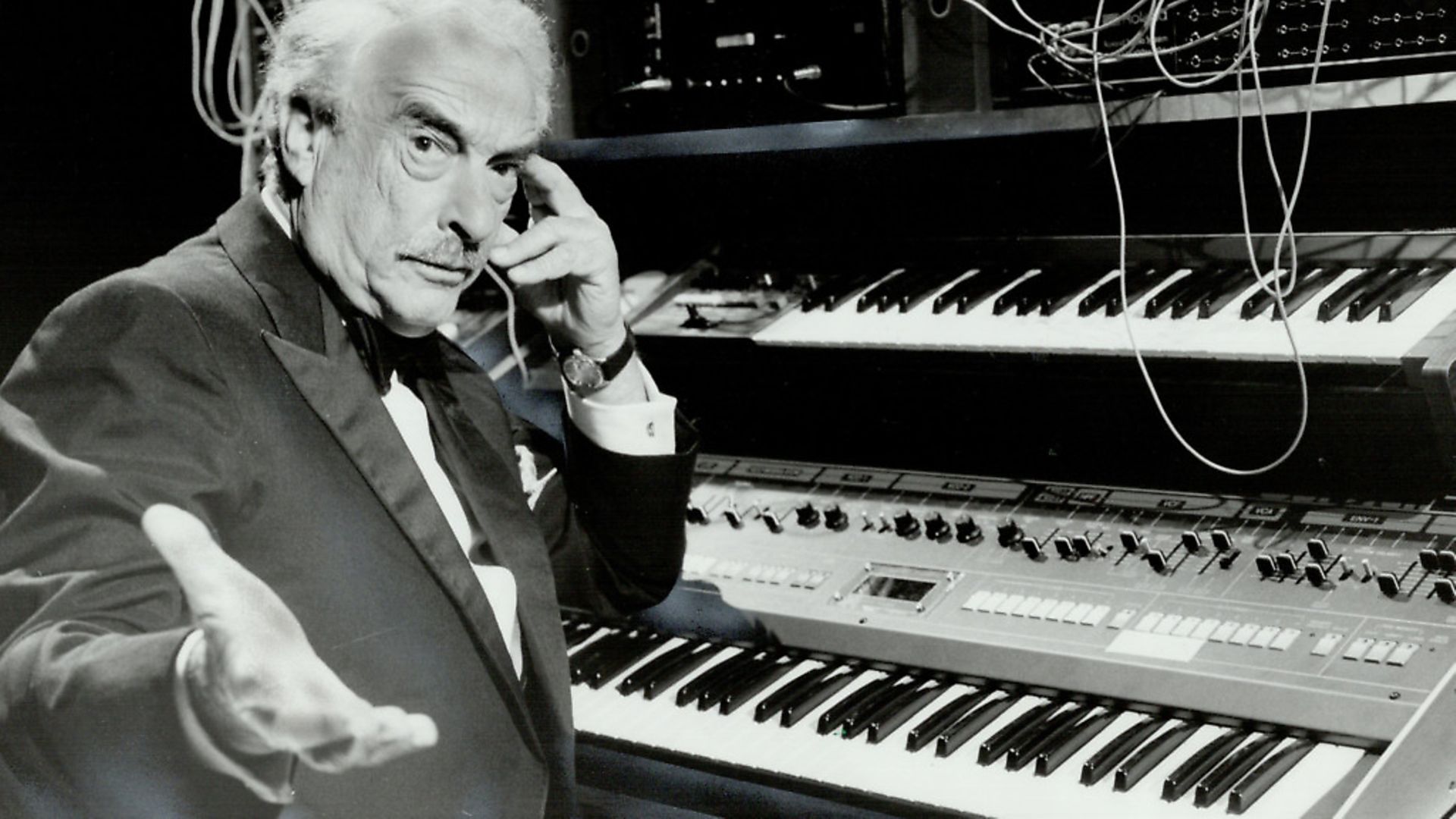

CHARLIE CONNELLY profiles the great Dane Victor Borge.

During the last year of the 20th century Victor Borge played 60 concerts. He was 90 years old. His material, a mixture of deft musical sketches and parodies interspersed with drily humorous quips and monologues, hadn’t changed much since he first began performing it in his native Denmark during the 1930s but it had served him well enough to become one of the world’s favourite entertainers and, for a while during the 1960s, its wealthiest.

“How many times does an orchestra play Beethoven’s Ninth, Fifth or Sixth, but people go back to hear it year in, year out,” he’d say in response to questions about the longevity of his routines. “I’m like apple pie. Generations come and go, they like it, they understand it. It doesn’t have to change with the times.”

It’s an old maxim that it takes immense talent to perform deliberately badly for comic effect. Tommy Cooper could do it; Les Dawson did it at the piano. Victor Borge was a master at it, a wildly gifted musician who could have made a career as a classical pianist but chose instead a different path, one of self-parody that made him one of the world’s favourite entertainers.

The clowning came as a response to nerves and manifested itself at an early age. The son of a Russian emigré violinist in the Royal Danish Orchestra and a pianist mother, the then Børge Rosenbaum began playing the piano at three and was soon feted as a prodigy paraded in front of the great and good of the Copenhagen cultural scene. He gave his first public concert at 13 but even by then was already a veteran of the Danish classical circuit.

