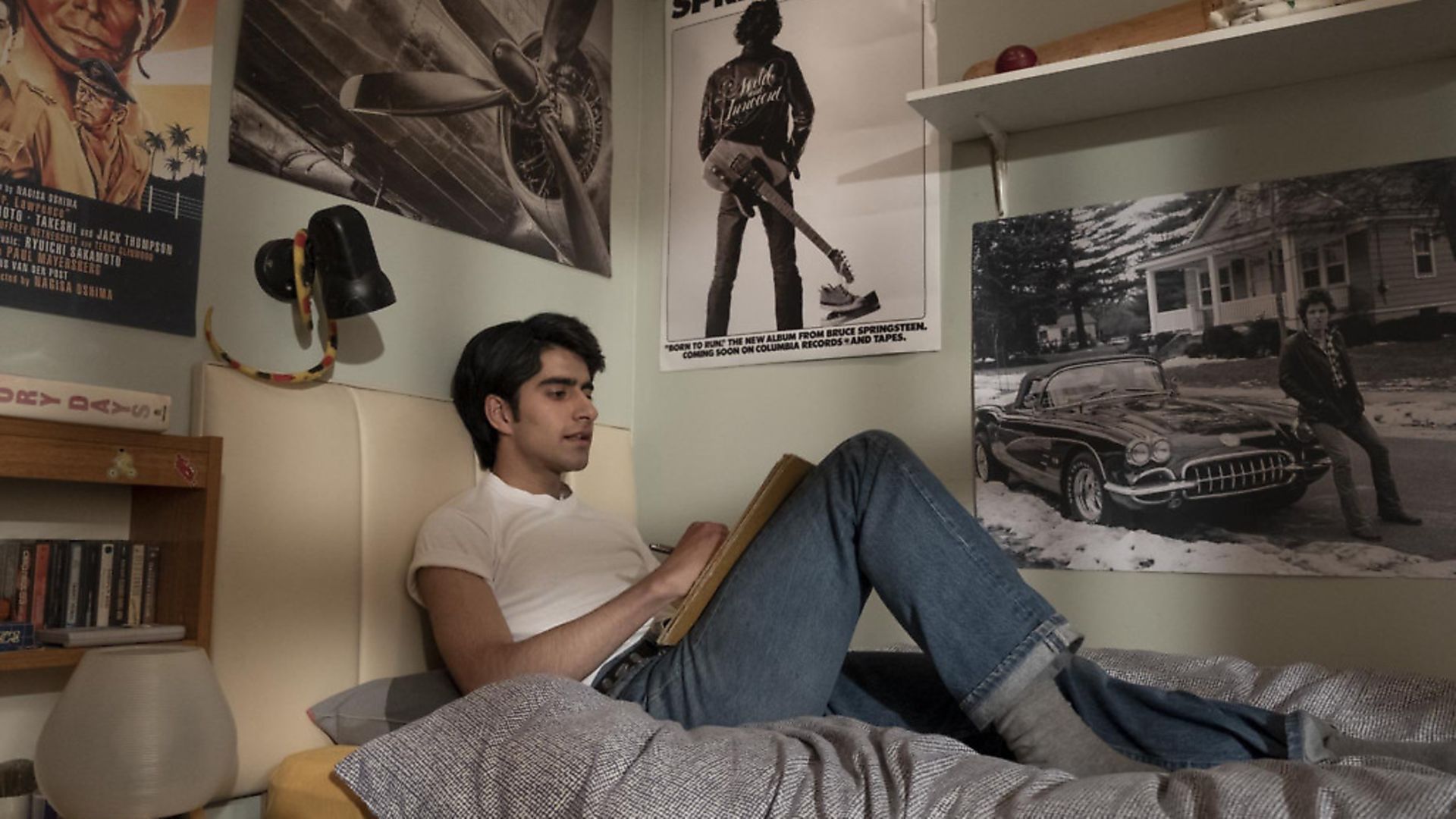

Based on a memoir by journalist Sarfraz Manzoor, the film tells the story of Javed (newcomer Viveik Kalra) who becomes obsessed and inspired by the songs of Springsteen, finding kinship in the blue collar poetry of New Jersey life that struck a chord with his own situation, stuck in industrial Luton in a Thatcher era of unemployment lines, skinheads and National Front graffiti.

Javed is also stuck in a traditional Asian Muslim family, with a father who has his son’s life all mapped out – and it certainly doesn’t involve poetry writing at college or an American singer named Springsteen. However, encouraged by Bruce’s lyrics, and by a nurturing English teacher at school (a very sweet performance from Hayley Atwell – let’s be honest, if she’d been your teacher you’d have done anything to please her, too), Javed begins writing for the school magazine.

He also begins a relationship with a girl in his class, a pretty white girl who distributes Red Wedge fliers despite coming from a very conservative house. Again, if she was in your class, you’d fancy her, too.

While Chadha’s film trades in feel-good moments and dance numbers involving market street-traders (one is played by Rob Brydon), it also contains an undercurrent of nasty racism. Skinhead boys follow Javed through his housing estate. Neighbours mumble at the presence of an Asian family in a middle-class cul-de-sac and protesters gather outside the local mosque.

There’s a superbly horrible moment where one of those long, transparent plastic mats people had to protect their hallway carpets in the 1980s becomes dramatically re-purposed to combat something nasty through the letterbox.

“I’ve never really wanted to play the race card in my career,” says Chadha. “I make films about the Indian experience, sure, but not overtly about racism. But the Brexit result seemed to open up that letterbox again. The ugliness just poured out of people and it was terribly upsetting.

