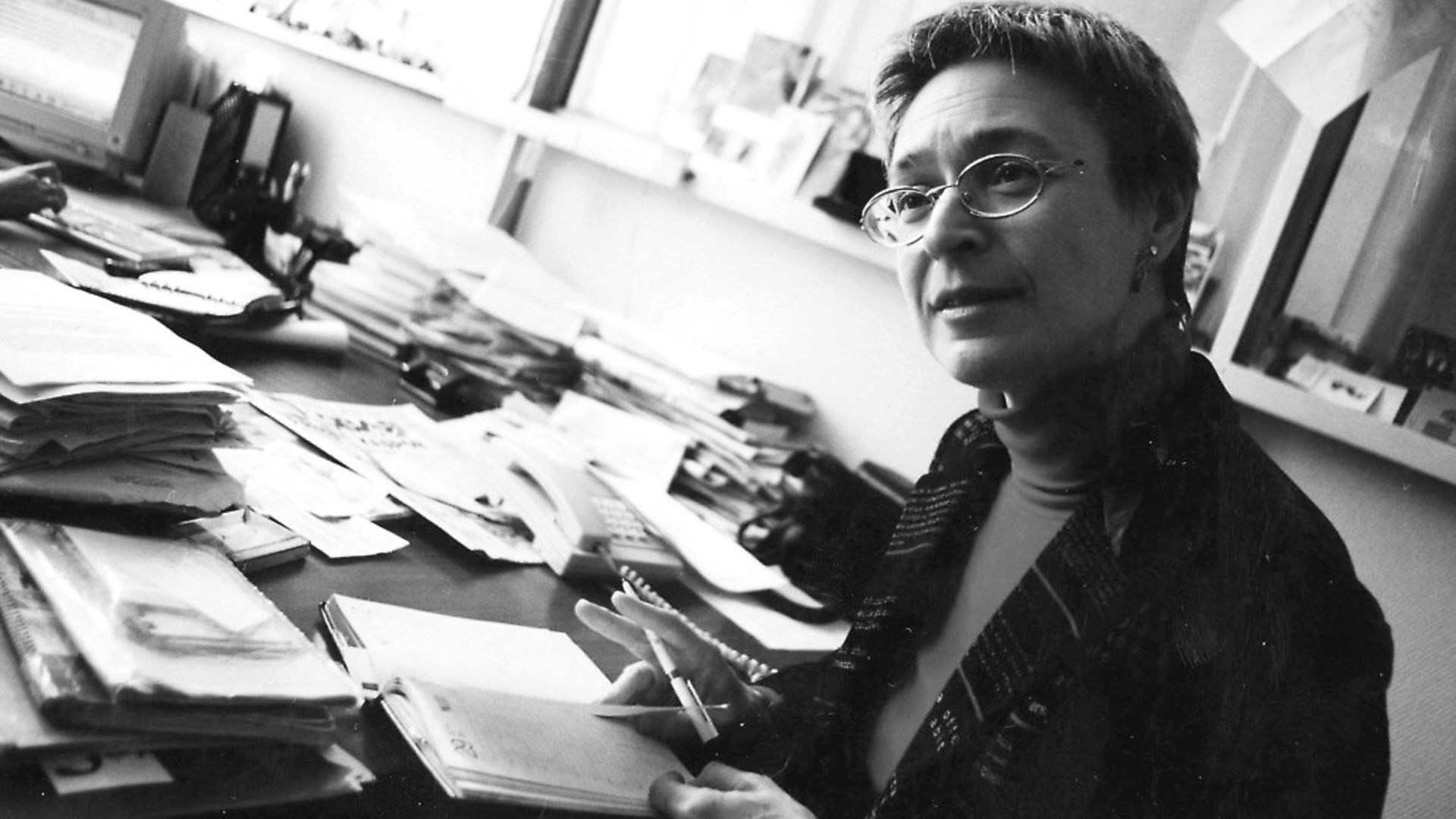

CHARLIE CONNELLY examines the life of Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, August 30, 1958 – October 7, 2006

On the day she died Anna Politkovskaya, for once, had domestic matters on her mind.

She was still coming to terms with the sudden death a fortnight earlier of her father Stefan, who had collapsed from a heart attack as he left a Moscow metro station on his way to visit his cancer-stricken wife Raisa in hospital.

A week before Politkovskaya died her mother had undergone major surgery, after which the journalist and her sister Elena had rotated bedside shifts, keeping Raisa company through her recuperation and sharing their grief for a husband and father.

Anna was supposed to be at the hospital that chilly, damp Saturday at the beginning of October 2006, but she’d had to switch with Elena as her pregnant daughter was moving temporarily into her Moscow apartment that day while her own home was prepared for the new arrival.

So preoccupied was Politkovskaya with family matters that when she went to the supermarket that afternoon she didn’t notice the tall man in the cap and his female companion following her at a distance as she pushed her trolley around the shop. She drove home, parked outside her apartment building and lifted as many bags as she could carry out of the boot of the car. Taking the lift up to her apartment, she left the bags outside the door and descended to the ground floor to collect the rest of her groceries.

