Few political autobiographies contain actual revelations. The occasional tit-bit, perhaps, a humorous aside from a foreign dignitary. Which is why the one which comes in the memoirs of Carwyn Jones comes as almost a lightning bolt: that, throughout his final year in office, the former Labour first minister of Wales was battling severe clinical depression.

It followed the suicide of a minister, Carl Sargeant, who Jones had removed from his cabinet amid unspecified allegations of sexual harassment. But, that aside for the moment, it seems a brave move for such a senior politician to spell out the impact on his own mental health so starkly. Jones was prescribed antidepressants.

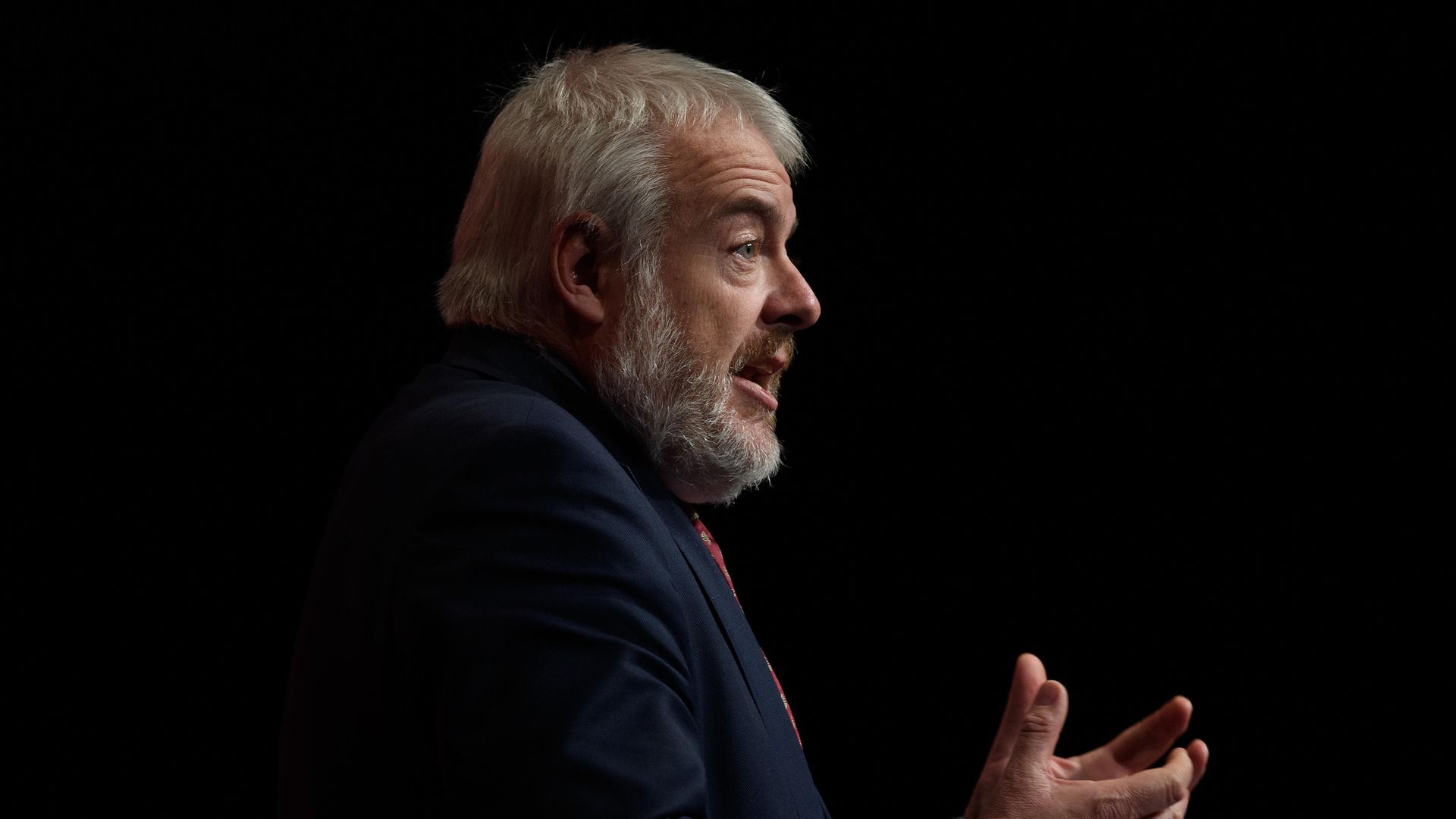

“I decided that it was hugely important that I related what had happened, because otherwise the book wouldn’t have been complete. It would have been a bit of a whitewash in that regard,” the 53-year-old says, via Zoom from his home in Bridgend.

