Long sceptical about whether such a phenomenon existed, CHARLE CONNELLY starts to wonder if there might be something in it after all.

I sat down to write this piece about writer’s block at eight o’clock this morning. It’s now 11.20am and I’m only just putting words onto the blank document that’s been sitting here open and unblemished for almost three and a half hours now. I’ve made a few cups of coffee, read a lot of news online, had a Kit Kat, done a bit of light washing up, whimsically remembered a book I liked when I was a kid then whimsically ordered it, had another Kit Kat, made a couple of comments under friends’ Facebook pictures that aren’t nearly as funny as I thought they were and completed two newspaper crosswords (not the cryptic ones). And now here we are. Some words on the page, at last.

Great, I thought, there’s a perfect way to start a piece talking about writer’s block. Except I’m not sure that it was writer’s block. I’ve never been entirely convinced that writer’s block exists. I think it might have just been, well, me.

Or was it? A year into the coronavirus restrictions many writers are bemoaning the fact that despite ostensibly experiencing less distraction during our national house arrest than ever before, they’re not producing anything.

I’ve been dreading the prospect that around a year from now we’ll be inundated with pandemic novels, whether addressing it directly, metaphorically, allegorically or tangentially. If the wind was blowing the right way from Stoke Newington, I fretted, you would hear the frenzied sound of clattering keyboards, like a landslip from a Scrabble tile mountain.

If recent pronouncements by some writers on social media and in a scatter of lip-chewing think pieces are to be believed we might actually be spared this glut of literary gloom. Indeed, there are signs that we might not have much to read at all on any subject because writers, it seems, aren’t writing.

“Stultified is the word,” novelist Linda Grant told a newspaper last month. “The problem with writing is it’s just another screen and that’s all there is. I can’t connect with my imagination. I can’t connect with any creativity. My whole brain is tied up with processing, processing, processing what’s going on in the world.”

Grant isn’t the only one. A cursory scroll through social media reveals a slew of writers concerned that thanks to the pandemic they either can’t seem physically to force anything onto the page or simply can’t think of anything to write. When you’ve travelled no further than the supermarket for months and have only had conversations with the people you live with and the postman inspiration can be hard to come by, even if you have a fascinating postman.

I’ve always suspected writer’s block to be an exaggeration at best, a bit of an affectation at worst. It’s a shutdown phrase tossed out to prevent further probing, a writerly way of saying ‘I haven’t done any work’.

Can it really be down to coincidence that we never hear of accountant’s block, firefighter’s block or solicitor’s block? Whatever your job or vocation there are always days when you don’t really feel like it, when your shoulders sag, when it’s just not happening. Surely you just plough on through and do what needs to be done, right? Why are writers the big exception?

If anything, I thought writer’s block was a product of privilege. There have been times when I’ve found it hard to sit down and batter away at the keys, but before I start thinking about some debilitating psychological block I take a quick look at my bank balance and, wouldn’t you know it, my typing fingers start going again. Both of them.

I can’t afford to have writer’s block: no writing means no income. Imagine being in the position where not writing anything for weeks, months or even years on end didn’t really affect your lifestyle, let alone threaten your solvency. While I aspire to swooning on a daybed complaining of writer’s block while peacocks gambol in the grounds outside, in the meantime I’m here in my freezing office in two pairs of socks and a Charlton Athletic beanie.

Writer’s block, I’d always thought, is a luxury indulged only by the wealthy. Yet viewing the increasing frustration currently expressed by writers of all ilks, genres and income levels, I’m starting to wonder whether I’ve been wrong all this time.

The term itself is a relatively recent one, coined during the 1940s by a Freudian psychiatrist named Edmund Bergler who was the first to study what he called “neurotic inhibitions of productivity” in writers. He soon ruled out popular theories of the time, such as writers possessing a finite amount of inspiration, needing external motivation like paying the rent at the end of the month, simple boredom and basic laziness.

His conclusion was that the writer “unconsciously tries to solve his [sic] inner problems via the sublimatory medium of writing”. In other words, a writer is blocked because of a deeper psychological issue he or she is attempting to work through by the act of writing.

This might have sounded enlightening at the time but 70 years on Bergler’s sweeping theory seems, at best, a bit woolly. Could every incidence of writers struggling to put words on the paper really be explained by exploring their relationships with their mothers? Hmm.

Perhaps the earliest recorded example of writer’s block afflicted Samuel Taylor Coleridge. He’d produced almost all his best work by his mid-twenties and genuinely seemed to struggle after that. By 1804 he was 32, in poor health and taking increasing amounts of opium. A note in his journal reads, “So completely has a whole year passed, with scarcely the fruits of a month. O Sorrow and Shame – I have done nothing!”

Now, by then he had already come up with The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan and collaborated with Wordsworth on the Lyrical Ballads so it’s fair to say he’d assured his place in the English literary canon.

That would have been scant consolation every time he sat at his desk, dipped his pen in the inkpot, dangled it over a blank sheet of paper and found nothing arriving. When writing is effectively what defines you, losing the capacity to write is a terrifying prospect.

