The rising popularity of translated fiction shows we remain a country keen to look and learn beyond our shores, says Charlie Connelly.

I bring a glimmer of hope. It is just a glimmer, a small one, and perhaps one in the manner of the email I received from a cross-channel ferry company last week announcing it could offer me ‘peace of mind’ regarding travel after Brexit. This turned out to be a promise that if and when everything goes nuts after we leave the European Union and Kent becomes a giant lorry park I wouldn’t be charged for cancelling any crossings as a result, at least not for a limited period. As you can imagine, this fair cheered me up and suddenly Brexit doesn’t seem so bad after all. Ah, that peace of mind, you can’t put a price on it, you know.

Anyway the glimmer of hope I’m offering is a cultural rather than political or travel-related one. With Brexit giving such a loud and braying voice to the kind of nitwits who spend their waking hours typing ‘For God’s sake let’s just leave now’ under online news stories – whether they’re about Brexit or not – and whose patriotism is so sturdy they’re threatened by hearing Polish spoken on a bus, I feared that our national cultural discourse might grow ever more parochial.

Britain has produced more than its fair share of great music, art and literature over many centuries but much of it has been influenced by trends in and interactions with other parts of the world, especially Europe. From Boccaccio’s Decameron inspiring Geoffrey Chaucer to embark upon The Canterbury Tales to the influence of European dance music on our homegrown artistes today, British art and culture has always absorbed influences from outside these islands. Would Brexit change that, I wondered?

The answer in literary terms appears to be a resounding ‘no’, at least if recent figures commissioned by the Man Booker International prize from Nielsen Book Scan, the organisation that collates and analyses book sales in the United Kingdom, are anything to go by.

In 2018 overall sales of translated fiction in the UK went up by 5.5% as more than 2.6 million books were shifted. Not only were these sales worth £20.7 million to the publishing industry, they were also the highest recorded since Nielsen began tracking sales way back in 2001 (during which time sales of translated fiction have increased by a whopping 96%).

During the same period literary fiction written in English, while holding steady enough to be termed very healthy, plateaued.

So, while the prevailing rhetoric dictates that the ‘will of the people’ is apparently for Britain to withdraw into itself and turn the English Channel into a moat, more and more people are seeking out fiction from other countries and cultures written originally in an entirely different language.

‘Reading fiction is one of the best ways we have of putting ourselves in other people’s shoes,’ said Man Booker International Prize administrator Fiammetta Rocco when the figures were announced. ‘The rise in sales of translated fiction shows how hungry British readers are for terrific writing from other countries.’

These aren’t obscure, impenetrably symbolist tomes from earnest, frowning men in turtlenecks either: the likes of Elena Ferrante and Jo Nesbo lead the way, while books such as Michael Hofmann’s translation of Alone In Berlin by Hans Fallada and The Hundred-Year Old Man Who Climbed Out Of The Window And Disappeared, written by Jonas Jonasson and translated by Roy Bradbury, have been huge and unexpected bestsellers in Britain and across the English-speaking world.

