In 1972 Ziggy played guitar, Marc Bolan hit his stride and blokes across Britain made nervous moves towards their sister’s make-up bag. Here SOPHIA DEBOICK rediscovers glam Britannia

The events of the year were notoriously dreadful. On January 20, the Commons sitting was briefly suspended when the announcement that unemployment stood at 1,023,583 – topping one million for the first time since the 1930s – resulted in outraged jeering of PM Edward Heath. Northern Ireland was descending into complete crisis. Hundreds of suspected IRA members had been interned without trial the previous summer and 13 unarmed protestors, most of them teenagers, were shot and killed by British soldiers in Derry at the end of January in what came to be known as Bloody Sunday. 1972 would be the bloodiest year of the Troubles, with 497 killed. On the mainland, a seven-week miners’ strike from early January saw the lights go out. This was followed by a dockers’ strike in July and a state of emergency being declared for the second time that year as a result of industrial action.

When Idi Amin gave the 57,000 Asian Ugandans with British passports 90 days to leave the country in August it fomented existing racial tensions in the UK, and the arrival of this community would go on to change the face of British society. In September, eleven members of the Israeli Olympic team were kidnapped and killed by Palestinian terrorists at the summer games in Munich as the world watched.

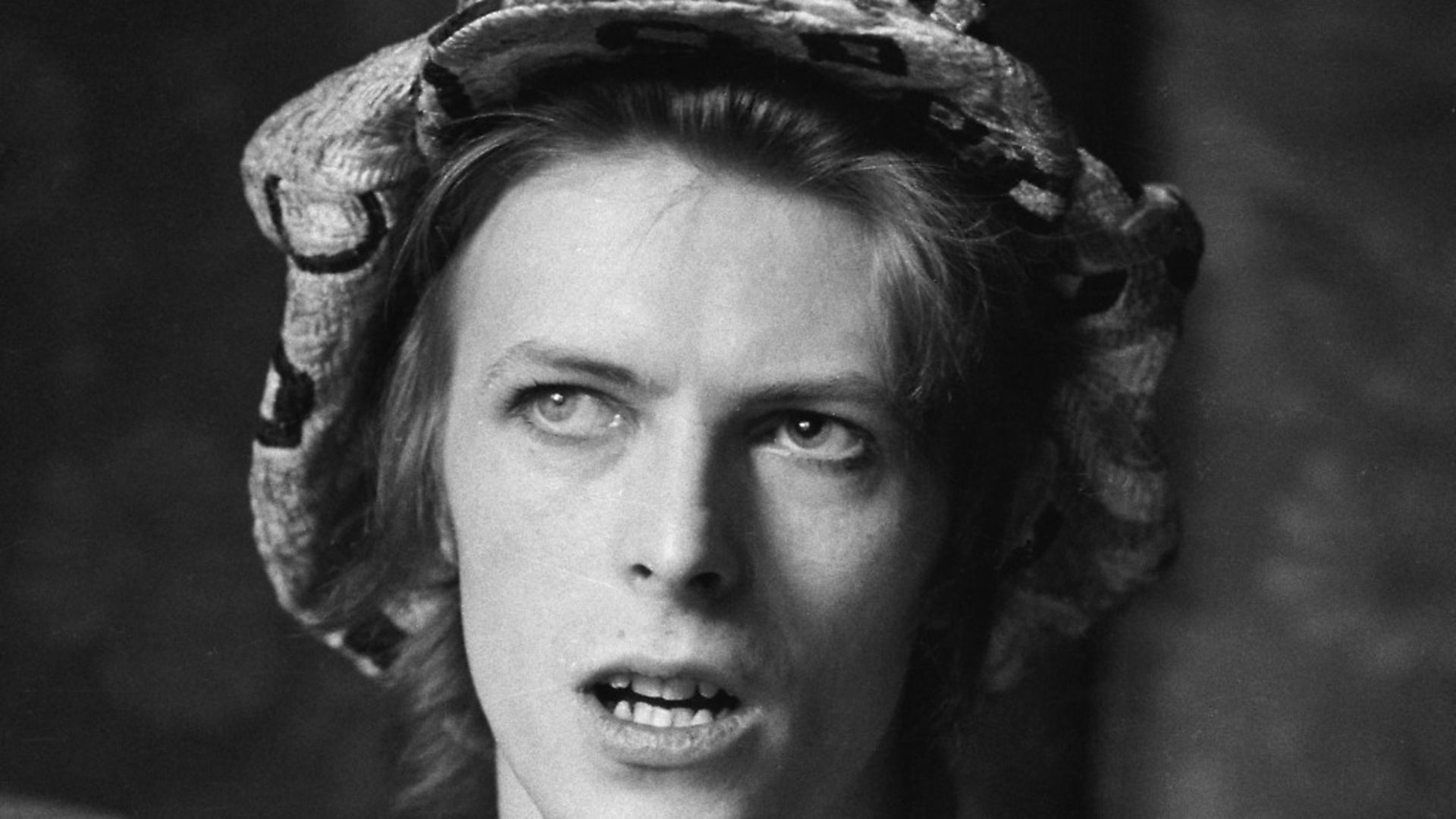

Violence was also the theme when Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange hit UK cinemas in January. While it caused a moral panic, for former mod David Bowie it was the protagonists’ sartorial fastidiousness that was of interest, and he quickly ditched his long-haired bohemian look, seen on the sleeve of December’s Hunky Dory, and adopted a short, choppy hairdo, a quilted jumpsuit and laced boxing boots, inspired by the film’s Droog gang. That same month, ever with an eye to a PR opportunity, he announced in an interview with Melody Maker ‘I’m gay’.

On February 8, having just finished recording The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, he appeared on The Old Grey Whistle Test alongside his northern backing band of Mick Ronson, Trevor Bolder and Woody Woodmansey. Both his material and his electric charisma had a clear ability to shock. The Velvet Underground-inspired Queen Bitch, apparently taking New York transvestites as its theme, announced this was a band with rare underground influences, and Bowie gave a savage emphasis to the reference to ‘a queer’ on the apocalyptic Five Years. If the boringly grown-up Whistle Test hadn’t been broadcast at gone 11 on a Tuesday night this might have been the point that Bowie burst into the national consciousness, but he had to wait five months for that moment.

