CALDER WALTON on how Brexit could spell the end of Britain’s advantage in espionage.

From John le Carré’s novels to the insatiable popular interest in James Bond, Britain has long enjoyed, and cultivated, an image of producing superior spies. This reputation is based on more than myth. For decades during and following the Second World War, the painstaking real-world work of British intelligence officers was one of the United Kingdom’s primary sources of power.

That power, and its underlying foundations, is now in jeopardy thanks to Brexit, which will have a cascading series of repercussions for British intelligence: It will shut Britain out of European Union institutions that have benefited British national security, and it may also jeopardise the special intelligence relationship with the United States, which may look to deepen relations with Brussels instead. But while Brexit may now be inevitable, there are still ways for the UK to avoid this outcome.

Britain’s intelligence services – MI5, which handles domestic security intelligence; MI6, which does foreign intelligence; and GCHQ, which focuses on signals intelligence (SIGINT) – have been touted at home and abroad as the Rolls-Royces of intelligence services. But they weren’t always.

Declassified records show that, prior to the Second World War, British spy agencies were often more like rickety cars than luxury vehicles. MI5 and MI6 were established in 1909, and at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, both services had scant resources: MI5’s staff totalled 17, which included its office caretaker.

The situation had scarcely improved by the start of the Second World War in 1939. A declassified in-house MI5 history shows that on the eve of the war, the agency’s counterespionage section had just two officers – with responsibilities for the entire British empire. MI5 and MI6 did not even know the name of the German military intelligence service, the Abwehr.

Of course, British intelligence went on to notch up unprecedented successes against the Axis. These victories were largely owed to achievements at Bletchley Park, where British and Allied code-breakers cracked Germany’s notorious Enigma cipher machine, giving them greater intelligence about the Third Reich than almost any state has enjoyed about another government in history. (Some historians have suggested that British SIGINT collected at Bletchley Park may have shortened the Second World War by two years.)

That success carried over into the post-war period, when Britain’s intelligence services helped London punch far above its weight – even as its hard power declined. In part, this was due to the British government’s successful management of international perceptions of its abilities. Whitehall cultivated an image of pre-eminent intelligence acumen by selectively releasing secrets about Bletchley Park and other astonishing wartime successes, such as MI5’s ‘double-cross system’, through which it managed to capture German spies in Britain and turn many of them into double agents. As Sir J.C. Masterman, the head of the double-cross system, succinctly put it: British intelligence “actively ran and controlled the German espionage system in this country”.

During the Cold War, British spooks managed to further burnish their reputation. GCHQ’s technical capabilities were first-rate, and Britain’s overseas territories proved useful for collecting SIGINT for the UK and the United States. Britain also pulled off some spectacular espionage and counterintelligence coups.

