Even without the complications of Brexit, Britain’s economy is in serious peril. But with attention elsewhere, is anyone in power actually listening?

In the year or so since their victory, Brexit cheerleaders have seized on various apparently positive statistics during the past 12 months to claim that the economy is resilient enough to see through the next few years.

Against mounting evidence to the contrary, their desperate aim has been to prove that Project Fear was just that and that things could carry on as before. In recent weeks, though, that ebullient tone has changed, as it moves beyond all doubt that Brexit is already resulting in higher prices, rising inflation and a growing threat to people’s jobs.

Rival capitals including Dublin and Paris are competing to persuade City banks to re-locate all or part of their operations. Already several leading financial institutions have disclosed that they will move some departments into the EU post Brexit, if not before. The property sector is agog with stories about major relocations to Ireland, France and Germany particularly. Bit by bit, British and overseas companies are hedging their bets, creating escape routes, delaying investment decisions or switching them elsewhere.

The realisation that the modern economy is complex, and often intertwined across borders, underpins growing pressure on the Government to adopt some proper strategic thinking. Whether we Brexit or ‘remain’, Britain needs a better road-map.

Industry figures and academic researchers are leading the clamour. ‘The fact is the UK economy has been in trouble for some time, with or without Brexit, and no amount of spin will conceal that fact,’ says one academic with extensive experience of advising ministers. ‘A few senior people in government are appreciating this at last, but whether they can influence colleagues properly is a moot point.’

A new report by the non-aligned Industrial Strategy Commission further underlines the drastic need for a fundamental strategic review of the British economy – with or without Brexit.

‘The weaknesses and challenges affecting the UK economy are significant. The UK’s current and past industrial policies and practices have significant shortcomings, and are not sufficient to address the challenges facing the UK, nor capitalise on future opportunities,’ says the commission, chaired by leading economist Dame Kate Barker, a former member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee. Her body is backed by the Confederation of British Industry and includes key researchers from Manchester and Sheffield universities.

Their interim report – published in July – cites familiar criticisms of the British economy: ‘Poor productivity performance; pronounced regional differences in economic performance; a high degree of centralisation; a low rate of investment; uneven skills distribution; weak trading performance and a weakening diffusion of innovation.’

That critique is echoed by many industry observers who have become increasingly aghast at the apparent unpreparedness of Government ministers, and the uncertainty about what kind of Brexit they want to create, beyond the ‘free trade’ rhetoric and reducing immigration.