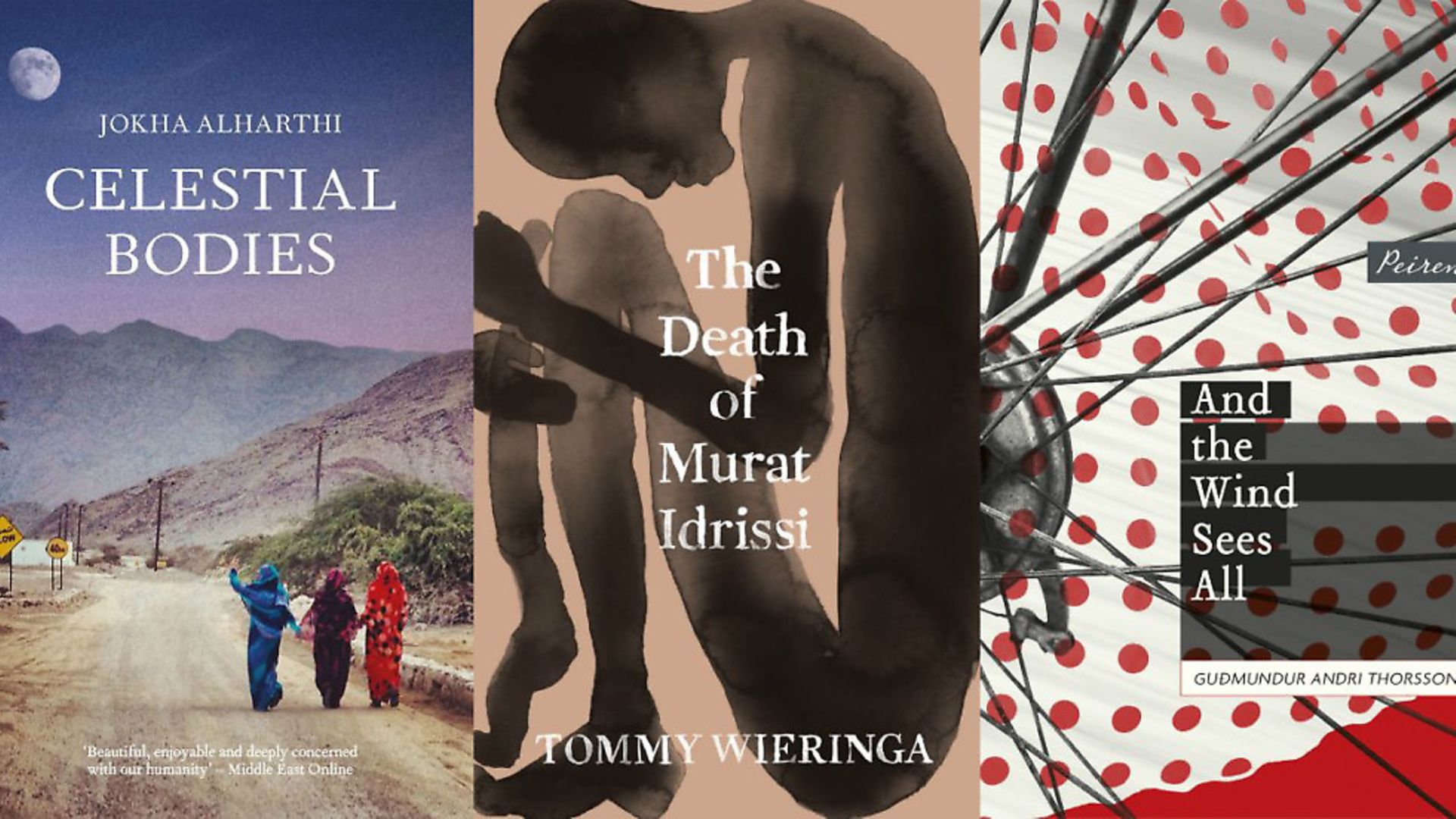

It’s not just about big hitters, though. Smaller presses like Peirene Press, Pushkin Press, Istros Books and Maclehose Press have been producing some wonderful works of translated fiction for many years now, much of it from Europe.

They’ve built loyal and growing followings thanks to high quality books and translations in beautifully-produced editions that are marketed imaginatively despite not having anything like the budgets of a major publishing house (Peirene offer an excellent value subscription schemes, for example, and on International Women’s Day earlier this month made all their titles by women – which is most of their output – half price).

Fitzcarraldo Editions meanwhile have enjoyed great success with their challenging list of translated fiction in plain blue or white covers that make their books instantly recognisable, especially since their Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Jennifer Croft, won the Man International Booker last year.

These presses and those like them deserve huge credit for opening up a whole world of literature to English-language readers. It’s a risky business: first you have to pick the right novel, then match it to the right translator. Then there’s the question of design – Peirene and Fitzcarraldo are among those whose covers are instantly recognisable and have justifiably earned reputations for high quality productions. Thankfully sales figures show these risks are proving more than worthwhile.

Whenever literary translators gather together they are soon comparing notes and collective eyerolls on the adjectives used about their contribution that crop up most often in reviews: faithful, lively, agile and vibrant are the most common.

