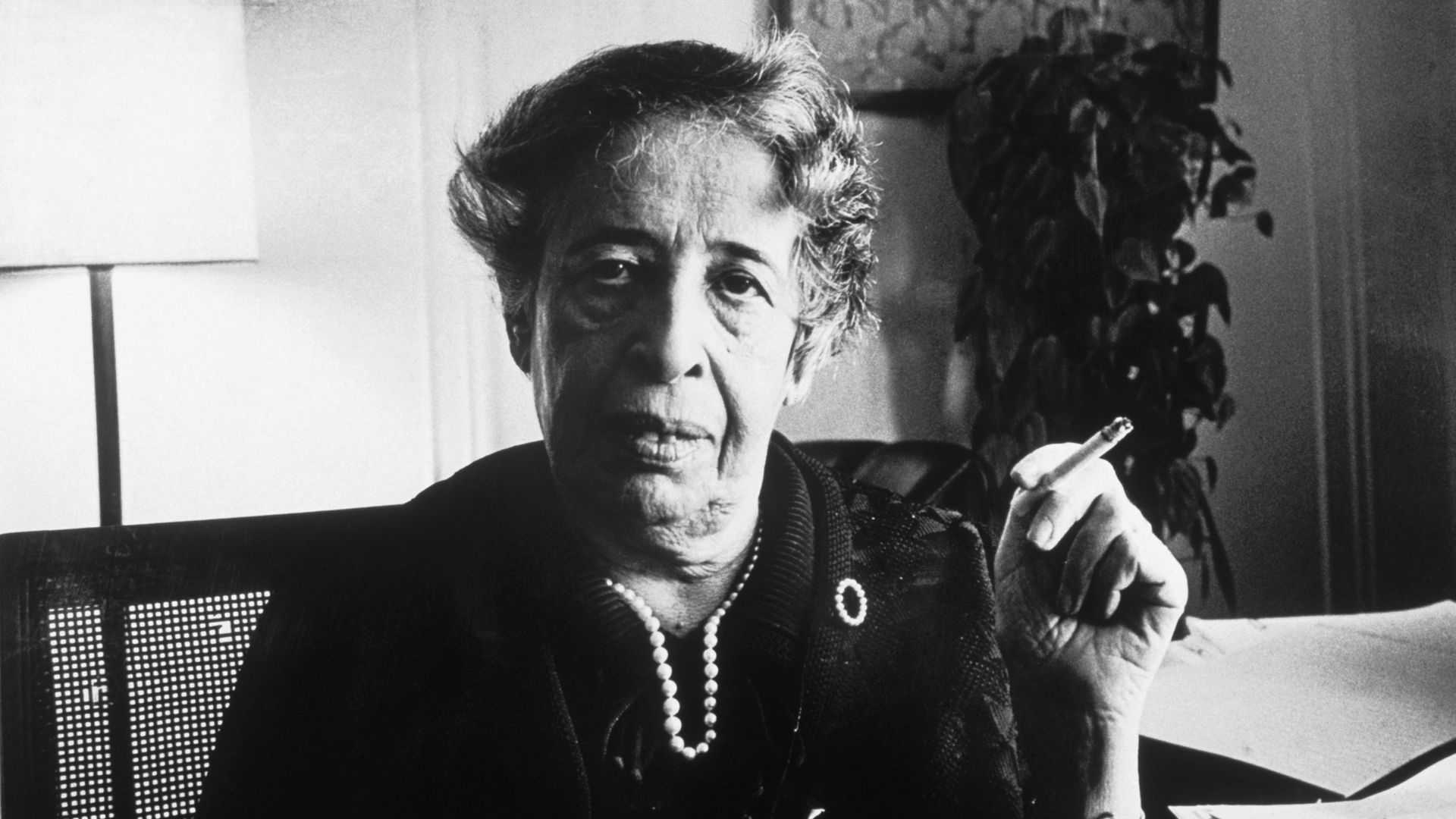

CHARLIE CONNELLY profiles the thinker Hannah Arendt.

In 1960 Hannah Arendt noticed that Adolf Eichmann, one of the key architects of the Holocaust, was due to stand trial in Israel the following year. A decade earlier Arendt had published her groundbreaking book Origins of Totalitarianism, in which she examined the roots in anti-Semitism and 19th century imperialism of both Nazism and communism, dubbing them a novel form of government for using terror to control an entire population rather than just eliminate political opponents.

Seeing Eichmann in the dock, she felt, would provide first-hand experience of her theories in action. The New Yorker commissioned a series of pieces and Arendt was able to attend six weeks of Eichmann’s five-month trial.

The first thing she noticed as she sat just a few feet away from Eichmann was that he didn’t look much like the personification of evil. In the dock he appeared entirely unremarkable, middle-aged, balding, wearing spectacles with misty lenses, listening glassy-eyed to the translations coming through his headphones and responding with droning inarticulacy. It didn’t take long for Arendt to realise that far from the living embodiment of pure evil, Eichmann could have passed for a low-level bureaucrat at any company anywhere in Europe. He was, as Arendt wrote in the New Yorker and then her international bestseller Eichmann in Jerusalem, “terribly and terrifyingly normal”.

The phrase everyone took away from the book was “the banality of evil”, of which Eichmann at his trial was Arendt’s archetype. He was not a fanatic and didn’t express any kind of ideology. He displayed no guilt for his actions but didn’t betray a particular hatred for the Jews he had dispatched in their thousands to the camps and ultimately to their deaths. His bureaucratic passivity and failure to engage with the nature of his crimes, Arendt wrote, was what made him so terrifying. It wasn’t malice that drove him to unspeakable acts, she concluded, more an unthinking loyalty to a system. It was death by paperwork.

