As a concept, surrealism’s roots run deep in Britain, even if as an artform it never took hold to the same extent as elsewhere. Yet RICHARD HOLLEDGE reminds us that the country still has a healthy heritage of the absurd.

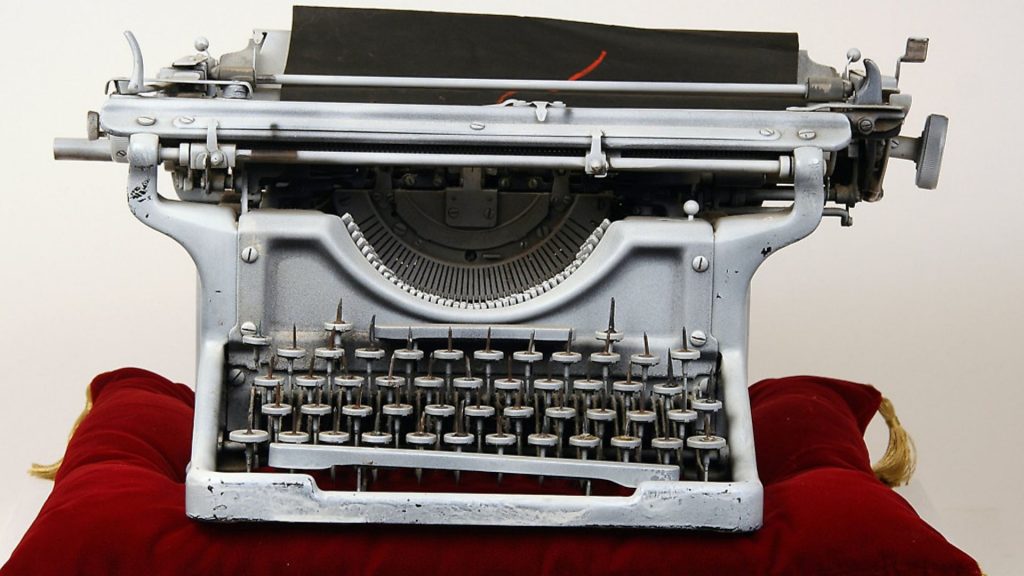

Salvador Dali once turned up for a speech driving a Roll Royce full of cauliflowers, so it scarcely raises an eyebrow to discover he attended a meeting of surrealists wearing a deep sea diving suit, complete with round glass helmet and brass screws.

The event was the International Surrealist Exhibition which opened in London in June 1936. It was a sensation. Few people – even the critics – had been exposed to such irrational images before.

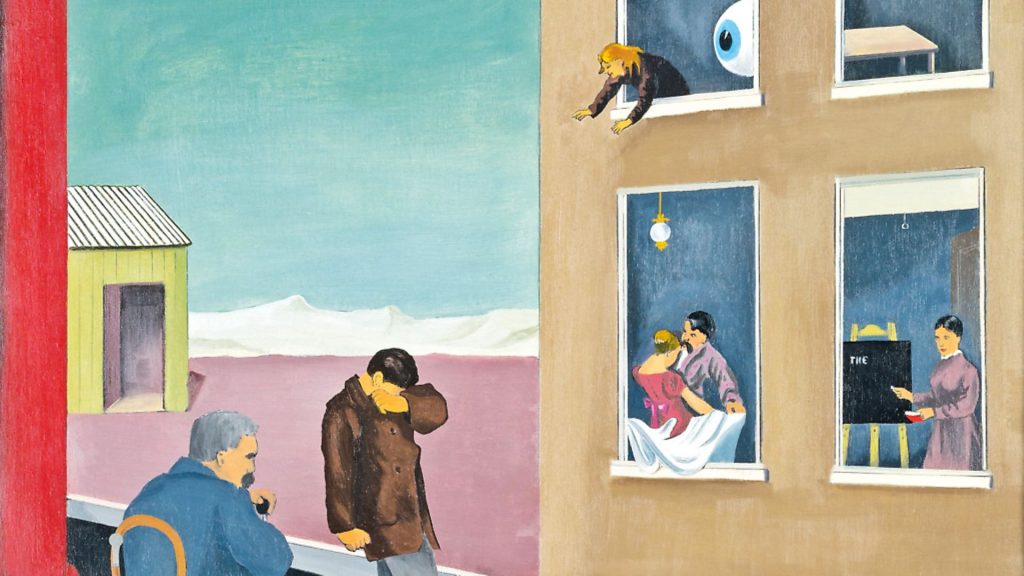

What to make of the grotesque figures in Little Boys Don’t tell Lies (1936) by Reuben Mednikoff (1906-1972)? One figure has a single eye and is vomiting out what looks like a lizard, the conjoined partner sports ferocious fangs and one elephantine leg with seven toes.

