Even on the military campaign and whilst in exile Napoleon remained a voracious reader; Ray Cavanaugh delves into his reading list 250 years after his birth.

Whether one views him as a military Einstein or a Frankenstein of ego, Napoleon Bonaparte was an ardent reader of books.

His bookish tendencies surfaced at an early age, while he attended military school in France. Soon, he was reading French translations (French was actually the third language of the Corsican-born Napoleon) of the ancient scribes Arrian, Plutarch, and Polybius.

A more modern book that resonated with the highly ambitious youth was Alain-René Lesage’s Gil Blas, a tale of an impoverished Spanish boy who, by dint of his intelligence and willpower, eventually rises to the position of secretary to the prime minister. Biographer Vincent Cronin related that the first thing a 15-year-old Napoleon did upon coming to Paris (where he attended the École Militaire) was to purchase a copy of Lesage’s novel.

From the beginning to the end of his adult life, Napoleon was fond of the Ossian cycle of epic poems, which were published shortly before his birth by the Scottish writer James Macpherson.

Unsurprisingly, Napoleon was also well-acquainted with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, though he had a rather mixed estimation of the Enlightenment philosopher’s works. In fact, his copy of Rousseau’s Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men shows how, at the end of some paragraphs, he wrote such comments as “I believe nothing of all that”.

He could be just as critical about Voltaire. Nor was he a huge fan of John Milton. Later in life, he would approach an Englishman reading Paradise Lost and let him know that the “British Homer lacks taste, harmony, warmth and naturalness”.

Napoleon had an even more dismal view of his younger brother Lucien Bonaparte’s 20,000-verse epic poem about Charlemagne, which he regarded as a waste of time (both for writer and reader). And he had no use whatsoever for the 18th-century French novelist Claude Prosper Jolyot de Crébillon.

A 1997 article written for the Guardian by Paul Webster related how Napoleon would also try contemporary novels, often reading them while riding in his carriage. If such books failed to sustain his interest, he would simply throw them out the carriage window.

One book that he never flung out the window was Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1774 epistolary novel The Sorrows of Young Werther – a work that, upon its initial publication, had led many young male readers to imitate Werther’s clothing style and, reportedly, also led some to imitate his suicide as well. This was perhaps Napoleon’s favourite work of fiction, though he also held in high regard the writings of English author Henry Fielding.

