BONNIE GREER looks back on the life of activist John Lewis and his fight for equality.

A book that I wrote but never finished is called The Radiant Day: The Story of The March on Washington, August 1963.

It began by looking at some of the leader figures involved in the event: ‘In August, 1963, Bayard Rustin is 51 years old. James Baldwin is 39 years old. Martin Luther King Jr. is 34 years old. And student leader John Lewis is 23 years old.’ The first three of those men have been dead for several decades. Lewis died earlier this month after a six-month battle with pancreatic cancer, at the age of 80.

The hardest thing about being alive for a long time are the aches and the pains… of history.

You have to endure what feels like the complete ignorance of history itself, the deeply ahistorical reality of most people; the belief by the young that the past was a failure. And that they alone can rectify it. But you know that you once believed the same thing, too. Human nature.

But I was lucky at my university.

We students back then were enraged by the election of Richard Nixon. We blamed this on the so-called centrists of the day who had de facto colluded, as far as we were concerned, with the right.

In those days the motto was: ‘Never trust anyone over 30.’ That gives you an idea about what 30 years old was perceived to be like half a century ago. We babyboomers believed that we would overcome them. Everyone. And we did.

But this is not the point. The point is that we still paid attention to what had gone before. We knew about it. Plus we had profs who were not cowed by us; not full of apology for their education, their point of view.

Notwithstanding this, we invaded their offices anyway; ransacked their files; shut down their classes and their universities. We yelled at them in class, too, but they taught us anyway; taught us history anyway.

Maybe what they taught was just the bits that they wanted us to know. But if we were not too lazy, nor too stupid, nor jaded, we explored further. And we saw history on TV and knew what it was.

One thing that my history prof, Dr Turner, told us was that Richard Nixon would disgrace his office. He documented Nixon’s trajectory, as congressman from California, then vice president to Dwight Eisenhower, on to the late 1950s when many of us were old enough to understand a tiny bit about the world and that it did not revolve around us.

The world was television; we were the first media-orientated generation. The first president we were ever conscious of was assassinated live on lunchtime telly while we were at school. And we watched the civil rights movement on TV. We watched almost the entire arc of it until it no longer spoke to us.

It no longer spoke to us because if the old had done things right, there would be no need to march. We knew that we were right. The movement was our big brothers and sisters, and mothers and fathers, and aunts and uncles out there. Old people. What the old do never speaks to the young. Which is probably as it should be. But the bad thing about that is that stuff is done over again and over again until people forget that stuff actually ever happened at all. And then the people are back at ground zero. But John Lewis never was.

He carried on from what had been created in the past. He lived and he made history.

Lewis was born in Alabama in 1940 and grew up in the state. He first heard Martin Luther King Jr’s voice on the radio one day when he was 15, and decided that this was a clarion call to his life. Later that year, he closely followed Dr King during his ultra-daring Montgomery bus boycott, which propelled him to national prominence.

Lewis became dedicated to non-violence and civil rights, and organised sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville, Tennessee. He helped de-segregate them, which meant that if you were African American you could finally sit down and have a cup of coffee instead of being ordered to leave or be served outside in the street.

Lewis was arrested many times and jailed, and jail was not where you wanted to end up if you were African American and in the South.

He was outspoken and never allowed anyone to shut him up. His goal was to make what he called ‘good trouble’ – the kind that led to justice.

