As things begin to fall apart Bonnie Greer looks back at the late great writers who will define the next 12 months.

Three writers come to mind at the beginning of this momentous year: two who seem to echo the potential feelings and crisis of 2019 – W. B. Yeats and F. Scott Fitzgerald; and one who may have a kind of remedy – Voltaire.

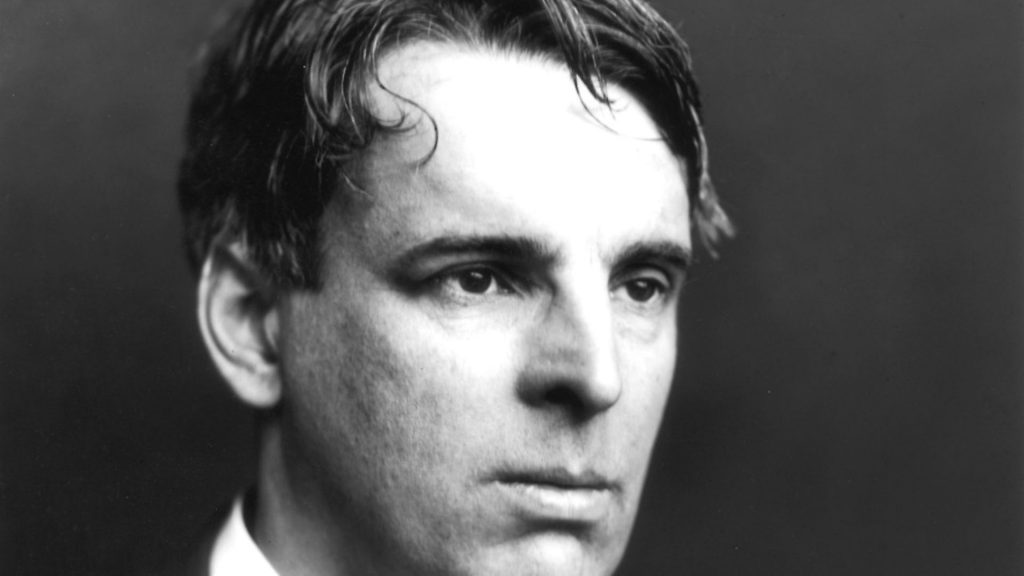

One hundred years ago, Yeats – mystic, poet and son of Ireland – wrote his ground-breaking masterpiece The Second Coming, containing the oft-quoted line:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.

The ‘world’ Yeats describes is the post-war one of 1919, a year in which the destruction of an old world became visible. Real. That hegemony of a kind of reason and sanity; of ‘place’; even of God; was slowly becoming unravelled. Perhaps it never really existed.

For those under the colonial yolk, for women, for artists, it was the beginning of a long process of liberation that is still ongoing. But something was disintegrating too, even as the new was being born.

Yeats felt, as only great artists can, what was in the wind. It was not necessary to name it, but part of what was to come is hinted at in the line: The ceremony of innocence is drowned.

As he wrote, his country was claiming itself back: the Dáil Éireann met for the first time in 1919. It assembled in Dublin and included Sinn Féin representatives, elected in the 1918 general election.

As stated in their manifesto, they refused to take their seats at Westminster and instead declared an independent Ireland. The Irish War of Independence stepped up with Sinn Féin’s election and who can say that this war of independence has ever stopped? That so few of us understand Ireland or care about it, cannot see its integral link with Europe, its need and passion for that connection – and Europe with it – is a tragedy of ignorance and something worse: dismissal and disdain. ‘Brexit: la revanche de l’Irlande’, the distinguished journal L’Histoire headlines on its current cover.

As the poet contemplated the post-war world in 1919, he found the words to ask the question:

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

In 1919 the ‘beast’ came to be. And an evil absurdity, too. Benito Mussolini founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento. The Fascists. He also began formulating a foreign policy which he called spazio vitale (‘vital space’), later copied by Hitler.

Mussolini believed that Italy had to, for its survival, contain the entire Mediterranean region. The Italy he wanted to ‘cleanse’ was full of unclean, violent and alien peoples. He later invaded and colonised Ethiopia in a violent and ridiculous show of recreating Imperial Rome. He saw Italy overpowered by a plutocratic, overbearing entity that stymied his country’s growth. That entity was Britain.

This notion of an overbearing entity, of a monster out of control and unaccountable, is roughly the same argument that Matteo Salvini, Il Duce fanboy and the current deputy prime minister of Italy, makes against the European Union and against immigration in general.

There are fears that he and his ruling party could stage its own version of Mussolini’s Marcia su Roma, or March On Rome. Salvini has even used the name itself, knowing full well that it is a national dog whistle meant to be a threat to the establishment. That Salvini himself is the establishment seems to be overlooked. Above all, by himself.

In the United States, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s essay The Crack-Up, a contemplation of the wasted promise of his youth and written in the 1930s, seems to be one of the essays of the moment now. It contains the phrase: ‘The test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function. One should, for example, be able to see that things are hopeless and yet be determined to make them otherwise.’

Another line is: ‘Life was something you dominated if you were any good. Life yielded easily to intelligence and effort, or to what proportion could be mustered of both.’

These are very American notions, natural ideas that now seem to many in the USA to be the statements of a bygone, optimistic age, of a kind of juvenile time.

In 1919, Fitzgerald’s first novel, This Side Of Paradise, was accepted for publication and published the following year. He was almost 24 years old – young, like his nation, and full of power and promise, like his nation, too. But Fitzgerald lived in an America at war with its president. Woodrow Wilson faced a dilemma: the USA wanted to turn its back on the world.