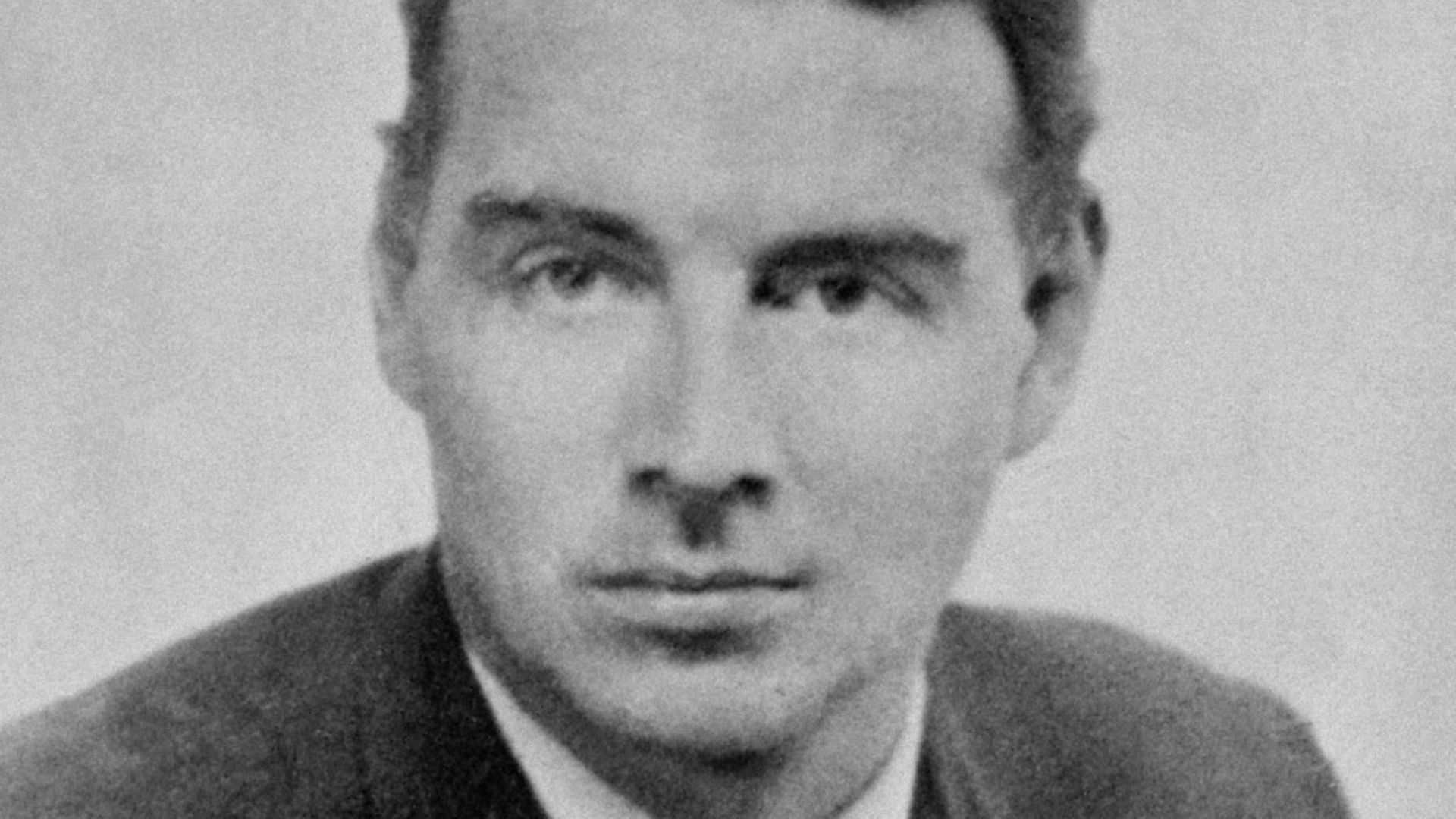

During the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, when the world came closer to nuclear Armageddon than at any other point in history, information provided by Oleg Penkovsky – who was positioned deep inside Russian military intelligence and worked for both MI6 and the CIA – gave Washington crucial insights into the status of Soviet missiles in Cuba. Penkovsky’s intelligence, codenamed Ironbark, revealed, among other matters, how far Soviet missiles were from being operational and thus how much time Washington could spend diplomatically fencing with Moscow.

Some years later, MI6 managed to recruit a senior KGB officer, Oleg Gordievsky, who became rezident (head of station) in London and secretly provided Britain and the United States with unique insights into the Soviet Union’s intentions and capabilities.

Such feats turned intelligence into a force multiplier for Britain during the Cold War, helping it retain a seat at the high table of international affairs despite its declining economic and military power. GCHQ worked so closely with the US National Security Agency (NSA) that they essentially functioned as two sides of the same massive, trans-Atlantic, SIGINT collection machine. This interagency relationship gave London political leverage in Washington.

Records at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library, for example, show instances of British intelligence officials being given access to Washington’s most senior policymakers, including Henry Kissinger, and even attending and briefing National Security Council meetings, in ways unimaginable for officials of any other countries.

Files declassified nearly 20 years ago show that in the 1960s, Britain’s highest intelligence assessment body, the Joint Intelligence Committee, advised successive prime ministers that joining Europe was essential to Britain’s strategic future: Doing so was the only way the country could escape its economic doldrums and safeguard its special relationship with Washington, which viewed the UK as more valuable within Europe than without. According to records at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, the United States saw London as a like-minded, trusted ally, one that literally spoke the same language and that could exert influence over Europe’s more troublesome members.

After joining in 1973, Britain also gained a say in major European decisions – which proved useful for the United States in matters including military strategy and trade.

If the UK now leaves the EU, there are good reasons to suppose that Washington will come to view London as less strategically important. US officials are likely to start asking whether the United States really needs Britain anymore or whether it would be better off strengthening its intelligence relations with the EU.

