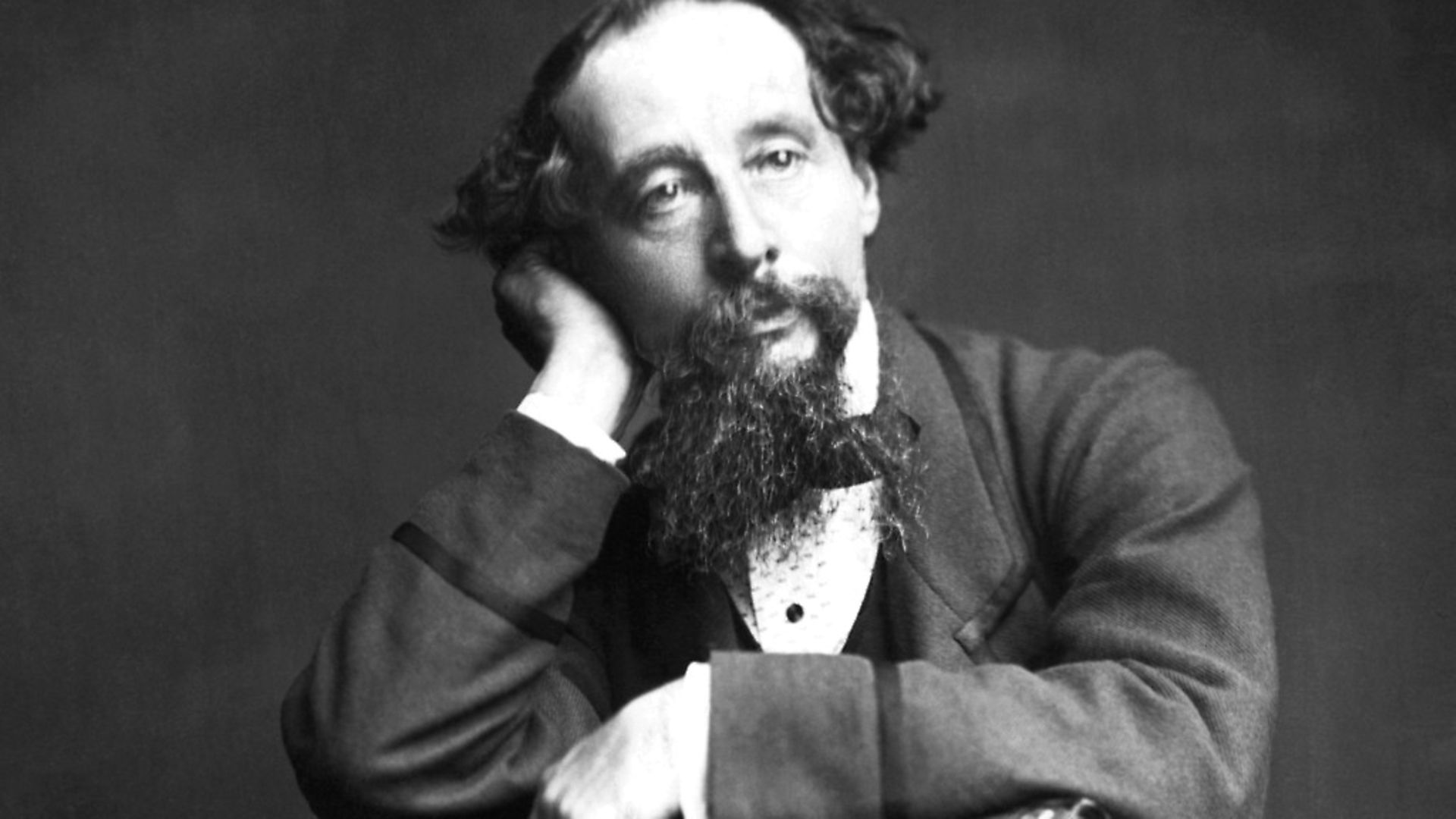

CHARLIE CONNELLY on how the great author ended up at his final resting place, far from where he had hoped to be.

‘Charles Dickens, the great American romancer, died yesterday of apoplexy. He was the Walter Scott of America.’