“I also think it’s important for someone like myself to speak out. What I found was there were so many other men who’ve experienced the same thing, or who are experiencing the same thing, who feel isolated. A number of people have contacted me to say ‘thank you for saying this because I don’t feel on my own anymore’.

“Is it a risk? Yes, of course it is, because politicians are meant to be beyond that kind of weakness. But the other thing I wanted to get over is it’s quite possible to function in work and deal with it. It never affected my work or my decision-making or my ability to do the job. It just affected me outside of that context. I was able to compartmentalise what I did.

“And I think it is important for men, men of a certain age – my age – to be able to talk and have someone to talk to rather than keep it all in ‘cause you’re trying to be tough and hard. And that’s what I tried to do. And it didn’t work. And that’s why I thought it was important to talk about it now.”

Jones, a former lawyer, removed Sargeant from his post as cabinet secretary for communities and children in November 2017 following allegations he had sexually harassed women. Also suspended from the Labour Party, he died four days later having not been given the details of the allegations. An inquest ruled his death a suicide.

While a tragedy for his family – who have not since spoken with Jones – the death also sparked some ugly blood-letting within Welsh Labour, with a series of briefings, leaks and broken friendships.

“The situation was very difficult, of course, in 2017, people had divided loyalties, they didn’t know which way that they should go, but a lot of that has settled,” says Jones.

“The tragedy is that it was difficult enough as it was, particularly for the family, but it was made worse by some individuals… who just made life hell for any number of completely unconnected people as they tried to settle grudges. And that made things worse for the family and for everybody else.”

There is much else personal in the book. Jones’ wife, Lisa, deals with an incredibly cruel string of illnesses, while at one point one of their two adopted children starts to resent her status as she enters her teenage years (“My daughter had, as it were, full editorial control over that” appearing, says Jones). It is, I say as someone who covered Jones’ rise to the top and first few years in office as a correspondent based in the Senedd, difficult to reconcile with the man who gave nothing of himself away as first minister.

“I think that’s a lot to do with my lawyer’s training, if I’m honest with you, because one of the things you’re taught as a lawyer, you know, is ‘be in control, be in control’,” he says.

“People want you to be in control, they want you to be somebody who comes over as having a grip on things.”

One of the things that Jones, who spent nine years as first minister, stresses in the book is his caution on the Brexit vote. Hindsight is 20/20, of course, but he writes of having done “everything short of getting down and begging David Cameron not to hold such a referendum six weeks after our [Senedd] election in Wales”.

He says now: “What you have to remember is the referendum was in June, we’d had an [Welsh assembly, now parliament] election in May, as had the Scots, as had London, and I said to him, ‘David, you can’t take risks with this. You need people campaigning, and our people are on their knees. We’ve had three months and longer of an election campaign, you can’t ask me to go out again and run a referendum campaign’.

“And the problem was you couldn’t start the referendum campaign until after the election. You spend time knocking lumps out of each other in different political parties, you can’t suddenly work together at the same time as part of a different campaign. It doesn’t work that way.

“I said to him, it’s got to be September, you’ve got to give people time to recover from the elections in Scotland and Wales, but I just don’t think he… I think he thought he could do it all himself, bluntly. In his mind he’d won in Scotland and he could do the same thing again.”

Jones got worried, he says, two days before the vote, in the heartland Labour territory of Blaenau Gwent, as voter after voter told him they were voting to leave.

“People were saying to me ‘don’t worry, we’re still Labour, but we want to kick David Cameron’. That’s what they wanted to do,” he says. It came despite West Wales and the Valleys benefitting disproportionately from EU structural funding over many years.

“When you said to people, ‘look, we’ve had all this money’, they’d simply say ‘yeah, but we’ll get that anyway, it’ll come from somewhere’. It was blind faith for a lot of people – and of course that question still hasn’t been resolved.”