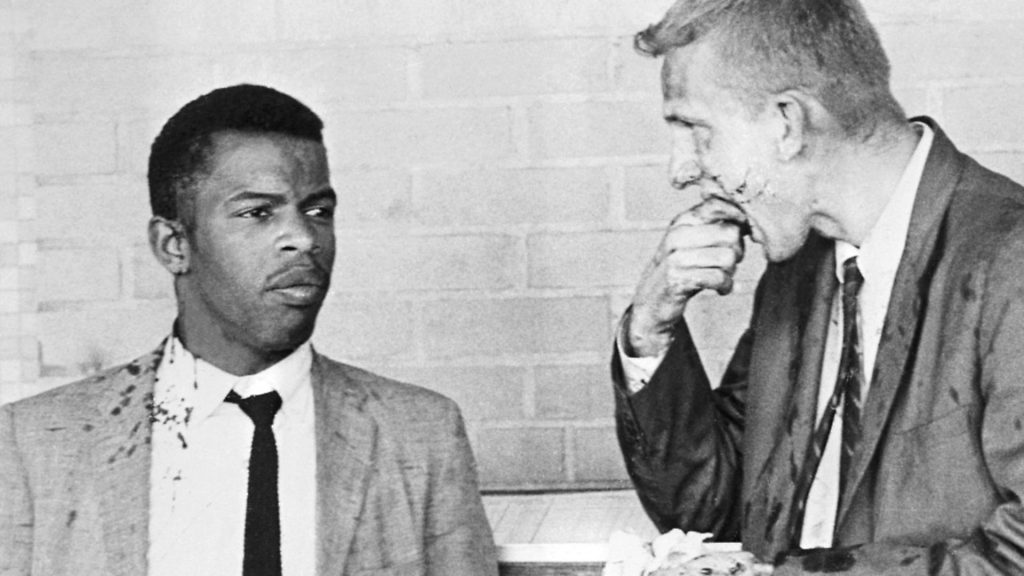

In 1961, he became one of the original ‘Freedom Riders’, the fount of some of the anxious moments of my late childhood and early adolescence, as their activities became a staple of the evening news.

The Freedom Riders were white and black students who rode interstate buses into the segregated South, where laws still prohibited black and white passengers from sitting next to each other on public transport. Being the child of a Mississippian, I knew how dangerous their journeys were.

Lewis was beaten up and, at times, arrested. The amount of violence he endured was appalling. He faced baseball bats, chains, lead pipes and stones. He was beaten unconscious on one occasions and left lying at the Greyhound bus station in Montgomery. Decades later, a former Klansman involved in the violence against him apologised to him on television. ‘It’s OK. I forgive you,’ Lewis immediately responded. That was the kind of man John Lewis was.

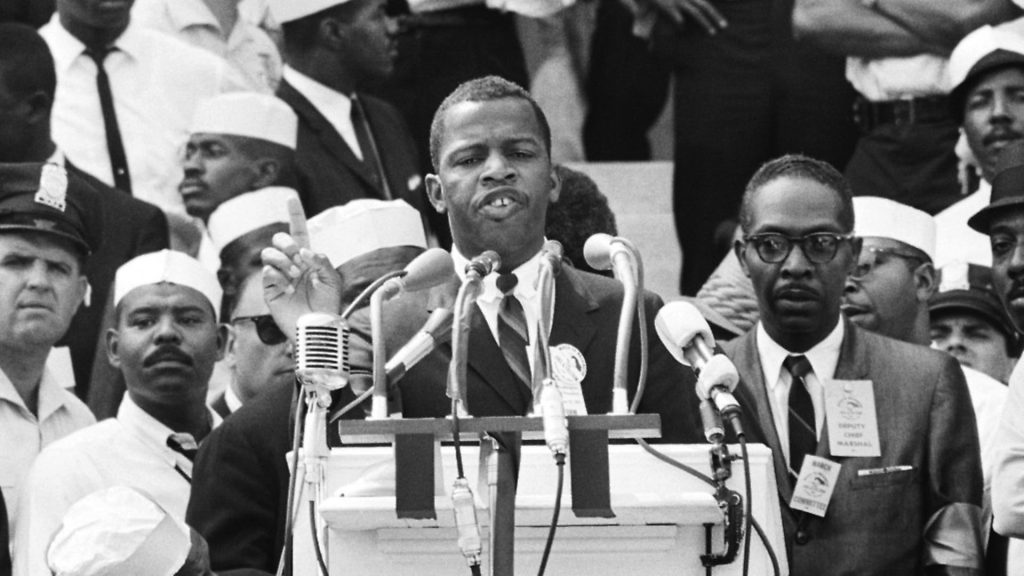

While researching my book, I discovered that the March on Washington almost never happened. The organisers were not sure that anyone would show up. Plus this was an event that was going out on television in the afternoon. The TV schedules were cleared. There were lots of anxieties behind the scenes. Some of these were about Lewis. The various organisations involved were worried about what he might say.