As bad takes go, that report of the demise of the great novelist that appeared in a New Orleans newspaper really is a doozy. Believe it or not, it wasn’t the worst either. That accolade goes instead to a paper in Mississippi, which solemnly noted the passing of ‘George Dickens, the well-known author of Boz and The Mystery of Druidism’.

Fortunately Dickens’ death on June 9 1870, 150 years ago this week, was better marked elsewhere, triggering a global wave of sadness at the demise of the man many argue was the greatest fiction writer in the history of literature in English.

Dickens’ work remains popular largely because its themes of compassion and humanity in the face of crippling social injustice endure, comprising stories whose emotional impact resonates today. Dickens’ voice speaks clearly to us a century and half after it was silenced making it perhaps appropriate his funeral was not dissimilar to those taking place across the country during the current pandemic. The circumstances couldn’t have been more different, however.

Dickens, 58 when he died, had spent June 8, 1870 working on what would turn out to be his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, at his home at Gad’s Hill, near Rochester in Kent. That evening he suffered a stroke at the dinner table, lingered for 24 hours and despite the attendance of John Russell Reynolds, the nation’s leading specialist in neurological disorders who had rushed down on the train from London, died in the early evening of June 9 without regaining consciousness.

‘One whom young and old, wherever the English language is spoken, have come to regard as a personal friend is suddenly taken away from us,’ lamented the Times the following day. ‘Charles Dickens is no more.’

The news spread quickly across the country and to the world beyond, notably America where he had conducted a number of highly successful reading tours. French newspapers published solemn tributes, comparing him favourably to their own Honoré de Balzac. Queen Victoria sent a telegram of condolence to the family from Balmoral. Detailed descriptions of his last hours – ‘his limbs were flaccid until half an hour before death, when some convulsion occurred’ – were published in a manner recognisable today: Dickens’ celebrity was so great even something as intimate as death was public property.

No detail was too obscure or too personal, not even the relative dilations of his pupils in his last hours (the right was more dilated than the left, fact fans). Celebrity, then a fledgling concept in the form we know today, triumphed over personal dignity.

His funeral, however, was another matter. As the most famous person in the country after the Queen herself, Dickens’ passing cried out for spectacle, the opportunity for the country to say goodbye to its greatest writer in the most sumptuous manner of mourning available. Inconveniently, the writer himself sought to vanish with as little brouhaha as possible. His will was unequivocal on the matter:

‘I emphatically direct that I be buried in an inexpensive, unostentatious, and strictly private manner, that no public announcement be made of the time or place of my burial, that at the utmost not more than three plain mourning coaches be employed, and that those who attend my funeral wear no scarf, cloak, black bow, long hatband, or other such revolting absurdity,’ it read. ‘I direct that my name be inscribed in plain English letters on my tomb without the addition of ‘Mr’ or ‘Esquire’. I conjure my friends on no account to make me the subject of any monument, memorial, or testimonial whatever. I rest my claims to the remembrance of my country upon my published works, and to the remembrance of my friends upon their experience of me.’

While he micromanaged his send-off to the extent of specifying a maximum number of carriages for mourners, nowhere in the document had Dickens identified precisely where he wanted to be buried.

Close friends and relatives said he’d talked of being laid to rest near Gad’s Hill, in the graveyard of a parish church such as those at Cobham or Shorne, or perhaps the small cemetery in the former moat at Rochester Castle. None of these were open for new burials, the family was told.

Instead Rochester Cathedral looked to be the best candidate as Dickens’ final resting place. A bit snazzier than he’d had in mind, for sure, but it was still local and as long as nobody turned up in a hatband of more than medium length Dickens probably wouldn’t end up spinning in his freshly-dug grave. The Dean and Chapter of the cathedral were amenable and, with the cemetery in the grounds of the cathedral full, they prepared a grave in the Lady Chapel inside the building itself.

Now, given that Dickens had, for the final 13 years of his life, conducted a clandestine relationship with the actress Ellen Ternan which began when he was 45 and she 18, and treated his wife Catherine abominably for most of their married life, placing his remains in a chapel devoted to the mother of Christ might have raised a wry eyebrow or two among the very few people who knew about Dickens’ closely-guarded romantic shenanigans. As it turned out, the Kentish tomb would remain unoccupied. From the moment news broke of Dickens’ death plans were afoot for a more glamorous location.