But that was the point. Why attempt to define something so illogical? British Surrealists at the Dulwich Picture Gallery decided to present 70 pictures by 40 artists and invited the viewers to make up their own minds about the strange, invariably baffling, juxtapositions of imagery and flights of fancy.

Of course, the gallery is now closed, but it is meeting the challenge of helping virtual visitors to appreciate the show with a clever catalogue, which can be bought online and brief audioguides.

Don’t be deterred by the word ‘postponed’ on the exhibition site, click and find an introduction by the curator David Boyd Hancock, profiles of two artists and a brief aural tour of the exhibition.

You will discover that surrealism had been alive and baffling people in France for some 20 years before the London show. The word was first coined by French poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917 and turned into a movement by the iconoclastic writer and poet Andre Breton.

He had served with the French army in the First World War and come into contact with traumatised soldiers at about the same time he had discovered the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud, who explained attitudes to sex and death by delving into dreams and opening the dark corners of the mind.

Breton recorded the stream-of-consciousness accounts of the patients in what was known as automatic writing, and he enthused about the ‘omnipotence of the dream and in the disinterested play of thought’.

Which explains Dali in his deep sea diving suit; it represented his own descent into the subconscious.

Breton was no painter but many European artists embraced his vision. They were generally left-wing or communists and, reeling from the horrors of the war, they feared for the survival of a society now threatened by the rise of fascism.

These fears were shared by many British artists of the time but surrealism as a movement did not reach these shores until the 1936 show, when the artist Roland Penrose and the young painter David Gascoyne enlisted 23 artists to take part, including Paul Nash, Henry Moore and Leonora Carrington.

They were vastly outnumbered by the European contributors who read like a roll call of 20th century greats – Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti as well as René Magritte, Pablo Picasso and Man Ray – but they shared their desire to challenge society’s complacency and were eager to use perverse, weird, if not wonderful, imagery to break down the walls of conservative culture.

In an essay written the same year eminent art historian and critic Herbert Read declared: ‘The surrealist is opposed to current morality because he considers that it is rotten. He can have no respect for a code of ethics that tolerates extremes of poverty and riches; that wastes or deliberately destroys the products of the earth amidst a starving or undernourished people; that preaches a gospel of universal peace and wages aggressive war with all the appendages of horror and destruction which its evil genius can invent.’

Their code of morality, based on ‘liberty and love’ obviously struck a chord with the public because the exhibition attracted 23,000 visitors. But the Times did not share their enthusiasm.

A critic wrote: ‘Having culled the objects from the unconscious the general procedure seems to be to arrange them with careful incoherence and then paint them academically… one is haunted by the irritating experience of the spiritualistic séance…’

The artist John Nash was just as sceptical, dismissing the works as silly and childish created by the types who would pick up a lump of wood on the beach and assert it to be a work of art – which is just what his brother Paul did with a tree trunk and a giant tennis ball in Event on the Downs (1934).

That does not feature in the exhibition but his masterpiece, We Are Making a New World (1918) – which captures the ‘cesspit of blood, nonsense and mud’, as Breton described war – is included, though one could argue whether its unflinching imagery is really a surreal work.

However hard to define, silly even, the British surrealists did produce striking works.

In Blue Baby, Blitz over Britain (1941) by Edward Burra (1905-1976), an enormous bird with glaring eyes and frightening flapping wings swoops over the wreckage of conflict – quite a contrast to his more familiar landscapes and still lifes – while on a smaller scale, but just as disturbing, two drawings by John Banting (1902-1972), The Oracle (1931) and The Abandonment of Madame Triple Nipples (1939), are cruel eviscerations of the human form.

Banting, who died in drunken obscurity, played the role of artistic rebel with some relish. Eileen Agar, who also features in the show, described him as ‘literally, a colourful figure who lived up to everyone’s idea of a surrealist. From time to time he dyed his hair green, or cut off the tops of his shoes to show his painted toe nails – in homage to Magritte of course’.

One characteristic shared by some of the painters was a kind of studied indifference to craft or technique. David Gascoyne (1916-2002) declared: ‘All that is needed to produce a surrealist picture is an unshackled imagination… and a few materials: paper or cardboard, pencil, scissors, paste, and an illustrated magazine, a catalogue or a newspaper. The marvellous is within everyone’s reach.’

One result, a collage of Perseus and Andromeda (1936), set on a sea shore with watchful seals around Perseus who is in a box and Andromeda, whose head is on a tennis racket.