Following the June release of the Ziggy Stardust album, Bowie performed Starman on Top of the Pops on Thursday July 6, 1972, a few minutes of television that has, rather hyperbolically, come to be seen as the point of origin for anything transgressive in British music that followed. In a similar get-up to the Whistle Test performance but now with gravity-defying red hair and ethereally snow-white skin, Bowie pointed at the camera and sang ‘I had to phone someone so I picked on you-hoo-hoo’, making every awkward adolescent watching feel it was them he was singling out, if later analyses are to be believed. The weirdos were more numerous than they thought however, as the performance propelled the single to number 10. Two days later, at a gig at the Royal Festival Hall, Bowie introduced himself not as ‘David Bowie’ but as ‘Ziggy’. The persona was complete, as performer and character merged.

Bowie had succeeded in becoming the ultimate pop star by mid-1972, but the second half of the year would see him take on a behind-the-scenes role as a record producer who could work miracles, turning around the careers of his own idols. Lou Reed and Iggy Pop had represented a seedy transgressiveness absent from British rock which Bowie had managed to aestheticise into the subtext of his more saleable songs. Starman had proven he knew how to combine hit-making with credibility and it was this talent he offered to Reed. In August, Bowie and Ronson, the more junior musicians who nonetheless proved themselves seasoned professionals, produced Reed’s Transformer at Soho’s Trident Studios. This future classic spawned the hit Walk on the Wild Side and revived Reed’s career after a debut solo album that had badly flopped. That autumn Iggy Pop, heroin addicted and in disarray, signed to the same management company as Bowie at his instigation and moved to London, where he recorded Raw Power. With Iggy mixing and producing the album himself the result was a mess and Bowie remixed it while on tour in the US in October, although to little better effect (Iggy’s use of just three tracks of 24 gave him little to work with). Yet the album would become a proto-punk staple and it marked the beginning of a friendship which lasted decades, the two men becoming flatmates and achieving critical acclaim in the second half of the 1970s and going on to commercial success in the 1980s.

Bowie had reached out to teenage misfits, and the raising of the school leaving age to 16 from September 1972 suggested that this was perhaps the second age of the teenager. Glam certainly had a decidedly young edge. Alice Cooper’s School’s Out hit the top of the charts in August, the Bowie-penned All the Young Dudes by Mott the Hoople was number 3 at the beginning of September and that same month T. Rex saw their anthem Children of the Revolution only kept off the top spot by Slade’s Mama Weer All Crazee Now and then David Cassidy’s soppy How Can I Be Sure? But there was also a backward-looking, nostalgic strain to glam.