“I’d just made a film called Viceroy’s House [starring Gillian Anderson and Hugh Bonneville as Lady and Lord Mountbatten] that was about partition in India and Pakistan in 1947 and Britain’s ‘divide and rule’ policy so maybe I was particularly attuned to that, but it seemed to me it was exactly what was happening again. Politicians were seeking to divide us, to encourage an ugly polarisation and that bothered me. I had to use my voice as a filmmaker to say what I was feeling.”

The film’s pertinence to today is subtle yet glaring. Chadha points out that, of course, in America the issue of Islamophobia is highly relevant and sensitive. There’s a scene near the film’s climax where Javed arrives at US immigration and one could expect that this Muslim boy might be given a hard time. “I’m here to see Bruce Springsteen,” he responds to the question about the purpose of his visit. “Can’t think of no better reason, son,” says the officer and waves him through. Everyone loves Bruce, right?

“But I was worried the film wouldn’t work in the US because it has a Muslim kid as the star and there would be either nervousness around laughing at that, or just racism resisting that. But it seems to have transcended all that and people react to the story of a son and a father.” She adds however: “I have had Muslim audience members in America come up to me in tears to thank me for putting their faces and their stories and lives up there on the screen when nobody else would ever dare.”

When filming, Chadha insisted the production was shot in Luton itself. She recalls that, despite aiming to hold a mirror up to the new tide of Brexit-fuelled xenophobia, she was heartened by how much things had changed since her own – and Manzoor’s – experiences of the 1980s of unemployment and racism. “The art department refused to spray-paint swastikas and the NF symbol. I had to do it myself – and gosh, the irony of catching myself daubing these symbols that so haunted my youth…”

Even re-creating the film’s key scenes of racial tension, the extras were less than enthusiastic about screaming racist slogans. “I had to really force them to shout ‘Ain’t no black in the Union Jack’, and ‘If they’re black, send them back’. I’d yell ‘come on, everyone’.

“These young extras just couldn’t bring themselves to say these things. I was amazed at my own ability to remember these shouts, and I shudder to remember they happened so regularly throughout my own youth, how terrorising that was. But that made me more intent on showing that these attitudes shouldn’t ever return.”

Politics aside, the film wades gloriously through the 1980s, more like an American high school movie than anything I’ve seen here, more akin to Pretty in Pink and The Breakfast Club than it is to, say Kes. It’s a film of details, of pop star posters, fashion statements, hairstyles, and crappy cars – we’re in Luton, home of Vauxhall, after all.

Springsteen’s lyrics pour out of the radio and the walkman and inscribe themselves on cul-de-sac walls and suburban garage doors, emphasising the connection between The Boss’s New Jersey working class poetry and the plight of a working class Pakistani boy in Bedfordshire’s industrial heartland, whose dad has been laid off and whose mum runs her own personal sewing sweatshop in the dining room.

Chadha’s skill here is in managing the shifts in tone, from joyous musical outpouring to racist threat and the arguments of a tight Pakistani family. More than anything, the film becomes a tussle between a teenager and his dad, who both have different ideas of the best future for the boy. That’s the universal relevance of the film, one that appeals to all families, whatever their ethnicity.

What is most refreshing is the perspective from which this thoroughly British movie comes, a memoir of an British Asian boy told by a female British Asian film maker, starring young British Asian talent. And using the music of an American legend, although there are other 1980s hits in there and some famous old Indian songs re-orchestrated by composer A R Rahman.

“My hope is that people will understand the layers that people like us, like Javed, have,” says Chadha. “We can get to tell our stories in a myriad of ways rather than being reduced to whatever the current problem is about race, like Asian actors being cast as terrorists or ogre-type dad figures. So I always want to tell stories about my community and get all the troubles and racism in there, yes, but most important is to get across all the joy, fun and the love of an Asian family life.”

Manzoor, a Springsteen super-fan on whose book Greetings from Bury Park the film is based and who wrote the first draft of the film’s script, reflects passionately on the journey his story took from page to screen, and on its ultimate power and purpose.

“What strikes me most is that audiences now know my family, my father, my mother, what my house was like growing up,” he told me. “And the hope is that the next time they see someone who looks like me, who is Pakistani or Muslim, they will see beyond the skin and not see them as different but see a human being with struggles and dreams and realise how much they have in common with them. “That journey of empathy that was the most important thing for me, with my book and now with getting this film out there. How amazing for audiences to see beyond gender, beyond race, beyond nation, beyond time to connect with the story of a boy.”

Chadha brings it back to identity politics again. “There are so many layers when I tell a story as I feel I have to look after so many constituencies,” she says. “I’m aware of Asian audiences, Pakistani, British audiences, American audiences. I have a duty to Bruce himself and to care for his music, and then there’s a global, international audience as people who don’t like or know Bruce, so it’s about that moment that music or words talk to you and change your life. All of that is in there and in me.”

As Britain withdraws from Europe, Chadha’s own experience and that of Manzoor and, of course, Javed in the film, ring out a warning. “Identity is complicated and complex and that’s why it’s so precious to people,” she says. “I can be at various times and all at once English, British, European, Asian, Punjabi, East African, West London, Indian. People like me negotiate constantly: we are multilingual and multicultural and all that layering is very natural. There are millions like me and we’ve negotiated my whole life about who we are and who we want to be.

“However, what I do know is that people who are monolingual and monocultural don’t really understand that complexity and instead feel challenged by it and they can close off to it. It’s vital to get over the nuances involved in telling the stories and showing the layers of different people’s lives. Hopefully, it can get people to think outside of their own box, not close the lid and nail it down.”