Despite the divisions wrought by Brexit, there is still a middle ground left in the UK. Unfortunately, our political system is not designed to cope with compromise, says historian GLEN O’HARA.

For nearly a hundred years, British politics has been acted out as a drama of red versus blue. Our public life revolved around the poles of class and redistribution: poorer against richer, redistribution versus rewards, concert as opposed to competition. But there are now some signs that all this might be changing under the pressure of the Brexit crisis.

There’s lots of survey data that tells us people are beginning to think of themselves as Leave and Remain, rather than Conservative and Labour – brands that have been in decline for decades in any case, which are riddled with internal contradictions, and were ripe for obsolescence.

First and foremost, Britain has become incredibly divided, not just on the question of Brexit itself, but on how to deal with the whole chaotic process. YouGov numbers show that 72% of Remainers back the idea of a cross-party government that would delay Brexit long enough to hold an election: 76% of Leavers oppose the idea. Ipsos-Mori’s last survey showed the two tribes interpret every twist and turn in the drama very differently. Some 74% of Remainers thought that Boris Johnson’s suspension of parliament was the wrong thing to do; only 20% of Leavers agreed with them.

Second and even more importantly, Britons seem to be developing a much stronger emotional attachment to their ‘side’ of Brexit than they have to political parties. Recent work by polling guru Sir John Curtice has demonstrated this beyond doubt: 44% of respondents say that they feel a ‘very strong’ attachment to Leave or Remain: only 9% can say the same about a political party. Even the figures for ‘fairly strong’ attachment see Brexit allegiance beat party identity by 33% to 28%.

This sense of deep schism shows up in apparently less relevant cultural markers too, in data that also suggests that the radicalisation is asymmetric – that is, Remainers can be more partisan and energised than Leavers. Boris Johnson and Michael Gove have achieved what the EU never could: they have created a pro-European culture in Britain.

Take the idea of your children marrying someone from the opposite Brexit camp. A recent YouGov survey showed that 39% of Remainers would be very or somewhat upset if their child married a Leaver. That’s more than the number of Labour voters feeling the same if their offspring took up with a Tory (34%). Only 11% of Leave voters felt the same about a child marrying a Remainer, though that’s still about the same number as to the 13% of Conservatives who would feel the same about their child marrying someone from the red team.

It’s important not to exaggerate here. Most Britons are not at each other’s throats about Brexit. In fact, lots of them would quite like the whole thing to go away. There’s a lot of latent potential for at least a measure of consensus around a ‘soft’ Brexit that would see Britain leave the EU, but not move all that far away.

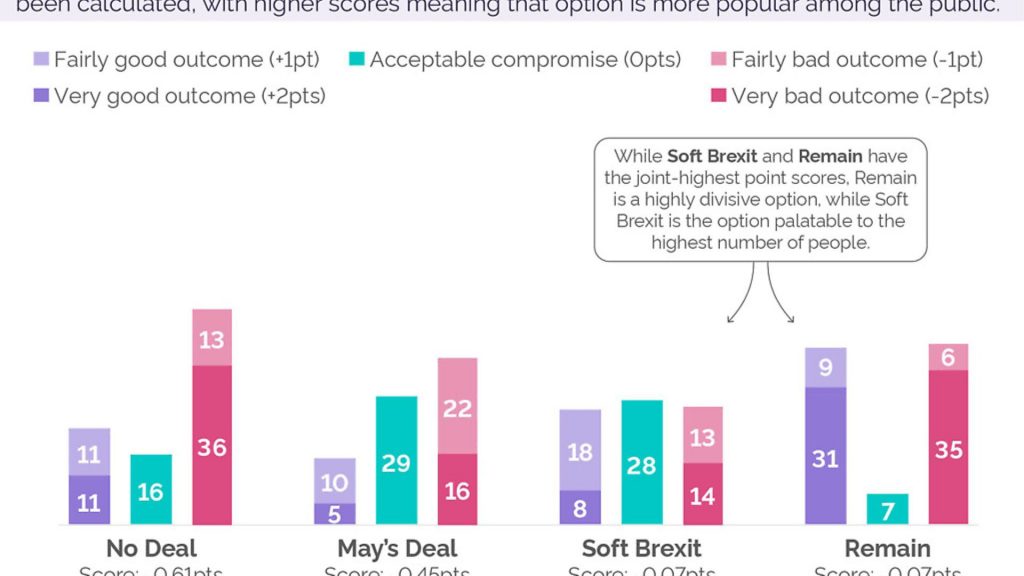

When pollsters ask voters what they might accept, rather than what they ideally want, a rather more nuanced picture emerges. One study by Professor Will Jennings of the University of Southampton has shown that 54% of voters think that a soft Brexit – in which the UK stays inside the EU customs union and single market – either a very or fairly good outcome, or an ‘acceptable compromise’. Some 47% think the same of Remain, but only 38% say the same about a no-deal exit.

Earlier work by Professor Christina Pagel of UCL has similarly shown how different voting mechanisms could be used to get to a final and single answer among all the options available. It is true that allowing voters to choose in an Alternative Vote ballot, listing their preferences from first to last, would probably see Remain beat no-deal; but asking them to choose between every pair of options, and picking the one that beats all the others, would again end up with a soft Brexit victory.

The problem we face as a country is that a multi-choice referendum – or some other deliberative mechanism, such as constant parliamentary votes to finally settle on a ‘least worst’ solution – seem very unlikely. Our first past the post voting system, and traditions of majority government under a strong executive, militate against any kind of change that might help us talk and heal. So Brexit will go on pushing open the fault lines in our divided parties, picking at the wounds in a political system that just can’t cope with a country divided on these lines.

The short- to medium-term future looks like those long-running crises that have fixated Westminster and Whitehall before: over free trade in the 1840s, Irish Home Rule in the 1880s and 1890s, tariffs and trade in the 1900s. Those pitched battles weren’t solved quickly either.

Labour and the Conservatives have fought it out for generations. We’ve got used to the map being coloured in red and blue. But we might just have to start thinking about Britain as a country of purple against gold, Leave against Remain, Middle England and Middle Wales against the cities and Scotland.

That will scramble loyalties, topple governments, depose leaders – and quite likely leave us mired in the Brexit crisis for quite some time to come.

Glen O’Hara is professor of modern and contemporary history at Oxford Brookes University. He is the author of a string of books and articles about modern Britain. His most recent book is The Politics of Water in Post-War Britain (2017).