There’s an artfully constructed line in the book when Jones writes of “what was perceived by the public as a lukewarm approach from Jeremy Corbyn”. Which begs the question – is that how Jones perceived it?

“Well, it could have been stronger,” he concedes. “But then I did share a platform with him in King’s Cross where he was robust in terms of defending EU membership. So I think Jeremy was torn between a natural Euroscepticism that exists in his strand of the party, that the EU is a way of preventing the UK from applying the kind of policies that he would want – that was part of him – while at the same time understanding that the majority of the membership was in favour of EU membership. And I think he did struggle to get the balance right in that regard.”

Now, while the UK party is back under a leadership more Jones’ flavour, he says it’s “not free of its tensions, let’s be honest”, and calls for Corbyn supporters to back Keir Starmer.

“I supported Jeremy when he was leader – not once did I call for him to stand down, not once did I look to undermine him.” he says.

“And I’m hugely supportive of Keir as well, and it’s hugely important that those who would not have been natural supporters of Keir get behind him rather than criticise him publicly. We are, after all, looking at being in government in the UK, not to be a kind of pure debating society.”

Now, as a backbencher in the Welsh parliament, he has looked on as Boris Johnson’s government has struggled, throughout the pandemic, at the notion that the devolved administrations have huge responsibilities in their nations.

“I’ve got to say, I was surprised at the extent of the powers as well, and I’m a bit of a constitutional anorak,” he admits. “Especially the quarantine regulations.

“But it does show that a lack of a proper decision-making body in the UK has not served us well. There’s no forum where governments can sit down and agree a common plan. And the reality was that England decided to go its own way in many areas and, you know, said ‘you either follow us or you don’t’.

“Well, that’s not the way things work anymore. We don’t follow England blindly, which is the way things were in the past.”

He thinks the pandemic has strengthened the need for a written UK constitution, he says.

“As long as you outline who does what very clearly and you have an arbiter, a court to settle disputes, it can be done. Canada does it quite happily, thanks very much, and Australia.

“You pool sovereignty, so you say each of the four nations is sovereign, but in some areas that sovereignty is pooled, defence being one obvious example, border and immigration control being another example. You have four separate parliaments, and you have one overarching UK parliament which deals with those matters which are agreed are UK matters. But it’s not sovereign.” The House of Commons could become the English parliament and the Lords the federal parliament, he suggests.

Much has been said in Wales since Jones, who flirted very briefly with Plaid Cymru in his youth, stepped down having become “indy-curious”, or at least having softened his line on independence.

Indeed, when we discuss it, it’s technical issues – Wales having no credit record to borrow money, having to go through England to access the European market – he focuses on, rather than the emotional pull of the Union.

“There’s no doubt that feeling for independence has grown,” he says. “It’s particularly strong with young people. There is an element of it within the Labour Party itself amongst young people who are open to the idea of independence.

“And we’ve seen in the polls independence is at an historic high – still, of course, a minority, still talking about a third of the electorate, but it’s where Scotland was 20 years ago. That’s what concerns me. And unless there is a serious alternative on the table to what we have now, I think that call for independence will grow. I’ve been surprised by the number of people who’ve been against independence all their lives who’ve changed their minds.”

He’s not wildly impressed with the prime ministers he had a unique insight into. Cameron “had a sense of self-assuredness that in the end did for him, with the referendum”. Theresa May was “very robotic… if you tried to make small talk with her, I just got the impression sometimes she thought it was some kind of trap”.

Now he is a former leader too, stepping down from the Senedd next year. He plans to focus on academic, business and broadcasting work and “it would take a lot of persuasion for me to go to the Commons, I have to say” – although, interestingly, I didn’t actually ask that.

But he couldn’t have a bigger post-politics blow than that he’s had already. Excited to have been asked to go on Celebrity Mastermind, staff in his office drew lots to see who would have to break the news to him that he’d been bumped – in favour of Bez from the Happy Mondays.

“I was bumped off,” he says, clearly disappointed. “No explanation. My specialist subject, actually, was Welsh Rugby from 1969 to ‘79. And I got bumped off.

“Well, there it is. There are always new opportunities.”

● Not Just Politics is published by Headline Accent, priced £20

● For confidential support the Samaritans can be contacted for free around the clock 365 days a year on 116 123