Refusing unitary command under the French during the war, the nation’s elites now demanded that America not join the nascent League of Nations. America was in retreat; afraid of foreigners and immigrants. 1919 was a year of race riots; of the internal migration of African Americans from the rural south to the industrial north. Evangelicals and some suffragettes came together to create a constitutional amendment to ban alcohol. In their attempt to do ‘the right thing’, they practically criminalised almost every adult in the country.

The golf-loving Warren Harding was elected president in 1920. His slogan encompassed the idea of what he called: a return to ‘normalcy’, a mathematical term which can be interpreted as the 1920s version of ‘Make America Great Again’. He rejected the ‘coastal elites’ of the day in favour of holding what he called ‘front porch’ rallies in the Midwest. There he vowed to return the US to greatness. After Harding dropped dead of a heart attack, the corruption of his administration was discovered. The populist had played the people.

One of the answers to our time, to this growing damage to public life, to rationality itself, is ridicule. Not ‘ridicule’ in the Anglophone sense, but in the French sense of the word: a deep and profound exposition of the absurdity of tyrants, ‘strong men’ and those in charge of our destiny who attempt to rearrange common sense, even reality itself.

Ridicule, in this sense, exposes Jacob Rees-Mogg, Nigel Farage and John Redwood, for example, as men of privilege masquerading as champions of the people. It exposes the dangerous absurdity of a billionaire who emerged on an escalator from a gilded tower to announce his candidacy for president of the United States, professing to have the interest of an Ohio steelworker uppermost in his mind.

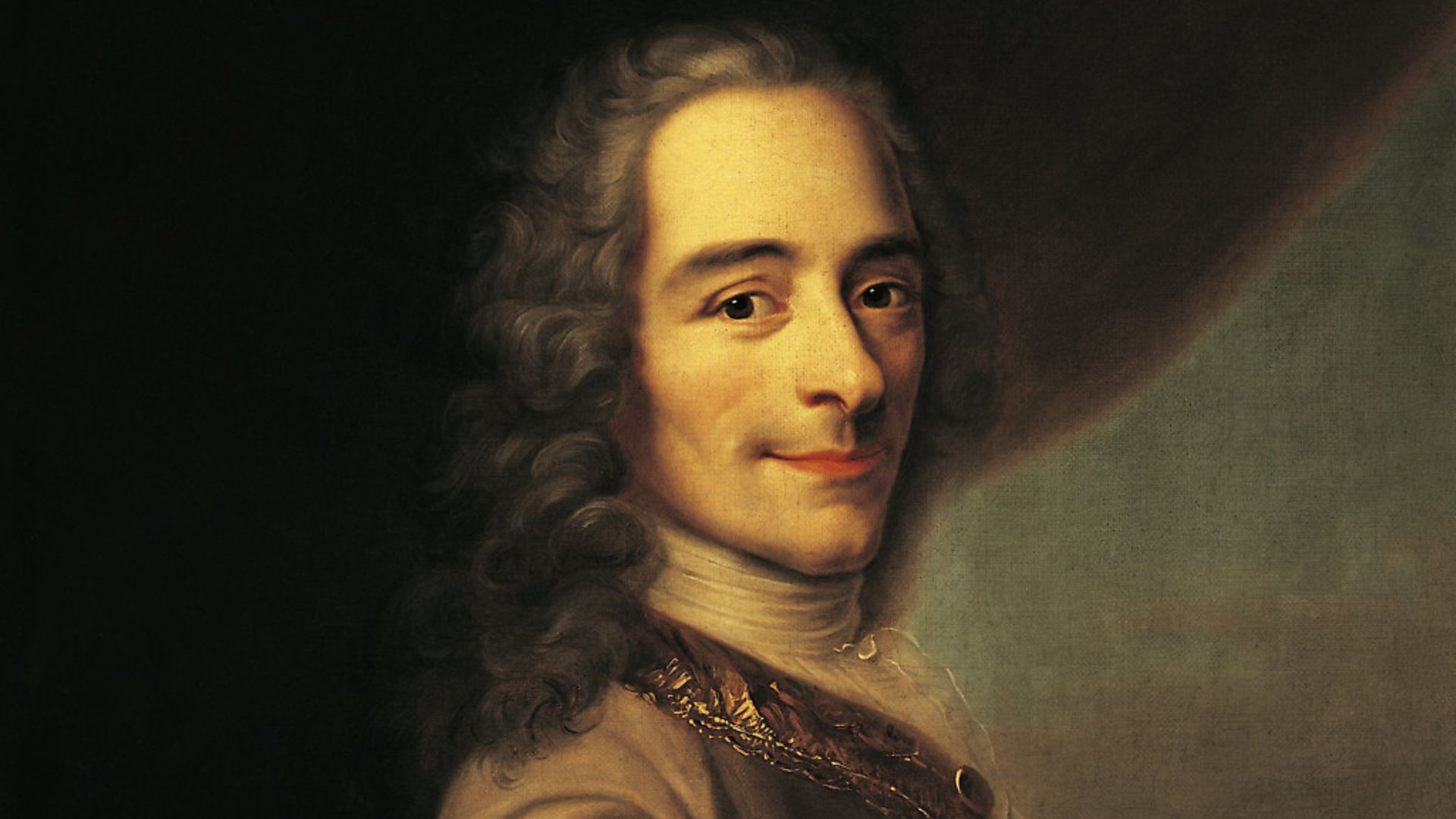

The man who used ridicule, who changed opinion in his time, who helped usher in another way of looking at the world and those in power was Voltaire.

He was a pillar of the establishment, but a rebel against it, too. He saw the absurdity of many in public life. And of those who would die in the ditch for a political philosophy. Whether it made sense or not. ‘Ridicule is a powerful barrier against the extravagances of all sectarians,’ he wrote.

It is clarifying, too. Voltaire challenges us to tell it like it is. Which is what true ridicule does. And what 2019 needs – to be the Year of Ridicule.