BONNIE GREER uses television to examine and investigate what it means to be ‘English’.

Among the consequences of living in lockdown are the things that you suddenly see. That you suddenly know.

For example, I have come to realise that I have been a Londoner for longer than I lived in the city I was born and grew up in, Chicago.

Unconsciously, I think, I have spent most of my time not only looking at Londoners, but dissecting the English. Or rather what the French call l’Angleterre profonde. When you live somewhere and haven’t any roots there, on an unconscious level you are always investigating, always looking around. Listening.

During this lockdown I have brought this activity to the surface – my scrutiny, my dissection of ‘England’. Not the real England, the authentic thing, but the entity that is sold abroad and to those in this country too. This is the entity that largely accounts for the success of Julian Fellowes. And not only him.

Now I can see that part of me lives here as if I’m watching a film, sitting back in a darkened theatre, observing.

The United States is natural to me: I understand, in a rather horrible way, why Michigan protestors against the lockdown went to their State House armed with guns and waving flags. To the outside world this looks appalling. And it is.

But, in a sense, this is a literal manifestation of what Americans think they are and what they think the country is. It is the movie running inside each American, a blockbuster starring themselves. And this is the ‘American Dream’. It is the old cry of ‘give me liberty or give me death!’ which every American carries somewhere inside them, too.

To be an American is about exceptionalism. Americans do not have things happen to them the way that others do. The US is the exception to all rules. Many Americans, deep down inside, truly believe that the Covid-19 virus will skip them, if they only believe, that somehow it will all come out alright in the end, like in a Tom Hanks movie. Just have faith.

Of course, Americans can see the racial, health and economic disparities which this pandemic has revealed. But to be American is about who you are. What you want to do.

Doctors can yell and scream and hold up all kinds of statistics. But in the end, every American is Dorothy on that yellow brick road clicking the heels of those ruby slippers together. For Trump’s base their response to the president’s lying and constant moving of the goalposts is ‘so what? He’s allowed to dream, isn’t he?’ If you don’t dream metaphorically, you are not an American. And besides, Trump was a real estate mogul and reality show host. And now he’s president of the United States. So all things are possible in the USA. Right? That is America. That I get.

I also get Andrew Cuomo, governor of New York sparring with his younger brother Chris, the CNN anchor about who their mother really loves. On live TV. This is what the country is.

But what has come to my consciousness lately is that I watch television to discover England. Not the real place. But the myth, the thing it thinks about itself and wants to show to the world.

First, I have become dedicated to the historian and broadcaster Michael Wood. He has made me a fanatic regarding the Anglo Saxons, those utter geniuses who made their way over here from what is now Germany and the Netherlands. The roots of the English language are largely their invention.

The language originated in Anglia, a small Baltic peninsula in Southern Schleswig, in what is now northern Germany. You can hear Old English spoken on Wood’s excellent series of documentaries. You can also hear the accent of the forerunner to modern English, the tone and emphasis of which has a distinct Dutch/Germanic sound.

The English have always liked kings and queens, and the Anglo Saxons had Alfred the Great and his daughter, Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians, sovereign in her own right as was her daughter who succeeded her. I think that deep inside somewhere, the English are not at all averse to women ruling them.

But even Michael Wood cannot hold a candle in the dissection of l’Angleterre profonde found in the works of Dame Agatha Christie and in the long-running detective series Midsomer Murders, particularly the latter series starring Neil Dudgeon.

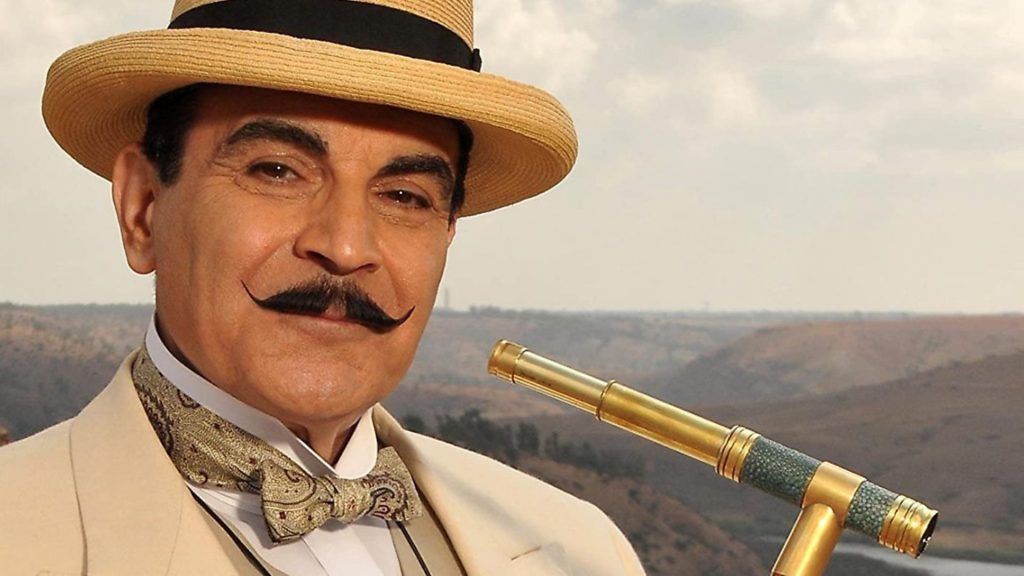

In Christie’s novels featuring Poirot, and the television adaptations, you find plenty of references to the Belgian detective with the steel-trap brain being a ‘foreigner’. Even when he has become the most famous detective in England, Christie does not allow the English to raise him above suspicion. The greatest insult hurled at his prowess is that he is a foreigner and he must constantly correct the English who consistently call him French.

The novels and the television versions are beautifully observed in relation to the English class system, from parlour maids to duchesses. The killer is almost always someone whose ‘Englishness’ drove them to murder. Common motives include anger over being left out of a will, reputation, revenge, or just plain status. All England is here.

Midsomer Murders represents a modern version of this. Midsomer is a mythos place, set in villages in what feels like the Home Counties. Even the Queen is a fan.

One episode that deserves every reward going regarding Englishness is about a murder concerning a craft beer named after a friar executed in the 14th century. The modern day Midsomer victim is killed in exactly the same way as the medieval friar, plunged into boiling oil. Sheer English village genius.

Suspects there are now an ethnically diverse bunch of English people who pop in and out, having committed various deeds. Mostly in secret. Secrecy being an ace English trait that both Christie and the Midsomer team employ magnificently.

Midsomer is the opposite of the Inspector Morse series, which, with its spin-offs, is a kind of ‘Via Dolorosa’ of Englishness. And this is seldom interesting, except perhaps in the poems of Philip Larkin. My lockdown has become a kind of research tool, a way to understand parts of my adopted land and its people, at the deepest level. It helps me understand things like why Boris Johnson is PM; why Piers Morgan has a job; what Britain’s Got Talent really means, and Only Connect, too. This is a show I once did to aid charity and sat there thinking that it made no sense. Which is the entire point.

Oscar Wilde once called the fox-hunting English aristocracy ‘the unspeakable in full pursuit of the uneatable’. And even though fox hunting is banned, some of the English have found a way for it to survive. Survival is a great English trait. An example of this is what the grandson of Queen Victoria did. George V launched arguably the greatest re-branding exercise of the 20th century. His decision to change his family name from Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, to its principal place of residence, Windsor, was a masterstroke. No doubt Poirot would have suggested doing this. After he had finished investigating a murder in the quiet grounds of Windsor Castle.