Many of the most arresting images are by women. According to a critic at a show organised by gallerist Peggy Guggenheim in New York in 1943, women excelled at surrealism because the movement was ‘about 70% hysterics, 20% literature, 5% good painting and 5% is just saying ‘boo’ to the innocent public.’

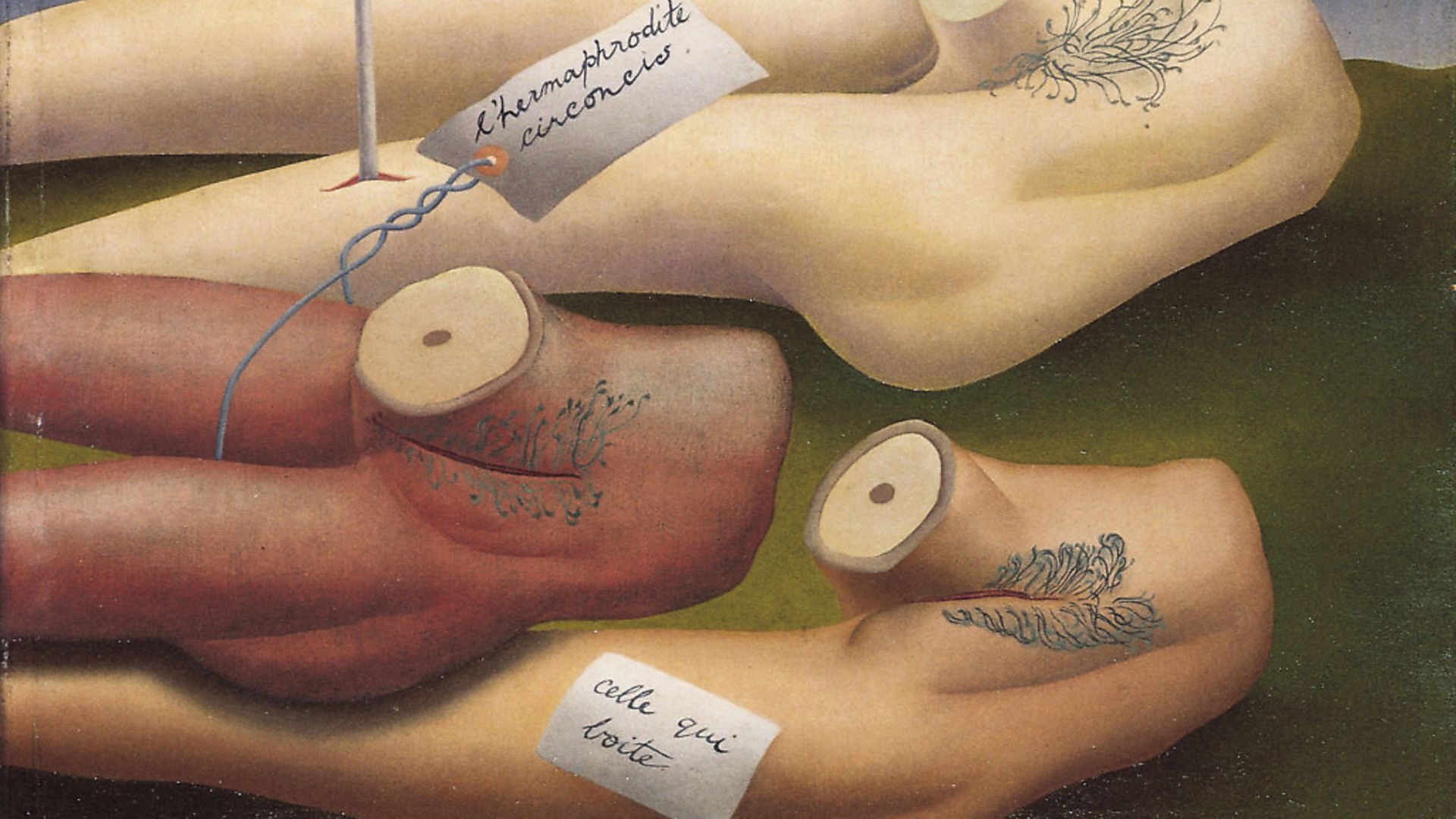

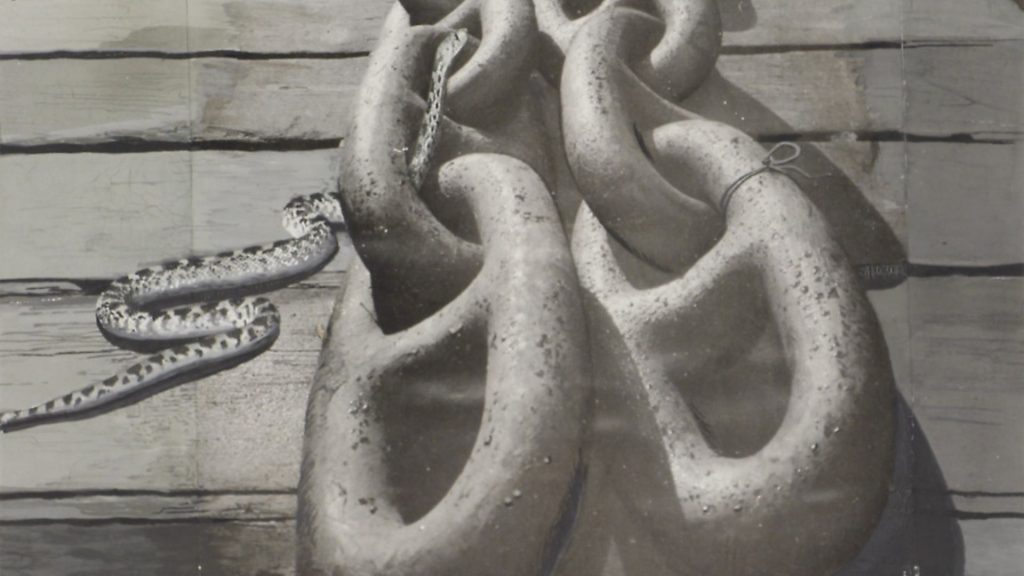

Putting that somewhat misogynistic judgement aside there is a good percentage of all those elements in The Pine Family (1940) by Ithell Colquhoun (1906-1988). It is impossible not to recoil at the clumps of what look like severed limbs attached to puzzling labels such as Atthis, who was a woman mentioned in love poetry by Sappho, which do little to help the viewer’s understanding. But as the gallery audio guide explains, she had an ‘unstoppable imagination’.

Colquhoun also affected an apparent nonchalance to her art: ‘Sometimes I copy nature, sometimes imagination: they are equally useful. My life is uneventful but I sometimes have an interesting dream.’

One can only guess at the dreams which inspired Stark Encounter by Emmy Bridgwater (1906-1999), a bleak pen and ink drawing of a woman being attacked by a razor-beaked bird, while in The Oneiroscopist (1947), Edith Rimmington (1902-1986) portrayed another strange bird-like creature – more a pterodactyl – with ferocious talons, wearing a diving suit. Perhaps in homage to Dali’s stunt 11 years before.

The paintings are not shown chronologically but by themes such as Automatism and the Subconscious or the Impossible and the Absurd but the first exhibit the visitor comes across is Paul Nash’s Opening (1930-31). It serves as reminder that surrealism – the concept rather than the painting – had been part of Britain’s literary tradition for years and is a neat nod to one of those surrealists, William Blake, whose book The Marriage of Heaven and Hell includes the lines: ‘If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite.’

