CHARLIE CONNELLY on a surreal awards ceremony and some sublime literature.

We’ve become so used to this year’s General Weirdness that a Booker Prize ceremony without the crescendo hubbub of increasingly pissed publishers barely raised an eyebrow. The General Weirdness dictated that this year the bunfight at the Guildhall would be replaced by an audience-free, socially-distanced affair at The Roundhouse in London streamed live by the BBC.

The Booker is the highlight of the publishing year, certainly if you define your highlights in terms of free grub, booze and goodie bags, and invitations to the ceremony are exclusive enough to make Wonka golden tickets look like discarded masks in a puddle. This year there were no invitations, no free nosebag, no magically refilling bottles of chardonnay and no totes full of snacks, vouchers and proof copies of next year’s Booker contenders.

This year there were no cameras zooming in on a stunned winning author being thumped on the back and applauded to the stage before giving a disbelieving, long-rehearsed acceptance speech that’s ignored by an audience frowning at their phones, frantically tweeting and texting the news to everyone they can think of. So many phones start vibrating immediately after the Booker announcement that seismographs across the globe register a small earthquake centred in north London.

Instead the BBC had to devise a new way of building suspense and keeping everyone entertained in the absence of an audience and with rigid social distancing in place: the perfect ingredients for a panache vacuum. Books aren’t exactly sass central at the best of times either, and novelists aren’t really renowned for their top-hat-and-cane showbiz élan. As an entertainment challenge we were in the realm of Rudy Giuliani’s Poetry Hour.

“It will be a starry night here,” promised BBC Radio 4 Front Row presenter John Wilson, bounding into a wide shot of a Roundhouse empty but for a socially-distanced string quartet and a line of six tall, white plinths, each with a shortlisted book placed on top in the kind of display that suggested a black-clad thief was about to descend on a wire and steal them.

With his silver hair and exquisitely fitted grey suit there was an air of Anderson Cooper or Roger Sterling from Mad Men about Wilson, both of which boded well. Seamlessly and with an expansive gesture he introduced the six shortlisted authors, all of whom were displayed in two lines of three on a giant screen sitting at home in front of their laptops, waving awkwardly as if in some dystopian literary version of Celebrity Squares.

Then Wilson introduced Kazuo Ishiguro, Nobel Prize laureate and winner of the 1989 Booker for The Remains of the Day. He too appeared on a big screen, beamed live from his home where he sat pressed up against a bookcase in a manner that suggested the whole lot would come down on him if he moved.

“The Booker’s a big deal,” he illuminated, concluding that “it’s like a dating agency, it’s introducing a book to the reading public, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.”

Next up was Camilla, the Duchess of Cornwall, whose poppy suggested her contribution was recorded well in advance of the event. Standing formally at a lectern she expressed her “huge pleasure to be here tonight, albeit in a disembodied form”. A keen advocate of reading, the Duchess praised the role of books in keeping up the spirits of the nation during this year’s troubled times.

Through reading, she said, “we can travel, we can escape, we can explore, we can laugh, we can cry,” after which I thought she said reading allows us to “grapple with life’s mistress”, which seemed to demonstrate impressive self-awareness, but she’d actually said “mysteries”.

Wilson then facilitated a three-way discussion with Margaret Busby, who chaired this year’s judging panel, and Bernardine Evaristo, who won the 2019 Booker with the brilliant Girl, Woman, Other jointly with Margaret Atwood.

All three stood a considerable distance apart which combined with the dark background of the set to give the conversation an air of the final round of an intense quiz show.

Evaristo looked almost relieved to be stepping out of the spotlight to make room for the 2020 winner, and seemed to prefer this year’s lockdown style award to the “five-hour ceremony before the announcement last year”. When asked how the prize would change the winner’s life she said, “they’ll certainly find their lives will change” before adding, with a hint of ambiguity, “but they should enjoy the moment tonight”.

During the build-up a short, pre-recorded interview with each author was played before a passage from their book was read by an actor. This was probably the only part of the proceedings that didn’t really work, purely because the actors were acting. And boy were they acting. Every available nuance was wrung from every single word. They were really, really acting, like their lives depended on it, which would have been fine for a series of dramatic monologues with a beginning, middle and end but isn’t really appropriate for a couple of paragraphs taken out of context from a novel. Chalk one up for the traditional droning author reading there, I’d say.

