After a recent trip to Dublin, BONNIE GREER reflects on what lessons Ireland can give post-Brexit Britain.

Returning from another trip to Dublin, it is apparent to me that Ireland is ready for the ‘Roaring Twenties’.

Of course it has its problems. That, no one can deny. For example, one of my previous visits brought me face to face with a young Irish woman of colour who told me about the discrimination she faces, the assumptions made about her because of the colour of her skin. On another, a woman told me about her country’s assumption of male privilege.

And, like other places, many of the citizens of Ireland are not participating in the surge in wealth that tech is bringing to the country.

Equality of wealth creation is the business of politics and what politicians must do. But there is something else politicians must do, too. Something else that has to do with a sense of what the world is about and the place their nation has in it.

The flight between Dublin and London is not long. But the Irish Sea is more than just a natural divider. The across it presents the question of the mid-size nation-state. Where does it fit now in this turbulent world? What does it do?

A nation is like a grand house. It must present itself in a way that makes it look worthy of its status, its reason to be.

Ireland was born, in some ways, in the street. The Easter Rising was a reaction and an action, both geared towards ordinary people. They fought in the public square. They fought for freedom. So the grand house that is Ireland is about, above all else, freedom.

The absurdity of the subtext that the UK directs towards it in matters of politics causes the nation to always have to take a position in relation to its former coloniser. This has to be exhausting and boring.