In the milky dawn light of June 14, 1870, Dickens’ body was taken by hearse from Gad’s Hill to Rochester railway station and placed on a specially arranged train which travelled at a stately pace to Charing Cross station in central London, arriving at nine o’clock on the dot. A small band of mourners met the coffin and followed it in the specified three carriages to Westminster Abbey where Dickens was to take his eternal rest in the famous Poets’ Corner.

‘The wish of the people had prevailed,’ said the following day’s Times, ‘and Charles Dickens rests in the Abbey church of St Peter in Westminster.’

According to the Manchester Guardian it was ‘owing to the universal wish that he be laid to rest with other worthies of English literature’ that Dickens was buried not as he might have hoped in the sun-dappled peace of a country churchyard but in the cavernous abbey at the heart of London and of British history.

There appears to be little documentary evidence for this decision being anything like the will of the people. There were no letters to the newspapers demanding Dickens’ interment among the literary great and good and the only mention of its possibility came in a speculative Times leader on June 13, the day before the funeral. The Daily News even noted the day after the ceremony that, ‘the announcement in the evening papers yesterday afternoon that the interment had taken place in Westminster Abbey yesterday morning took the public by surprise’.

Recently, however, Dickens scholar Professor Leon Litvack of Queen’s University, Belfast, discovered the Westminster burial was cooked up between the author’s friend and posthumous biographer John Forster and the Dean of Westminster Abbey himself, Arthur Stanley. Forster felt a simple rural burial would not provide a grand enough climax to Dickens’ life, not to mention the book he was writing, while Stanley had been hoping for a marquee name to bury in order to re-establish Poets’ Corner as a national shrine, there having been no true literary superstars interred there since Dr Samuel Johnson in 1784. The whole ‘wish of the people’ line was an invention; the population had expressed no strong collective opinion either way.

Despite the scheming of Forster and Stanley commencing almost as soon as Dickens breathed his last, the excavation of a grave at Westminster didn’t begin until after midnight on the Monday, barely nine hours before the small funeral cortege arrived.

It’s unlikely from the wording of his will that Dickens would have had Westminster Abbey in mind for his eternal rest. For one thing, a quiet country churchyard would have been easier for Ellen Ternan to visit unobserved, for another his distaste for the mawkish faff involved in Victorian funerals was well documented. If his will hadn’t make it clear enough, a year almost to the day before his death he’d declined an invitation to inaugurate a new monument at the grave of essayist and poet Leigh Hunt in Kensal Green cemetery in north London because he had ‘a very strong objection to speech making beside graves’ and ‘the idea of ever being the subject of such a ceremony is so repugnant to my soul that I must decline to officiate’.

He did get his desired no frills, sparsely attended funeral though, one similar in such respects to the many happening across the country in these pandemic times, 150 years on.

Barely a dozen friends and relatives, including Forster and Wilkie Collins, stepped from the carriages and entered the abbey, none of them clad in what one report called ‘the dismal frippery of the undertaker’ as per instructions. Reports noted 14 mourners but gave only 13 names – was the missing name Ellen Ternan, omitted for reasons of decorum?

Either way Dickens’ grave had been prepared at the feet of George Frideric Handel and next to that of Thomas Macaulay (in the following century both Thomas Hardy and Rudyard Kipling would be placed alongside Dickens). Dean Stanley officiated and other than a single voluntary on the organ there was no music, no hymns, not even spoken responses to the funeral oratory.

The grave was left open for the day to allow people to pay their respects as the word spread through the city, especially once the evening papers arrived on the streets.

One thousand people were still waiting outside when the abbey doors closed at six o’clock that evening and it would be October, more than three months after the occasion, before the floral tributes, from wreaths to single blooms plucked spontaneously from buttonholes, would be removed to reveal the simple brass inscription laid into the dark stone, displaying just his name and the dates of his birth and death.

Somewhere at the back of the crowds paying tribute, maybe there was a Mississippi voice asking in a stage whisper whether this was the place where they buried George Dickens, the Mystery of Druidism guy.