“I was taken around and expected to play after dinner on pianos that were generally out of tune. Highly polished, but out of tune,” he recalled. “This poor kid would have to play Mendelssohn or Schubert on these horrors so I would talk as well to distract from the terrible sound of the instrument. I would make up a composer’s name or play pieces I just made up and my father would get angry with me because sometimes there were important people there.”

His antics didn’t prevent him gaining a scholarship to the Copenhagen Conservatoire before going on to study in Berlin and Vienna under some of the finest piano teachers in Europe. Such high stakes only increased the pressure on the young man, however, an experience that helped to drive him from the concert platform onto the nightclub stage.

“It was frightening,” he said of the experience many years later. “Even today when I play with the orchestra there are moments when I begin to shake. The problem everyone has, be they great or not so great, is that every time you perform you are defending yourself, proving that you are doing it well. You are auditioning every time you touch the piano because you never know who is in the audience. The nerves and the fear can take everything out of you and it just isn’t worth it.”

He began working the comedy circuit in his early 20s, developing the act that would become familiar to millions for the rest of the century, carefully learning his craft until his performances were honed to perfection.

“There has to be enough musical content to please the sophisticated and enough broad humour to satisfy those who have come just to laugh,” he said.

Comedy’s gain was music’s loss. The conductor Henri Temianka once said: “There is more to Borge’s piano playing than he allows us to hear, but in those fleeting moments we recognise an elegance of touch, a limpidity, a grace, a transparency, a talent that sets apart the few from the many.”

He married Elsie Chilton, an American, in Copenhagen on Christmas Eve 1933 and as the decade progressed developed popular routines that mocked Hitler and the Nazis, growing ever more threatening just over the border. When Denmark signed a non-aggression pact with Germany in 1939 Borge commented wryly, “now the Germans can sleep soundly in their beds knowing they are safe from Danish aggression”.

He would later describe a regular sketch he employed in which a man dressed as Hitler would walk onto the stage as he played and without looking up or missing a note Borge would pull out a pistol and shoot him dead, prompting a wild ovation every night. When the German consul complained to the Danish authorities, the next night Borge deliberately, hammily shot and missed, allowing ‘Hitler’ to march off in triumph to a volley of boos and catcalls.

When Germany invaded Denmark in the spring of 1940 Borge was fortunate to be touring in Sweden and couldn’t return home (he would later half-joke that he was top of Hitler’s list of Danes set for extermination). When, a few weeks, later the US president Franklin D. Roosevelt sent the ship American Legion to Petsamo, Finland, to evacuate the displaced Crown Princess Martha of Norway, Borge’s American wife was able to secure berths aboard for herself and her husband. The ship sailed for New York on August 16, the last neutral vessel to leave the region for the duration of the war.

Although he’d picked up a smattering of English from his wife, Borge would spend his early days in the US holed up in the cinemas of 42nd Street watching and rewatching films, repeating the dialogue to himself until he could converse freely and fluently. At around this time Børge Rosenbaum became Victor Borge and secured himself a gig at a nightclub which in turn earned him a place on Bing Crosby’s syndicated radio show Kraft Music Hall that ran for 56 weeks. From being unable to secure a job at a petrol station because of his poor English, Victor Borge found himself broadcasting to 30 million people every week instead.

Learning English later in life – he already spoke fluent French and Swedish – lent Borge a linguistic playfulness that provided some of his best material. There was the story he would tell of his grandfather who invented a drink called 3-Up, improved it to 4-Up and 5-Up, marketed it as 6-Up – and then died of a broken heart when it wasn’t a success. Even in his 80s he would inform audiences that he was a child prodigy “until three months ago”.

After the war he began broadcasting the weekly Victor Borge Show on NBC, but after the failure of his marriage to Elsie in the early 1950s found himself having to support an ex-wife and their two adopted children, a new wife, a stepdaughter and a son. These financial responsibilities led him to look beyond the radio studio and take his one-man show Comedy in Music on tour. By 1953 these shows had become so successful he was able to undertake a Broadway residency that ran for 849 performances, a record for a one-man show, and lasted for two-and-a-half years. By 1960 he had become the world’s highest-paid entertainer.

He would remain based in the US for the rest of his life, saying that he left Copenhagen in 1940 because, “while the world grew smaller and smaller, hatred grew bigger”. He kept an estate in Denmark, however, at which he would spend most of his summers. So impressive was his chateau, which boasted an orchard of 16,000 trees, the Danish government once asked if it might be loaned to accommodate the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev during a state visit.

“Mr Khrushchev can have the house for two weeks if he gives up Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia and East Germany,” he replied. “Otherwise it’s not available as I have already made my plans for the summer.”

This distaste for authoritarianism that stemmed from his escape from Europe in 1940 never left him. During the 1990s Borge gave a three-hour videotaped statement of his flight from the Holocaust to the Shoah Foundation and in 1963 became a founder and patron of Thanks to Scandinavia, a charity funding US education scholarships for Scandinavian students set up in recognition of the region’s efforts to assist victims of Nazi persecution.

It was an attitude that underpinned his humour. “A civilised delight of uncommon wit,” the Times called him, while one US critic said, “his humour is love, tolerance and understanding translated into laughter”.

“Humour is something that thrives between man’s aspirations and his limitations,” said Borge. “There is more logic in humour than anything else. We need more humour. Humour is warmth. Humour is music.”