Wilson’s starry night continued when Barack Obama loomed up on a screen. The Booker ceremony had been pushed back a couple of days so not to coincide with the publication of his memoir, but did he say thank you? Did he feck. Instead he just, you know, oozed presidential authority and easy charm, and made slightly self-deprecating jokes as he praised the benefits of reading and namechecked some black authors associated with the award and basically just Obamaed the lot of us into a gentle, purring haze inside the space of two minutes. Whether the pair of boxing gloves visible behind him was a reference to current events or – even better – some kind of challenge to the current incumbent, we’ll probably never know.

Then, at last, it was time for the announcement. As Margaret Busby emerged from the shadows to approach the lectern the string quartet struck up with Handel’s Hallelujah chorus – echoing the realisation of the audience that there would be no more actors frantically emoting – at which Busby gave that rare thing: a memorable speech by someone presenting an award.

She pointed out how there wasn’t a black Booker judge until 2015. She mentioned the diversity and literary youth of the shortlisted and indeed longlisted authors: four of the books on the shortlist were authors’ first novels, eight of the 13 longlisted books had been debuts. Ethiopia, India, Zimbabwe and Scotland were represented on the most diverse shortlist in the history of the prize.

She also casually mentioned that the judges had each read all of the 162 books submitted for the prize as if it was nothing, as if that wouldn’t leave you never wanting to see another book in your life, and we all briefly marvelled at how they’d managed to reduce that number to first 13, then six and, imminently, one.

All of which was just piling on the agony for the six authors, still displayed with epic cruelty on a giant screen, still trying to affect a combination of modest nonchalance about the result despite having thought about nothing else since the announcement was made, with mild enthusiasm to know the outcome. If this had been a cartoon they would have been looking down their laptop cameras with mouths replaced by wavy lines.

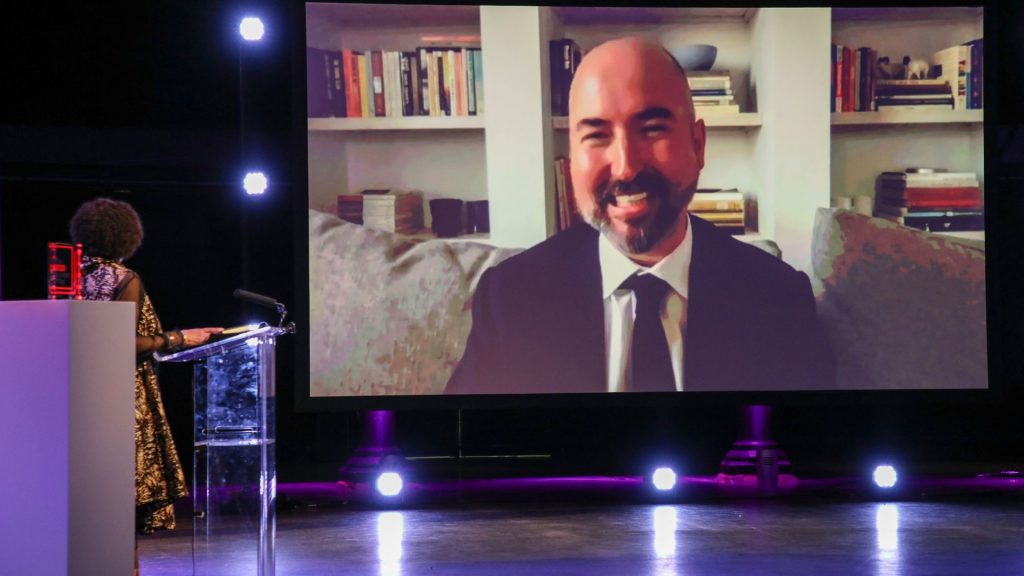

Then Busby reached below the lectern and produced something made of black cloth and for a brief moment I thought she was going to put it on her head and pronounce a death sentence, which I suppose was exactly how the authors were feeling by that stage. But no, it was a bag from which she pulled a copy of the winner, Shuggie Bain by Douglas Stuart.

On the face of it, a middle-aged bearded white bloke scooping the prize looks a bit like a return to the olden days for the Booker but this was something quite different. The story of Shuggie’s working class Glasgow childhood and youth coping with an addict for a mother echoes that of Stuart himself.

The author’s alcoholic mother died when Stuart was 16 and from such an disadvantaged background, not to mention his homosexuality in a particularly alpha male atmosphere, he managed to gain a master’s degree in textiles from the Royal College of Art, move to New York at 24, become one of the leading figures in the fashion industry and win the Booker Prize with his first novel, written in his spare time outside a demanding day job. When you add in that Shuggie Bain was rejected by 32 publishers before it was taken up, this is a hell of a story.