He was fiery; he had been through hell; he was young and who knew what would happen when he gave his speech.

Before he delivered it, he had to submit the wording to the organisers. His line ‘Which side is the federal government on?’ was removed, so as not to offend the president and his brother, the attorney general. A line still had to be walked.

Lewis was the youngest speaker on the day and, at the time of his death, the last left alive.

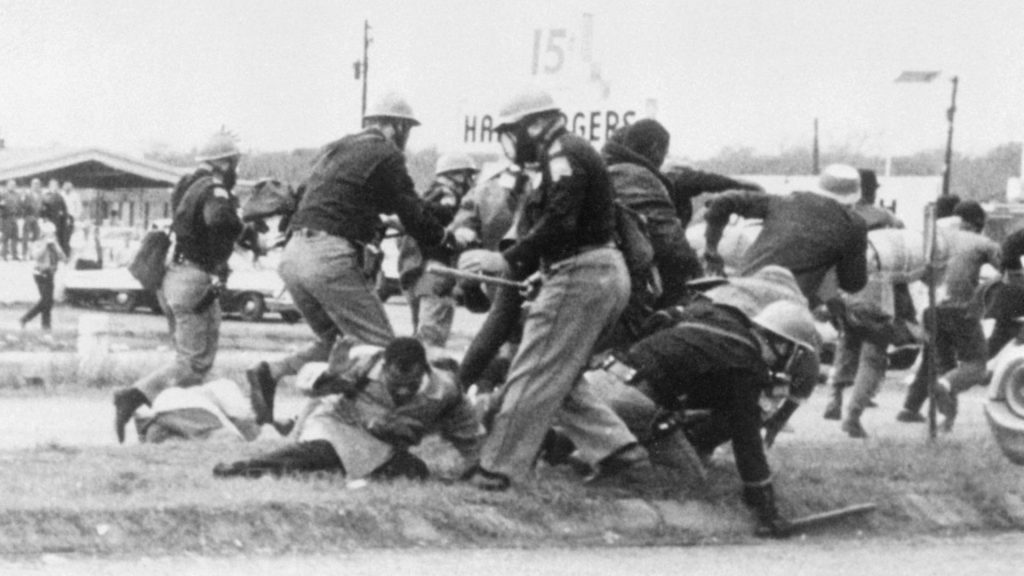

Two years after the March on Washington, on March 7, 1965 – America’s ‘Bloody Sunday’ – Lewis and fellow activist Hosea Williams led more than 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

This was the first attempt to stage a march along the 54 miles from Selma to the state capital, Montgomery, to demand the right to vote for black people.

As the marchers crossed the bridge they encountered a wall of state troopers, who ordered them to disperse. When they did not, they were tear-gassed, charged at by mounted officers and beaten with night sticks. Lewis’ skull was fractured and he carried the scars for the rest of his life.

It was scenes like this that led my generation to choose the option of the Black Panther Party; urban uprisings and a generational ‘no’ to non-violence.

Later, many did what most people do: get a job; have a family; buy a house, settle down. But Lewis really never did. He continued with his commitment to non-violence and ended his days as Democratic congressman for Georgia’s 5th District.

Considered the conscience of the House of Representatives, he served his district and his country there for 33 years.

To high and low, old and young, he always spoke truth to power. There was no alternative, for John Lewis, to that.

He was a champion of LGBTQ rights. And for national health insurance for everyone. He wrote a graphic novel for young people about his days in the movement so that they would know and not forget. All of this and more was what he called making ‘good trouble’. ‘Good trouble’ was who John Robert Lewis was.