They do deserve more than that, it’s true, but outside academia there aren’t many reviewers with the linguistic chops to pronounce with much authority on the quality of the translation. This shouldn’t detract in any way from the immense contribution of the translator to a successful novel, however. It’s not enough to have a good grasp of a language and a hefty dictionary on your shelf, the best translators are also outstanding writers, people with an ear for and sensitivity to the nuance, rhythm and atmosphere of the original.

The best translations make you forget you’re not reading the author in their original language (and many of them can currently be found on the Twitter page of Charlotte Collins, co-chair of the Society of Authors Translators’ Association, at @cctranslates where she is tweeting one great literary translation per week for 60 weeks to mark the association’s 60th birthday).

Nowhere is the translator’s contribution credited more deservedly than by the Man Booker International Prize, whose £50,000 cash pot is shared equally between the author and their translator.

This year’s longlist, the last Booker under the Man sponsorship, was announced last week: an outstanding selection that demonstrates perfectly the current strength of translated fiction we’re seeing reflected in sales. For me the international prize is always more interesting than the main Booker because of the sheer global reach of the selections and the variety of styles and subjects they encompass and this year the variety is as strong as the quality.

The 13 books from 12 countries see Europe strongly represented, not to mention nearly two-thirds of the selected books being written by women and only two titles coming from large publishing conglomerates. Last year’s winner Olga Tokarczuk makes the cut again, following Flights with Fitzcarraldo’s excellent production of her Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.

Like Flights, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead is an unconventional yet immensely absorbing novel set in a village in southern Poland where an elderly woman describes events surrounding the disappearance of her dogs, after which members of the local hunting club start turning up dead.

Part thriller, part meditation on injustice, mental health and spirituality, the judges called Tokarczuk’s novel ‘an idiosyncratic and bleakly humorous indictment of humanity’s casual corruption of the natural world’.

Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead has an excellent chance of scooping a second successive gong for its author, albeit with a different translator from Flights, while for me other strong contenders include Four Soldiers by Hubert Mingarelli, written in French, translated by Sam Taylor and published by Portobello Books. It is set largely during the winter of 1919 when four friends are fighting in the Russian Civil War camp in a forest on the Romanian front. Gathering around a pond to smoke and wait for their unit to be moved on, the friends ruminate on friendship, nature and war in a manner that reminds me slightly of the Finnish national epic Unknown Soldiers by Vaino Linna (albeit at a fraction of the length).

Deborah Bragan-Turner’s translation of The Faculty of Dreams by Sara Stridsberg from MacLehose Press, meanwhile, sees the author revisiting the life of American radical feminist Valerie Solanas, most notable for her SCUM Manifesto and 1968 attempt on the life of Andy Warhol. Revisiting the sites associated with Solanas, including the courtroom where she was tried for the attempted murder and the San Francisco hotel room where she died aged 52 in 1988, Stridsberg constructs imaginary conversations and memories to bring this enigmatic and fascinating figure to life.

The judges called Stridsberg’s heartbreaking book, ‘an acute exploration of the imminent possibility of tragedy in all our lives – performative, exhilarating, searing’. While I wouldn’t necessarily advise putting money on any of these – I am, after all, the person who declared Frank Lampard a ‘one-season wonder’ back in 2003 – I think they are particularly outstanding books from a strong list whose 13 titles will be whittled down to six on April 9 with the winner announced on May 21.

Appropriately, there came news in the same week the longlist was announced that one of the oldest translations in the literary history of these islands had turned up. A couple of fragments of a 15th century Irish language version of an influential 11th century Persian medical encyclopaedia called The Canon Of Medicine by Ibn Sina, were unearthed in the domestic library of a big house in Cornwall.

‘This is an example of learning in its purest form, it transcends all boundaries, it transcends cultures and religions, it unites us all in a way that other things divide us,’ said Pádraig Ó Macháin from University College, Cork, who helped authenticate the vellum fragments discovered in the binding of a book from the 16th century.

‘That’s personally important to me because I think learning is without borders and that this is maybe an opportunity to express that and make people understand it.’

It’s this combination of historic and contemporary literary translations being celebrated in the same week that reassures me our cultural perspective, despite everything, will remain outward-looking whatever Brexit might bring.

It’s in our genes, that glimmer, and it’s stronger than you might think.