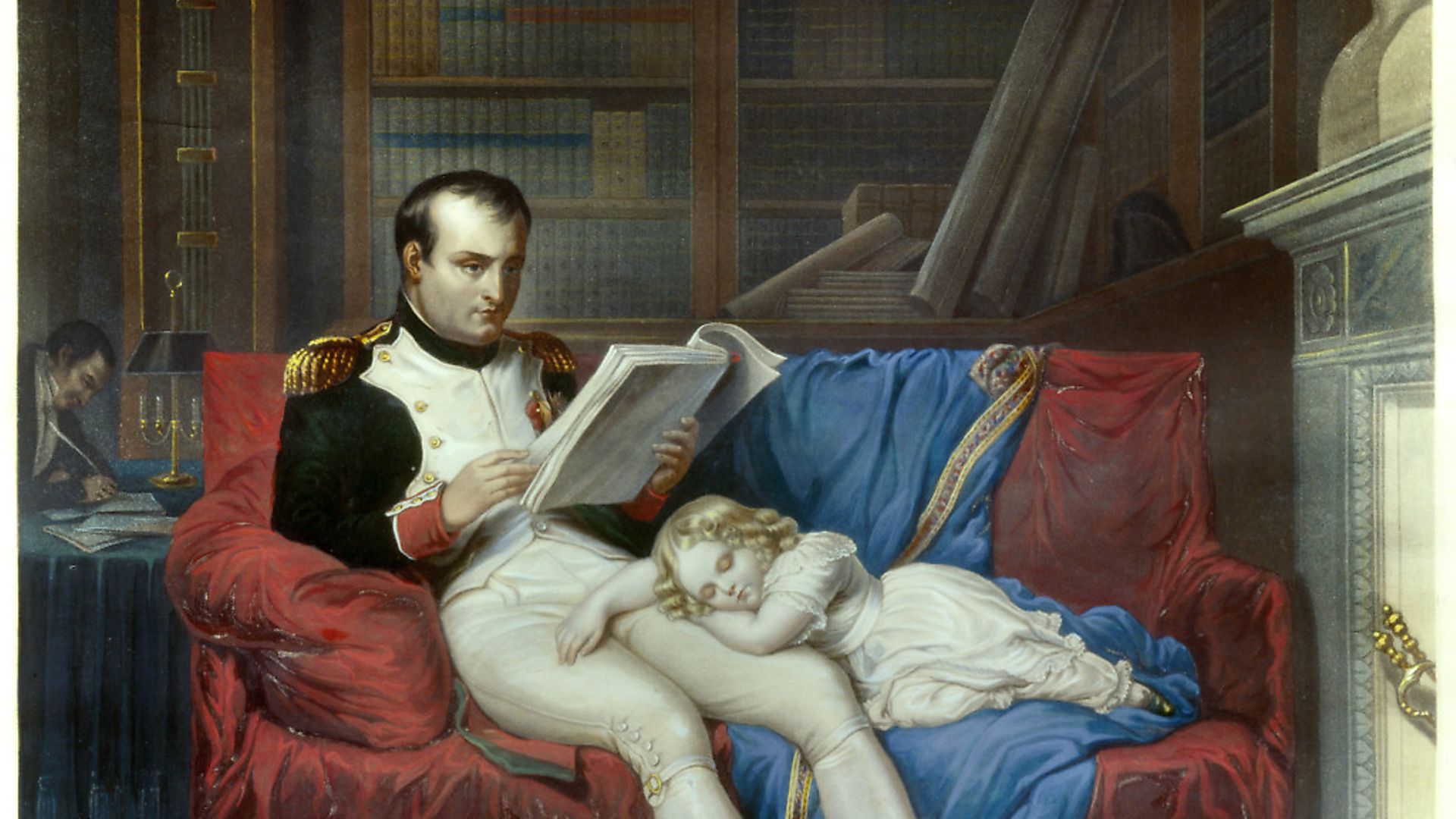

Indeed, the demands of his military career often took first priority, but Napoleon (who was a general by his mid-20s) could not separate himself from books for long. Eventually, he made sure that any empire-building journeys were accompanied by a portable library curated by a personal librarian.

When he left France on a quest to take control of Egypt, Napoleon’s portable library contained about 320 volumes, more than half of them historical, according to the 1865 book Libraries and Founders of Libraries.

For someone who was then making such impact on the present, the soon-to-be-emperor’s tastes were largely stuck in the long ago past – ancient historians such as Justin, Plutarch, Polybius and Thucydides, along with such poets as Homer, Virgil, and the comparatively modern Renaissance-era Italian bard Ludovico Ariosto.

On his way back to France from Egypt, Napoleon decided to leave part of his library in Marseilles. A 1906 article in the San Francisco Call newspaper tells of the recent discovery in Marseilles of 19 books he had deposited. Among other titles, there were two volumes of Francis Bacon’s Essays, Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s Les songes et visions philosophiques, and Madame de Staël’s Treatise on the Influence of the Passions.

By the time of this discovery, the French were already well aware that the former emperor was a fan of Machiavelli’s The Prince. In fact, facsimiles of Napoleon’s personal copy – along with the extensive notes he took in the book’s margins – saw more printed editions in France than non-annotated Machiavelli works.

Though Napoleon would sometimes opt for political philosophy, the two genres which most often satisfied his near-lifelong bookish cravings were history and drama.

Regarding this latter genre, he was particularly drawn to the 17th-century French dramatists Jean Racine, Jean-Baptiste Poquelin (better known as Molière) and Pierre Corneille. In fact, his admiration of Corneille was such that he once remarked on how, if the playwright were still alive, he “would have made him a prince”.

Though Molière plays were frequently comic, if not farcical, Corneille and Racine were largely tragedians. Napoleon especially appreciated tragic dramas that glorified the virtues of courage and honour, as related Ira Grossman on the website napoleon-series.org. When he was younger, Napoleon wanted his tragedies to culminate in bloodshed, but as he aged his aesthetic senses matured and he preferred a more subtle climax.

No amount of refined taste, however, could spare him the events at Waterloo. But although this terminal defeat impacted his life and legacy, it did not damper his love of reading. In fact, his ensuing exile on the island of Saint Helena in the remote South Atlantic was highly congenial to his bookish pursuits. And, to their credit, those in charge of his exile were thoughtful enough to let the deposed emperor bring a sizable library.

Forever confined on his faraway island, Napoleon often read aloud to himself, especially in the evenings. Long into the night, he devoured books on Egyptian history. And he also evinced a special liking for the African travel accounts of Scottish explorer Mungo Park.

One book with which he had a more complicated relationship was the Bible. Raised as a Catholic, he had been a deist throughout his adulthood, before reconciling with the Church shortly before his May 5, 1821, death at age 51. For the last six years of his life, the exiled Napoleon – deprived of his warpath – had been able to fully indulge his inner bookworm.