Gary Glitter’s debut Rock and Roll Parts 1 and 2 was an ode to 1950s Americana, even if one-time Beatles collaborator Mike Leander’s minimalist production, the instrumental remix B side and Glitter’s manic stage presence were something quite new and would be influential, before Glitter’s child abuse convictions resulted in his erasure from pop history. Elton John was only obliquely glam, by way of sequins and a modishly sci-fi reference to a ‘rocket man’ but 1972’s Crocodile Rock was also part of this rock ‘n’ roll revival theme.

The high-concept art rock of Roxy Music was something more sophisticated, but their look also flirted with 1950s retro chic. While Marc Bolan had anticipated Bryan Ferry’s glittery eye make-up when the band appeared on Top of the Pops in August, T. Rex were always understandable as long-haired former hippies. Ferry, however, could not be easily categorised, with his sharply-cut sequined jacket and Teddy Boy hair. Every member of the band looked freakish, but none more so than Brian Eno, with a bone structure straight out of Doctor Who and an early synthesiser instead of a recognisable instrument.

Glam was far from the only game in town in 1972. Hard rock and prog was going strong, with the release of Deep Purple’s number one album Machine Head, Black Sabbath’s Vol. 4., Hawkwind’s Silver Machine and Yes’ career-defining Close to the Edge.

In January Pink Floyd performed Dark Side of the Moon live in its entirety, although the album wouldn’t be released until the following year. A piece in the NME in December used the phrase ‘Krautrock’ for the first time, in a series looking at such arch-influencers as Can, Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk. The singles charts were a mixed bag, and even with John, I’m Only Dancing reaching number 12 in October, Bowie didn’t trouble the top 100 best-selling singles. Instead Little Jimmy and Donny Osmond, The New Seekers, Chicory Tip, Harry Nilsson, Rod Stewart, Don McLean and Gilbert O’Sullivan were all chart-toppers. Amazing Grace by the Band of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards was the biggest-selling single of the year.

While much has been written about glam heralding social change, Ziggy Stardust’s interplanetary origins symbolising the complete malleability of identity beyond the confining labels of sex, race and class, the reality was very different, and it’s notable that for all their alleged androgyny, the leading lights of glam were mostly heterosexual white men who ‘transgressed’ from a position of unassailable privilege. While the weekend before the famed Starman performance, when Bowie had provocatively dangled a bangled arm around Mick Ronson’s shoulders, had seen the first official gay pride march take place in London, and it seemed like a sexual revolution was afoot, this was still an era characterised by entrenched illiberalism.

The late hippy values of Jesus Christ Superstar may have debuted in the West End that August and Bob Fosse’s Cabaret embodied much of the decadent spirit of glam, but racism, misogyny and homophobia riddled other areas of popular culture. 1972 was the year Love Thy Neighbour and Are You Being Served? debuted on British TV. National Front membership was growing, polling showed widespread hostility to gay people, many of whom remained closeted, and the Sex Discrimination Act was three years away. Not for nothing was Spare Rib founded that summer, setting itself the task of exposing gender inequality to a mass market audience.

Bowie pushed Ziggy to the sartorial limits as 1972 progressed, before killing him off in July 1973 on the concluding date of 18 months of touring. He had adopted Japanese kabuki costumes and face paint to match in the intervening months and his physical appearance on Top of the Pops in January 1973 would be more other-worldly than ever; gaunt, with eyebrows shaved off and hair now flaming red.

In June that year the BBC’s Nationwide would brand Bowie ‘a bizarre self-constructed freak’ and wring its hands that ‘It is a sign of our times that a man with a painted face and carefully adjusted lipstick should inspire admiration from an audience of girls aged between 14 and 20’. With Bowie moving on, glam would get taken over by the cartoonish end of its spectrum. Hit-makers Nicky Chinn and Mike Chapman kept Bowie’s The Jean Genie off the top with The Sweet’s remarkably similar and undeniably brilliant Blockbuster! in early 1973. The Glitter Band, Alvin Stardust, Showaddywaddy and Mud (another Chinn and Chapman act), saw the rock ‘n’ roll revival turn of glam take over and the retrospective popular image of the genre has become as ossified as the rhinestones that adorned its propagators’ stage costumes. But in 1972, glam was still as unpredictable as the times that spawned it.

Dr Sophia L Deboick is a historian of popular culture. Follow her @SophiaDeboick