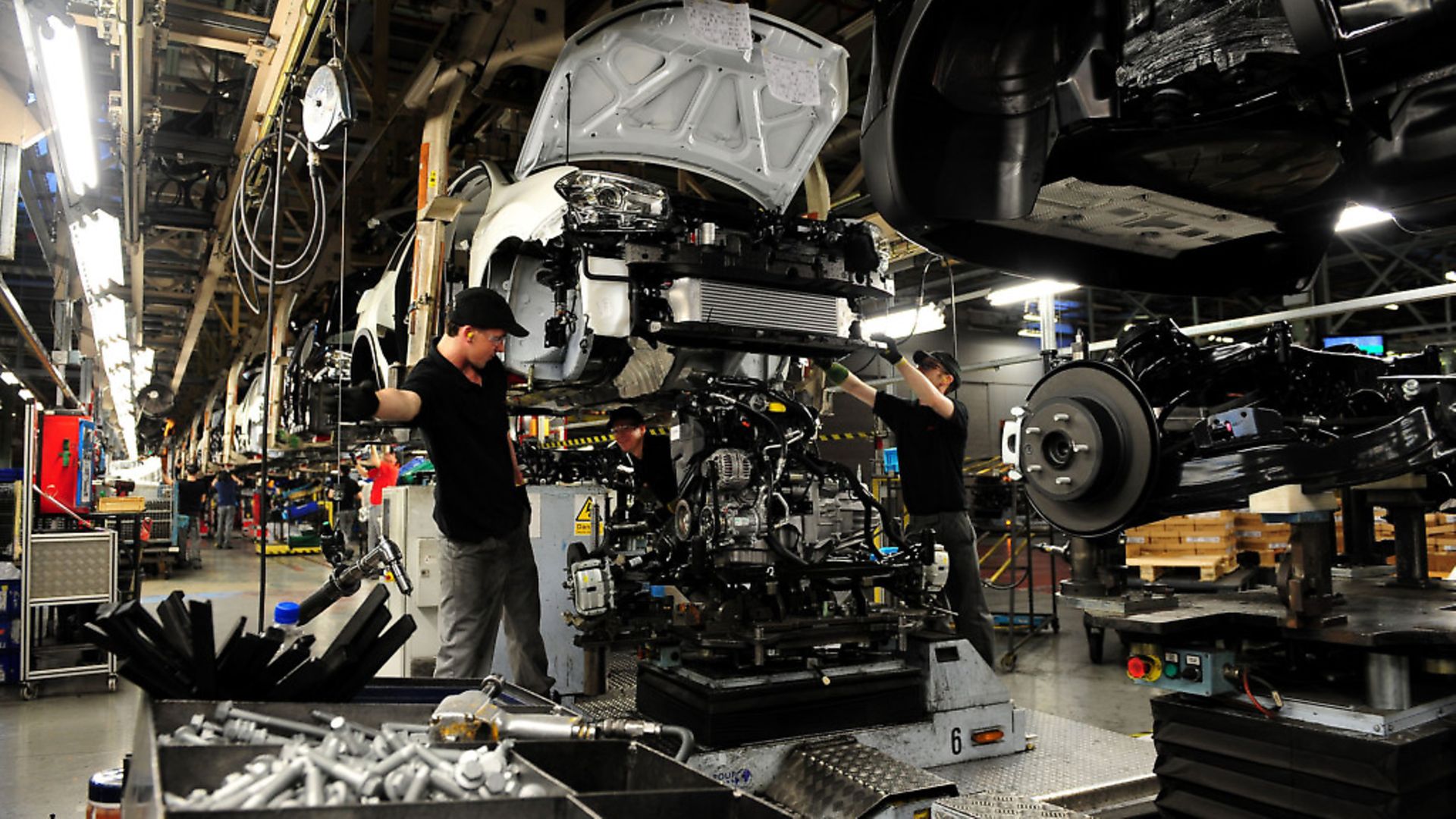

Just in recent weeks, worrying signs have emerged, as major employers take up their positions on Brexit. Toyota has followed fellow Japanese auto giant Nissan by forcing guarantees out of the government, in exchange for new investment; ministers refuse to divulge details of the deals, but they are understood to include what are effectively guarantees that the companies will not lose out in the event of new tariffs being imposed on cars made in the UK. If so, the deals represent blank cheques to be underwritten by the Treasury if Nissan and Toyota are to continue manufacturing in the UK.

At the recent Farnborough International Airshow, the aerospace industry trade body ADS described a Hard Brexit, and particularly one that leaves the UK with no market access deal, as ‘chaos, the worst possible outcome’. The industry, second only to the US and employing more than 100,000 people, is very inter-dependent, not least at Airbus, which manufactures wings in Wales, but everything else on the Continent.

Many employers are concerned that a post-Brexit clamp-down on immigration will affect labour availability and skills levels. The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) reports that investment in car manufacturing during the first half of 2017 was at its lowest level in five years. Companies are biding their time, awaiting the likely outcome of Brexit negotiations before committing to new spending. Total spending this year is expected to be around a quarter of the figure achieved just two years previously – £2.5 billion – and the blame is being laid at the door of Brexit uncertainty. Most of this year’s spend is accounted for by Toyota’s £240 million investment at its Burnaston plant in Derbyshire, made only after the car giant extracted those Government assurances.

The trade body wants at least for the UK to agree an interim deal to remain within the customs union ‘for as long as it takes’ to allow the completion of a comprehensive trade deal between the UK and EU, something that is acknowledged would take many years. Failure to do so would ‘permanently damage’ the industry, according to the SMMT.

The UK car industry made 1.7m vehicles last year, but this year’s figures are believed to be down 10%. Although the industry has been successful in recent years, it is almost completely foreign owned. Vauxhall is being taken over by the French group Peugeot Citroen, Jaguar-Land Rover is Indian, and the other major plants are owned by US, German and Japanese manufacturers. BMW has said that it may start making the electric Mini outside the UK, blaming Brexit uncertainty.

Professor Diane Coyle, of Manchester University’s Institute for Political and Economic Governance, says that the weaknesses in the British economy are not exclusive to manufacturing. Making things – still important in terms of research, technology and exports – accounts for only 20% of the UK economy today. ‘The other 80% is in services. Today even a company that is associated with manufacturing, such as Rolls Royce, makes a great deal of its income from services: after-sales, monitoring, maintenance, for example,’ says Coyle, a leading economic researcher and commentator.

She remains pessimistic about Britain’s chances of securing a beneficial Brexit deal. ‘If we keep talking about ‘trade’ and nothing else, we will be in serious trouble. We do not make goods that lots of countries want. The only good thing about Brexit might be that it makes us focus on key issues facing the British economy, such as the need for investment across the whole country, and not just London and the south-east.

‘We only get a high-productivity economy if we invest in the north of England, the devolved nations, and the south west of England. There are signs that even the Treasury are beginning to understand that now.’

Coyle points out that infrastructure investment decisions are a case in point. Previously the Treasury rules – known as the ‘Green Book’ – measured the case for major investment using current economic measures such as employment or wages. The result was that spending in comparatively wealthy areas – London, for example – could always be justified while rival projects such as the North’s ‘HS3’ high speed rail will look much more risky.

The Brexiteers’ argument that German industry would force its government to do Britain a favour because it sells so many cars here was undermined earlier this month by two major trade bodies, who told the Observer newspaper that the integrity of the EU single market was more important.

There are few encouraging signs on the horizon and with no indication of an early deal in the Brexit talks the ill winds buffeting the British economy continue unabated.

Maurice Smith is a journalist and awardwinning documentary producer. Follow him on Twitter @mauricesmithtvi