The big screen had cut immediately to Stuart’s delighted reaction, sparing us the sight of the other authors having to look really, really pleased despite their very souls seeping out through their feet and spreading across their immaculate wooden floors like the arterial blood of a murder victim. Or even, which would have been great telly, trashing their apartments while ranting with inventive swearwords at the injustice of it all.

Stuart becomes only the fifth author to win with a debut novel since the Booker began in 1969 and only the second Scottish winner after James Kelman, who won in 1994 with How Late It Is, How Late. Coming a week after Scotland qualified for the European Championships, their first tournament finals since 1998, November has been a pretty good month to be Scottish.

“Let me just invite you to say a few words,” said Wilson to Stuart’s giant delighted face on the big screen. “A speech,” he added, making sure the winner knew what was now expected of him.

“I know I’m only the second Scottish book in 50 years to have won,” he said, “and that means, I think, a lot for regional voices, for working class stories, so thank you.”

As Evaristo had hinted earlier, this was a lifechanging moment for Stuart, and not just in terms of the fifty thousand smackers in prize money heading his way. His sales will rocket and the next few weeks will be a whirl of interviews and attention ahead of a year of demands for appearances, signings, book reviews and endorsements, basically the absolute antithesis of the traditional writer’s routine. For the next year at least his life, in many ways, will no longer be his own.

“We’ll be speaking to Douglas at length on Front Row on Monday evening,” said Wilson, wrapping up the coverage. With a brief glance up at the face on the big screen, he added, “I’m not sure he knows that yet”.

FIVE GREAT BOOKER-WINNING DEBUT NOVELS

THE BONE PEOPLE

Keri Hulme (Picador, £10.99)

New Zealander Hulme saw off some tough shortlist opposition in Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing and Peter Carey to win the Booker in 1985 and become the first debut novelist to scoop the prize. The Bone People, like Shuggie Bain, was rejected by a string of publishers before being taken on by a small New Zealand feminist imprint who published just 2,000 copies. Thirty five years later it’s a million seller. A challenging read, it took Hulme 12 years to write in a victory for tenacity and trust in one’s own ability.

THE GOD OF SMALL THINGS

Arundhati Roy (Harper Perennial, £8.99)

Roy was 35 when The God of Small Things was published and scooped the Booker in 1997. It’s a semi-autobiographical account of an Indian family facing social and economic decline that has sold more than eight million copies and been translated into 42 languages. It led to Roy having to answer charges of obscenity in her home state of Kerala and endure criticism that her book only won because it was already a bestseller with positive reviews. Today, it’s regarded as a classic.

VERNON GOD LITTLE

DBC Pierre (Faber & Faber, £8.99)

“I was out of work in London at the time, due not only to a mystifying arts CV but the wrong hair and a shortfall of buzzwords,” said Australian writer DBC Pierre on how he came to write Vernon God Little, which beat Margaret Atwood among others to win the Booker in 2003. It also scooped the Wodehouse prize for comic fiction and the Whitbread prize for a first novel. The story of a troubled Texan teenager, the Booker judges called Vernon God Little “a coruscating black comedy reflecting our alarm but also our fascination with America”. Still topical, then.

LINCOLN IN THE BARDO

George Saunders (Bloomsbury, £8.99)

Saunders’ extraordinary and original account of trapped souls in the cemetery where Abraham Lincoln would make nocturnal visits to the grave of his recently dead son was an astonishing first novel. The Booker winner in 2017 Lincoln In the Bardo features 163 different character voices and manages to be at once a warm and human exploration of grief and a riotously funny book. “It sounds a little pathetic but for an artist I think validation is really helpful. Maybe you shouldn’t need it but I definitely do,” said Saunders as he became the second American winner since the prize was opened up to US authors in 2017.

SHUGGIE BAIN

Douglas Stuart (Picador, £14.99)

Already a bestseller before it won this year’s Booker, Shuggie Bain is a towering achievement for debut novelist Stuart, not least because the manuscript was rejected by more than 30 publishers before finding a home at Picador. In Shuggie and his alcoholic mother Agnes, Stuart has created two characters who live long in the memory of every reader. “Young boys like me growing up in 1980s Glasgow, this wasn’t ever anything I would have dreamed of,” said the author on winning the prize.