If writer’s block does exist, fear is one plausible explanation even for successful writers. Producing brilliant work and massive sales can throw up as many problems as rewards because you’re expected to at least emulate if not surpass your best with every subsequent literary effort. When you’ve enjoyed huge success, particularly with your first book, the prospect of replicating that level of success can be cripplingly daunting.

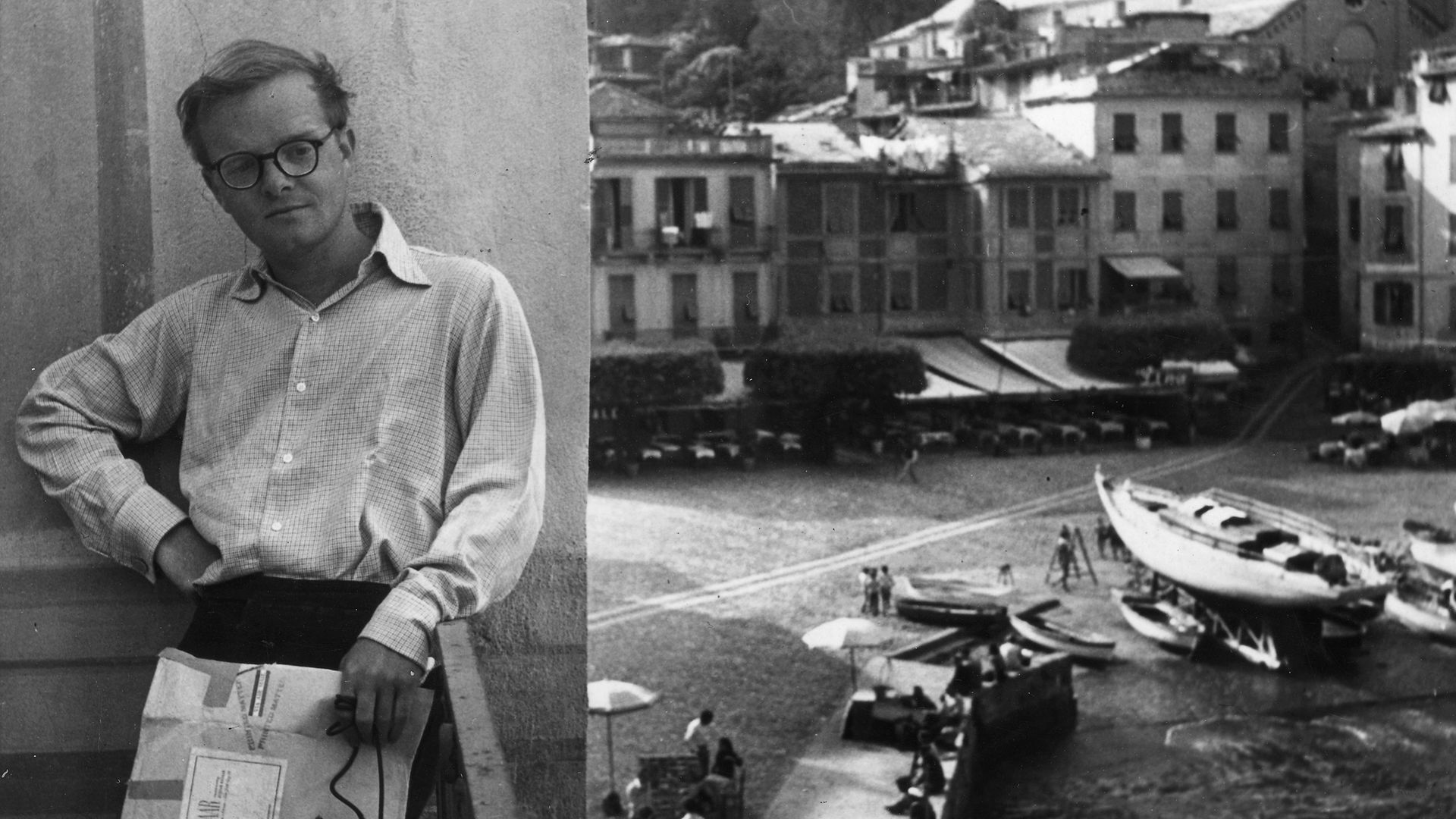

During her lifetime Harper Lee never published anything after her debut To Kill a Mockingbird became an international bestseller. Her close friend Truman Capote spent the last decade of his life talking about the searing satire on US high society he was working on, his finest work, he suggested, a book that never appeared other than a version cobbled together after his death that seemed no more than a reworking of some magazine articles.

In Cold Blood, a work that changed the entire face of narrative non-fiction, was another tough act to follow even for a writer as outwardly self-assured as Capote. In the words of Martin Amis, he “spent the last 10 years of his life pretending to write a novel that was never there”.