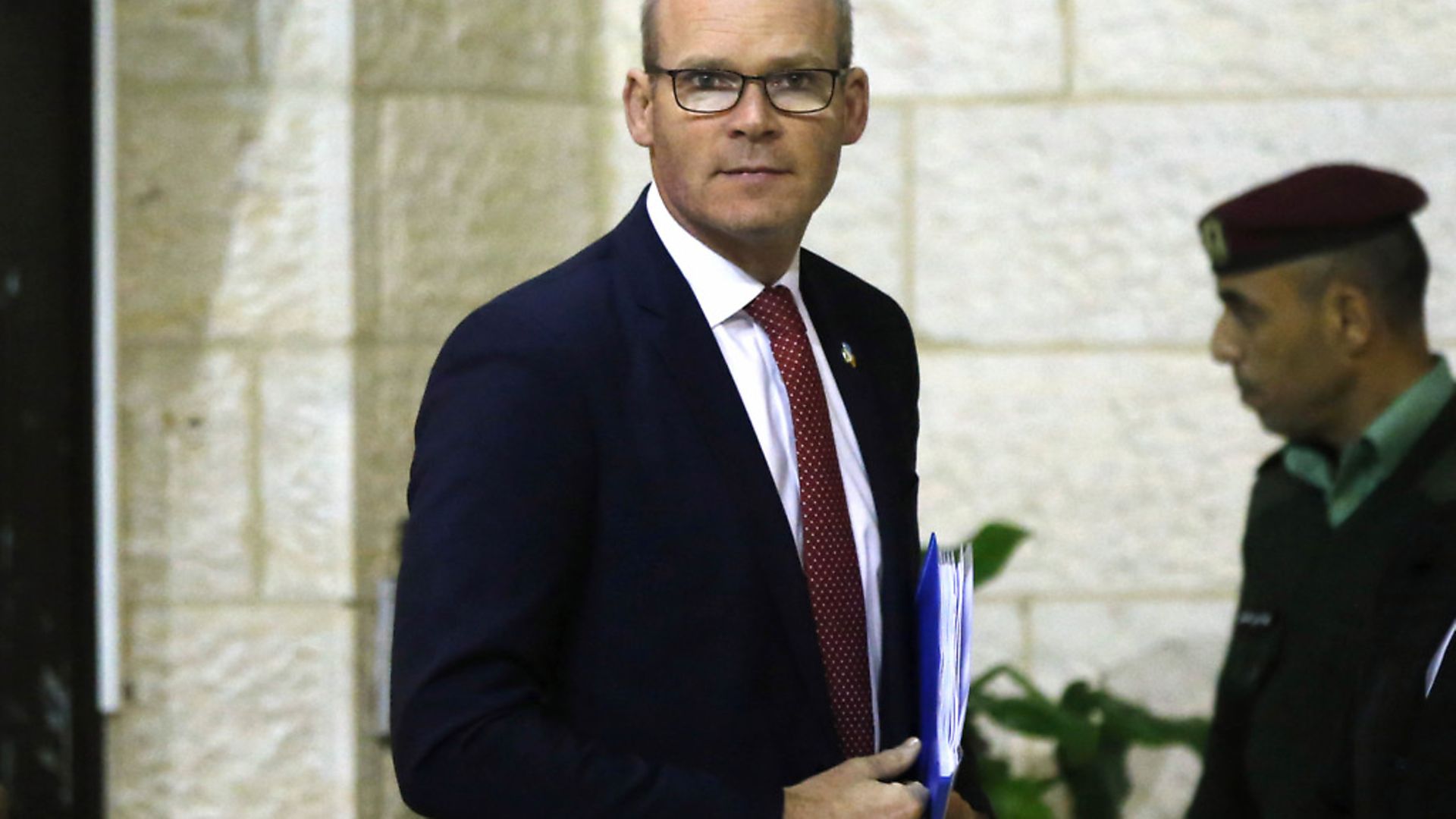

Of course, the UK still has part of itself on the island, in the national space. That is another question. But can the very presence of Britain serve, in a sense, to make the nation stronger? Yes, and this strength is demonstrated by its formidable foreign secretary and deputy leader of the country, Simon Coveney.

Someone tweeted to me once that there is nothing nice about a man from Cork. I don’t know what that means, but niceness is not required in his position. Clarity and a sense of where his country stands in the world is. And Coveney is second to no one there. He is the best foreign secretary right now in the world.

At the weekend, he told the BBC’s Andrew Marr Show what should have been obvious: that there is no guarantee that the UK will be able to strike a trade agreement with the EU.

“Just because a British parliament decides that British law says something doesn’t mean that law applies to the other 27 countries of the European Union.”

He added: “The European Union will approach [its negotiations with the UK] on the basis of getting the best deal possible, a fair and balanced deal, to ensure the UK and the EU can interact as friends in the future. But the EU will not be rushed on this just because Britain passes law.”

This may seem like an elementary point. But with the landslide that the Conservatives won last month we are other territory. It’s a bit mystical.

I have been told constantly by elements of Twitter world to be kind; to tiptoe quietly around Leave supporters lest they perceive that I accuse them of being deluded or stupid or worse.

It is as if Remainers are expected to sit back, be docile and accept the result. I have never thought that being docile about what you believe in is very British and, besides, Brexit is a process. A journey.

Ireland presents the UK with a possibility of a reality check. Ireland can broker with the US Congress, for example, in any trade deal with Washington. Since most people know that the president only makes a temporary deal, and that the Congress ratifies, the UK will need friends. Trade with the US involves each of the 50 states, which are sovereign through the lower House. In other words, various trade bodies, lobbying groups and so on appeal to their representatives in Congress about ratification.

Nancy Pelosi, speaker of the House of Representatives, has already warned the Congress would block any deal between the US and the UK which threatens peace in Ireland: “The peace of the Good Friday Agreement is treasured by the American people and will be fiercely defended on a bicameral and bipartisan basis in the United States Congress.” In other words: IOTUKN, Ireland owes the UK nothing.

But in this ‘Festival of Brexit’ moment, it seems to be very difficult for those who govern the nation to face reality. The reality is that Brexit and trade deals will take years. In the meantime, what will Britain do?

It can watch Ireland, watch how it positions itself as a medium-sized state in a global world. It is not doing things perfectly. But it understands itself in the Big World. It understands itself on a global stage. And maybe it can teach a post-imperial nation, a medium-sized nation, an ageing nation, how it can be, too.

What some call the most pillaged poem in the English language, Yeats’ The Second Coming contains these lines:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Maybe this poem is more about Yeats’ mysticism. Maybe it is about another century: the 19th. Maybe it is more about the poet’s own feelings about the doom of Western civilisation following the First World War.

But as I was taken on a tour of the great Abbey Theatre on an earlier visit to Dublin, I thought about this temple to theatre, and the fact that the nation had formed itself culturally before it did politically. In other words, the Abbey Theatre existed before the Irish Republic. It came into being to dream the nation.

If the United Kingdom can bury its inherent imperialist attitude/response to the Republic, then Ireland has lessons to teach.

And maybe a way of helping Britain settle into its new place in the world. As one, among many.