Her criticism wasn’t limited to Eichmann and the Nazis. Arendt, who was Jewish and had fled Germany first to France and then to the US to escape the coming tyranny, also questioned the morality of Jewish community leaders and their co-operation with the Judenräte, the Jewish councils formed by the Nazis to assist with the administration of the ghettos and, by extension, the Holocaust itself.

“To a Jew this role of the Jewish leaders in the destruction of their own people is undoubtedly the darkest chapter of the whole dark story,” she wrote. She even raised questions concerning the legality of the trial and the manner in which it was carried out, noting how “the audience at the trial was to be the world and the play the huge panorama of Jewish sufferings”.

For Arendt the Holocaust was a failure in human morality that went way beyond political doctrines, something confirmed for her, she said, “when we heard about Auschwitz. Before that we said, well, one has enemies, that is natural. Why shouldn’t people have enemies? But this was different. It was as if an abyss had opened. Amends can be made for almost anything at some point in politics. But not for this”.

Eichmann in Jerusalem caused a sensation when it was published in 1963, earning as much criticism as praise. The American writer Mary McCarthy, who became a close friend of Arendt, called the book “a paean of transcendence, heavenly music, like that of the final chorus of Figaro or the Messiah”, while Saul Bellow dismissed it as, “making use of a tragic history to promote the foolish ideas of Weimar intellectuals”.

Arendt took the mixed reaction to her treatment of a such a vital, emotional subject that will always provoke revulsion and terror, largely in her stride, growing frustrated only when she felt her views were being misrepresented. She always rejected labels like ‘theorist’ and ‘activist’, preferring the term ‘independent thinker’ instead.

One reason she proved to be controversial to many reviewers and commentators was that she was impossible to pigeonhole into one political standpoint. Her unwillingness to expand her philosophical role into one of any kind of action also baffled many, leading her to comment that “while there are other people who are primarily interested in doing something, I am not. I can very well live without doing anything. But I cannot live without trying to understand whatever happens”.

Hannah Arendt was the only child of Paul, an engineer, and Martha, a musician, secular Jews from families that had fled pogroms in Russia and Lithuania during the mid-19th century. She was born in what’s now a suburb of Hanover but the family moved to Königsberg, now Kaliningrad, in East Prussia when she was four years old. Her father, who died in an asylum from syphilis when his daughter was seven years old, kept a well-stocked library particularly strong in the classics, in which Hannah immersed herself almost as soon as she could read.

She studied under Martin Heidegger in Berlin and at the age of 17 embarked upon a relationship with him, but by 1929 she had her doctorate and had met and married the philosopher Gunther Stern. The couple settled in Berlin where at the start of the 1930s Arendt became increasingly political in her research and writing, most notably regarding Germany’s increasing anti-Semitism. In 1933 a librarian at the Prussian State Library reported her to the authorities for assimilating anti-state propaganda – she was compiling examples of state-sponsored anti-Semitism – leading to the arrest by the Gestapo of Arendt and her mother. Released on bail the pair fled Germany, crossing the Erzgebirge Mountains into Czechoslovakia under cover of darkness, making their way to Prague then taking a train to Geneva. Arendt took a job with the Jewish Agency for Palestine at the League of Nations then after a few months moved on to Paris where she rejoined her husband, although the couple had separated by then, and would spend the rest of the 1930s working for Jewish charities and political organisations.

In 1940, ahead of the German invasion of France, Arendt was briefly interned as an enemy alien but managed to secure her release and make her way through Spain and on to Lisbon where, with her mother and new husband Heinrich Blücher, she found passage on a ship to New York. Once in the US Arendt was appointed research director of the Conference on Jewish Relations and in 1949 became executive director of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, which sought to salvage Jewish writings suppressed by the Nazis.

Origins of Totalitarianism confirmed her status as one of the foremost philosophers of her time and opened up to her the world of US academia. In 1959 she was appointed visiting professor of politics at Princeton, the only woman professor in the entire university. “I am not at all disturbed about being a woman professor,” she said, “because I am quite used to being a woman.”

Arendt published The Human Condition in 1958 and On Revolution five years later, which along with her books on Eichmann and totalitarianism ensured her place as one of the 20th century’s foremost thinkers. Unsurprisingly perhaps, Arendt’s work has returned to the spotlight in recent years, receiving renewed attention in the US in particular.

“In the months after Trump came to power, Arendt became something like the patron saint of liberal angst,” is how the New York Review of Books put it when shops across the nation reported Origins of Totalitarianism selling out, at 600 pages and nearly 70 years old an unlikely bestseller. “The banality of evil”, effectively her catchphrase, was a phrase widely disseminated again, as was her suggestion that “the ideal subject of a totalitarian state is not the convinced Nazi or Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (that is, the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (that is, the standards of thought) no longer exist”. That she wrote this in 1953 demonstrated the originality of her ideas and philosophies, that her work was, in some ways, timeless.

In her later years she became friends with the poet W.H. Auden. On Auden’s death in 1973, two years before Arendt herself died suddenly from a heart attack while entertaining friends at her New York apartment, she wrote an elegant tribute, describing how they “met at an age when the easy, knowledgeable intimacy of friendships formed in one’s youth can no longer be attained, because not enough life is left, or expected to be left, to share with another”. She quoted one of her favourites among his poems, lines that seem to sum up Arendt herself and the renewed relevance of her work in the 21st century.

Time will say nothing but I told you so.

Time only knows the price we have to pay;

If I could tell you I would let you know.