Supporters of Brexit correctly point out that after joining Europe, Britain’s intelligence agencies have continued working with EU members on a bilateral basis, not with the EU as a whole – so leaving the union shouldn’t make any difference. But that optimistic view discounts the real impact Brexit will have on British national security. The UK has benefited from membership in EU bodies such as Europol and the Schengen Information System, which provide it with information on terrorism, human trafficking, and other serious crimes.

The British police and MI5 used such data to track down the Russian officers who tried to assassinate a former Russian spy, Sergei Skripal, in Salisbury in 2018.

If the UK leaves the EU, however, Britain would lose access to such information – one reason that prior to the 2016 Brexit referendum, former British intelligence heads publicly warned that quitting the union would damage the country’s security. Since then, the messy exit process has only heightened their concerns because it’s increasingly doubtful that Britain, amid the present diplomatic rancour, will be able to salvage comparative alternative arrangements with the EU.

Following Brexit, the intelligence services will have to adapt. One area offers the most promise: the cyber-realm. GCHQ is already a world leader in digital intelligence. Edward Snowden’s unauthorised disclosures in 2013 showed how closely GCHQ works with the NSA, exploiting internet platforms to collect intelligence.

Although its role was largely overlooked, GCHQ was apparently the first to identify and warn US intelligence about a Russian hacking group, Fancy Bear, which broke into US Democratic National Committee emails in 2016.

Britain would be wise to double down on its comparative advantage in digital technologies; indeed, it seems to already be doing so. GCHQ and Britain’s new National Cyber Security Centre have been undertaking recruitment and training drives for cyber-expertise, as has MI6.

The latter indicates that old-fashioned human espionage – MI6’s territory – will be important even in the new digital realm: Recruiting well-placed agents inside foreign cybergroups will be a key way to unlock their secrets.

Britain’s National Cyber Security Strategy for 2016-2021 publicly acknowledged for the first time that the country has offensive hacking capabilities. A likely future area of growth for British intelligence will be to enhance these capabilities and carry out cyberattacks on state and non-state threats, like Israel and America’s alleged Stuxnet virus attack, uncovered in 2010, targeting Iran’s nuclear programme.

History shows that Britain’s spies are extraordinarily good at turning dismal disadvantages, as they had at the start of the Second World War, into staggering successes. Cyberwarfare offers that opportunity again – especially since it doesn’t require conventional military power, which has been difficult for Britain to pay for in its prolonged era of austerity.

Another area of future growth for British intelligence will likely be covert action with a focus on defending against disinformation. A major challenge facing Western societies is the insidious growth of fake news promulgated online by authoritarian regimes such as China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. Most countries still lack a strategy for dealing with such disinformation; Britain, however, has a useful model in its recent past.

During the Cold War, the country’s shadowy anti-Soviet propaganda unit, the Information Research Department, provided fact-based, rapid, and lucid responses to KGB forgeries. It provides a template for dealing with disinformation today; Britain would be wise to update the approach for the social media era.

Britain’s intelligence services could also start spying on the EU. No one on the outside knows how much of this, if any, the UK already does; so far, the records, if they exist, have yet to be declassified. But Britain has a long history of spying on its allies: British code-breakers intercepted and read US communications before America entered both the First and Second World Wars.

In recent decades, the extraordinary and wide-reaching political cooperation that EU membership necessarily entailed probably made British spying on Europe too risky – and vice versa. Once it departs the EU, however, Britain would be free of such constraints. Indeed, since Brexit talks began, rumours have suggested that British intelligence has been targeting EU negotiators. Whether or not that’s true, it seems unlikely that following Brexit, both sides will descend into mutual feeding frenzies of espionage.

Common external threats, especially Russia and China, and the chill of a new cold war, mean that British and EU agencies will have incentive to keep cooperating.

Brexit will force Britain’s intelligence services to answer uncomfortable questions they have not had to confront since the Second World War: What can they offer that others cannot? That Brexit is taking place at the same time as the cyber-revolution, however, offers opportunities for Britain to maintain some semblance of its current global power. Investing in digital intelligence offers London the best – and perhaps only – way out of the strategic intelligence quagmire Brexit has placed it in.

Calder Walton holds a doctorate in history from Cambridge and is the author of Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, the Cold War, and the Twilight of Empire, published by The Overlook Press