When the lift door opened the tall man in the cap from the supermarket was standing there. He raised a pistol and shot three times, two bullets hitting Politkovskaya in the chest, the third hitting her in the shoulder. She was probably dead even before she hit the floor but the assassin made sure with one last bullet to her head before dropping the gun next to her, walking calmly out of the building and disappearing into a blustery, darkening afternoon. It was October 7, 2006, Vladimir Putin’s 54th birthday.

‘She was incredibly brave,’ wrote her newspaper Novaya Gazeta in tribute. ‘Much braver than any number of macho men in their armoured jeeps surrounded by bodyguards. She regarded any injustice, regardless of whom it involved, as a personal enemy.’

On her laptop at the time of her death was an unfinished article detailing the latest human rights abuses she’d discovered taking place in Chechnya, a topic to which Politkovskaya had devoted herself in the last years of her life that made her many powerful enemies. In that final piece, published posthumously by Novaya Gazeta, Politkovskaya wrote of the torture of a Chechen man by security forces loyal to Ramzan Kadyrov, the pro-Russian prime minister of the Chechen republic and a regular target of Politkovskaya’s pen.

The man who was tortured, she said, was an innocent civilian forced into a false confession in order that Kadyrov’s pro-Putin regime looked as if it was capturing rebel fighters. This latest man, she wrote, was one of a ‘conveyor belt of organised confessions’.

Politkovskaya had joined the independent Novaya Gazeta in 1999, the same year the second Chechen war began, and for the rest of her life went after Kadyrov and Vladimir Putin with relentless zeal. As well as her journalism she produced two books on the Chechen conflict, 2001’s A Dirty War: A Russian Reporter in Chechnya and A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches From Chechnya.

In 2004, two years before her death, she wrote Putin’s Russia, a visceral condemnation of the man and his regime. Referring to his time as a Soviet KGB agent before entering politics, for example, she wrote of how ‘he persists in crushing liberty just as he did earlier in his career’. Such strong and open criticism left Politkovskaya under no illusions regarding the danger in which she had placed herself.

‘I am a pariah,’ she said a few months before her murder. ‘That is the result of my journalism through the years of the second Chechen War and of publishing books abroad about life in Russia.’

Politkovskaya was the 13th journalist to be murdered or die in mysterious circumstances in Putin’s Russia and even then it was far from the first attempt on her life. In 2001, tipped off that a Russian military officer named in a human rights abuses story was on his way to find her, Politkovskaya took the threat seriously enough to move temporarily to Vienna.

Shortly after her departure a woman of similar appearance was shot and killed outside her apartment building. The same year she was detained by Russian troops in Chechnya and held for three days, during which she was subjected to threats and a mock execution.

In 2004 Politkovskaya became gravely ill after drinking tea on a flight from Moscow to North Ossetia, where she had been asked to help negotiate with a Chechen nationalist group who had taken more than 1,000 people hostage, most of them children, at a school in Beslan. She eventually recovered after being flown back to Moscow for treatment but all relevant test results and medical records went missing immediately afterwards.

Still she was not to be deterred.

‘As contemporaries of this war, we will be held responsible for it,’ she wrote of her unshakable resolve to expose Russian human rights abuses in Chechnya. ‘The classic Soviet excuse of not being there and not taking part in anything personally won’t work. So I want you to know the truth, then you’ll be free of cynicism.’

Politkovskaya could have opted for a much easier path. Both her parents had been diplomats at the United Nations in New York, meaning she was born not only into the Soviet elite but also qualified by birth for a US passport. The connections garnered by the former could have led to a comfortable life and career, the latter gave her a raft of options outside Russia, but instead she chose the most difficult and dangerous path possible: independent, campaigning journalism inside Russia.

On leaving school she earned a place on the prestigious journalism degree course at the Moscow State University, where she developed the streak of fearless independence that would characterise her life by writing her dissertation on the exiled Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva. On graduation Politkovskaya worked first for the national daily Izvestia, then spent most of the 1990s at Obshaya Gazeta under editor and co-creator of Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost policy Yegor Yakovlev.

It was when she joined Novaya Gazeta that she truly earned her spurs as a hardworking, investigative journalist and developed the reputation that cost her her life.

Perhaps the greatest tribute to her work came inadvertently from Vladimir Putin himself. Speaking three days after Politkovskaya’s murder – for which five men are now in prison without any acknowledgement of who ordered the hit – the Russian president said: ‘The degree of her influence over political life in Russia was extremely insignificant. She was well-known in journalistic circles and among human rights activists in the West but I repeat, her influence over political life in Russia was minimal.’

Such a cack-handed attempted dismissal betrayed just what a thorn in his side Politkovskaya had been: in a nation of 140 million people she had been one of a handful brave enough to raise their voice in public against the injustices of the Russian regime. She knew the risks she was taking and the danger she faced but refused to be cowed.

In October 2002 a group of 40 armed Chechen militants with bomb vests strapped to their bodies took over the Dubovka Theatre in Moscow, holding 850 people hostage. On the third day of the siege Anna Politkovskaya agreed to enter the theatre alone and attempt to engage with the captors.

‘I am Politkovskaya,’ she called out as she entered the lobby, walking fearlessly into mortal danger. ‘Can anyone hear me? I am Politkovskaya!’