Fear can be a powerful force for a writer. It can inspire some and intimidate others. It can inspire and intimidate the same author at different points in their career or even just on different days. “It’s the fear you cannot do what you’ve announced to someone else you can do, or else the fear that it isn’t worth doing,” is how Tom Wolfe put it.

Perhaps writer’s block is the ultimate manifestation of that fear, an underlying dread that all writers are dealing with at some conscious or unconscious level. A mental portcullis clangs shut and the cursor stays flashing stubbornly at the top left-hand corner of the screen because perhaps sometimes the least scary option for a writer is not to write anything at all.

Many scribblers develop rituals and quirks in attempt to combat this fear, sometimes verging on superstition. Whenever a group of writers is gathered in one place it isn’t too long before talk turns to the particular pencil they have to write with or a specific desk in the British Library where they have to sit, little rituals and affectations without which they say they couldn’t produce a word.

Dan Brown has a pair of gravity boots from which he hangs upside down when he’s not feeling inspired. Philip Pullman can only write with a ballpoint pen on lined A4 pads with two punched holes. Virginia Woolf and Lewis Carroll wrote standing up, while Mark Twain, Marcel Proust and Capote could only write lying down. Gustave Flaubert was a sitter, writing to Guy de Maupassant that “one cannot think and write except when seated”, while Wordsworth composed much of his verse on foot, even if it meant doing countless circuits of his garden. All of them keeping the fear at bay.

I’ve always felt immune to this kind of thing. Any old pen, any old pad, any old keyboard, it doesn’t matter to me, I’ll still bash out any old nonsense. It was only when reading about other writers’ struggles during the pandemic that I realised my fear was as bad as anyone else’s, just expressed in a different, more retrospective way.

I never read reviews of my own books, good, bad or indifferent, for example, but perhaps more extreme – and possibly properly weird – I don’t keep copies of my own books either. When a book is published the author is sent a small number of free copies and mine are all given away as soon as possible.

When people ask me about it, I joke that I don’t need one as I kinda know what happens. I’ve also tried to convince myself it’s because I don’t write books for myself, I write them for other people to read so what’s the point in me sitting on them. More realistically, maybe I need to remove all the baggage of the old book before starting a new one and the fear is not for the next book being up to scratch, but the last one.

The pandemic has changed that though. If fear keeps writers from writing in the form of a psychological barrier, when you add the constant, thrumming anxiety of a colossal global crisis then it’s no wonder pages are remaining blank and books aren’t being written. I thought I was exempt but this last year has been the first time I haven’t had a book on the go in nearly two decades.

It doesn’t help when you think about those writers who sail blindly on, unaffected by anything as wishy-washy as crippling self-doubt and outright terror. Anthony Trollope, for example, wrote every day for three hours between 5.30am and 8.30am, knocking out 250 words every 15 minutes timed by his pocket watch. If he finished one novel, he would start another immediately and keep going until 8.30, when he’d go off to his day job.

Granted, this method produced 49 novels in 35 years, but think of all the Kit Kats he could have had.

What do you think? Have your say on this and more by emailing letters@theneweuropean.co.uk

FIVE GREAT BOOKS OUT THIS WEEK

BRIGHT BURNING THINGS

Lisa Harding (Bloomsbury, £11.99)

Once a highly-rated actor on the London stage, Sonya’s descent into alcoholism is clashing with her responsibilities as a parent to Tommy. A whirl of love, fear and drink, this is a book that complements Booker Prize winner Shuggie Bain. “Where parenthood is at once your jail and your salvation, it is almost claustrophobic – but in the most glorious way” said Three Women author Lisa Taddeo.

UNDER THE BLUE

Oana Aristide (Serpent’s Tail, £14.99)

A reclusive artist is forced to abandon his home and follow two young sisters across a post-pandemic Europe in search of a safe place, wondering if this the end of the world. Two computer scientists have been educating their baby, an AI program designed to predict what’s next for the human race, in a remote location. A gripping debut from this Transylvanian-born writer.

A SMALL REVOLUTION IN GERMANY

Philip Hensher (Fourth Estate, £9.99)

In 1981 Spike is 16 years old and full of the kind of adolescent vim that makes him keen to change the world, painting slogans on walls and making plans and manifestos for a better future. What happens if that mindset never changes? What happens if everyone else’s does? A thoughtful, engaging exploration on the legacy of youthful idealism, new in paperback.

THE COMPLETE TWO PINTS

Roddy Doyle (Vintage, £10.99)

A decade’s worth of bar stool back-and-forth between Doyle’s two lads in a Dublin pub shooting the breeze about current affairs, life and philosophy. Nuance, wit and personality combine in these pithy two-handers that showcase the author’s comic talents at their very best.

A SIMPLE PASSION

Annie Ernaux, trans. Tanya Leslie (Fitzcarraldo Editions, £8.99)

“A work of lyrical precision and diamond-hard clarity,” was the New Yorker’s verdict on this new edition of Ernaux’s slim yet incisive examination of a woman’s two-year relationship with a married man, the latest in Fitzcarraldo’s excellent series of new editions from one of France’s greatest contemporary writers.