Nash himself wrote: ‘Actually, of course, surrealism, in almost every form is a native of Britain… We have a heritage second to no other country; but it is a heritage too often ignored or neglected, especially in recent years. The constipated negativism of our dismal Mandarins has set up such a neurosis in the often timid minds of English painters and writers that they dare not freely express their true selves, their real selves, their surreal selves.’

Other British ‘ancestors’ to surrealism include Jonathan Swift, Thomas Quincey with Confessions of an Opium Eater and as the Manchester Guardian wrote in 1936: ‘If a Lewis Carroll can create a world of hookah-smoking caterpillars, mimsy borogroves, and gimbling toves, why should not a Max Ernst or a Joan Miró find the equivalent of such a world in paint?’

Surrealism was a relatively shortlived movement even in France despite, or maybe because, of Breton’s fierce didacticism.

He was ruthless in maintaining his rigid rules of what was and was not surreal. A young Lucian Freud was eager to be entered into the 1936 show but was deemed not surreal enough and Breton’s inflexibility prompted Desmond Morris – before he won fame as a zoologist – to damn him as ‘a pompous bore, a ruthless dictator, a confirmed sexist, an extreme homophobe and a devious hypocrite’.

Nonetheless, if the British artists had found a figure like Breton to drive the movement there might have been more talent to match the Europeans.

Few compare to the wry wit of Magritte, the mischievous swirls and blobs of Miró or the shameless showmanship of Dali.

Breton however, would approve of the catalogue. Brisk pen portraits, a concise history of the movement and sections niftily divided by pages, one with overprints of quotes, another with eyes in place of the letter O, and a mirror to reflect the backward writing on the page opposite.

What he would really enjoy is the reproduction, complete with prancing pony, of his quote: ‘I maintain that anyone who still refuses to see for instance a horse galloping on a tomato must be an idiot.’

Says it all, really.