Why there was more to the revolution than simply persecution and bloodshed.

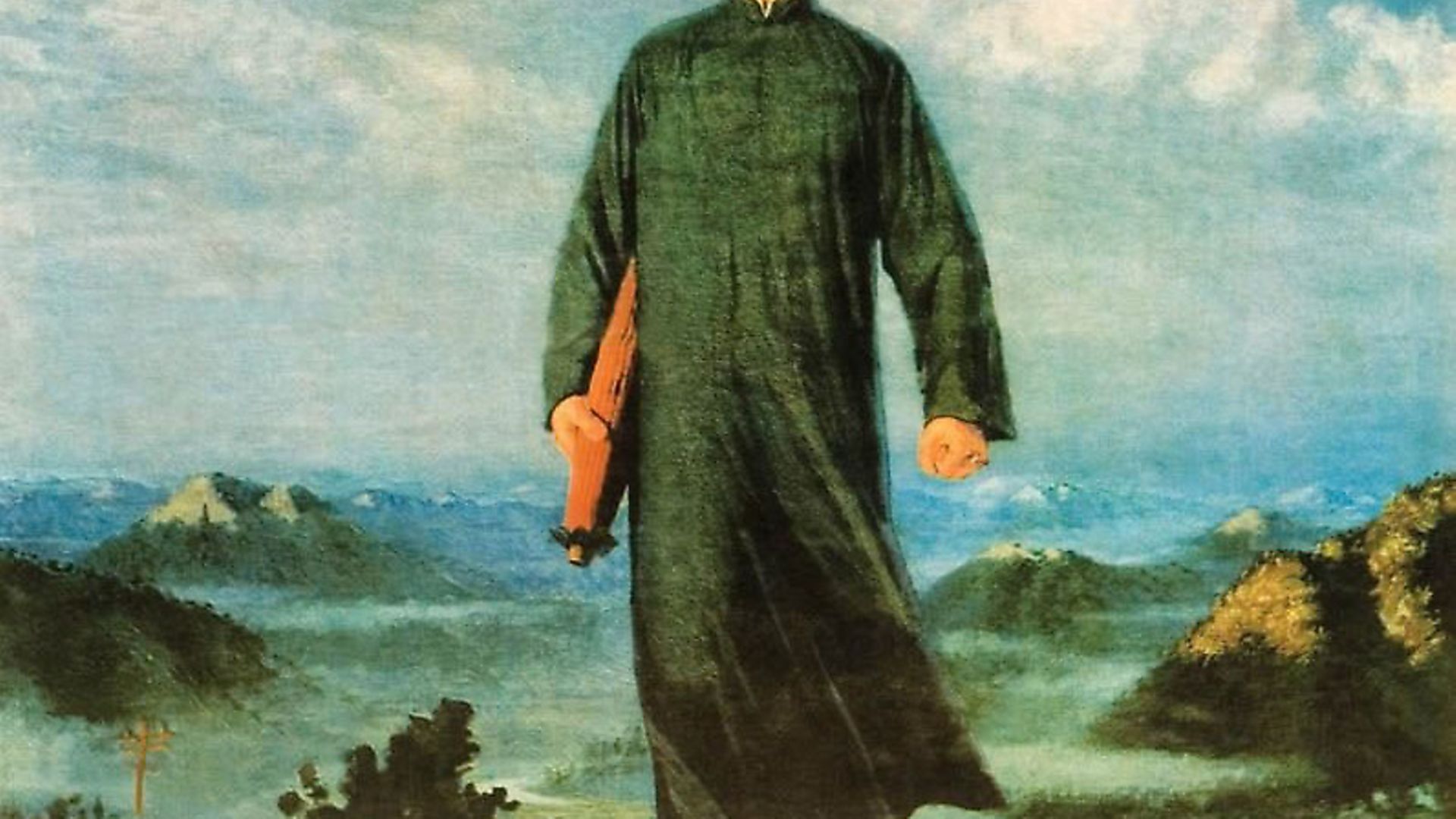

A young man strides out of mountainous countryside, a priestly figure wearing robes ruffled by the wind, with a red scroll beneath one arm and the other hand clenched into a fist.

It is a benign image – and a travesty of the reality. The visionary figure is a 24-year-old Mao Zedong but the portrait was painted when the Chinese dictator was in his seventies. By then he had overseen the deaths of up to 45 million people between 1958 and 1962 in the disastrous Great Leap Forward, which imposed industrial and agricultural reform on the population with a ferocious and deadly zeal.

Entitled Mao Zedong Goes To Anyuan the painting became one of the most popular representations of the Great Helmsman and is among the most telling images in Cultural Revolution, an exhibition of posters glorifying Mao at the William Morris museum in Walthamstow, London.

A museum housing the wallpaper and furniture designs of the great Victorian might seem an incongruous venue for such strident agitprop but Morris, who lived in the building from 1848 to 1856, was himself a Marxist. He created a utopian world in his 1890 fantasy novel News from Nowhere in which there was no private property, no authority, no money and class was eradicated. Sexual angst was a thing of the past because everyone would be happy.

But Morris sought change by teaching and argument, and although Mao preached about ‘letting a hundred flowers blossom, a hundred schools of thought contend’ and insisted it was revolutionary policy to ‘promote the progress of the arts and the sciences and a flourishing culture in our land’ what he really meant was that all art should serve the worker, the peasant and the soldier. And himself.

In 1966 his leadership was threatened by other elements in the Communist Party, who were shocked at the excesses of the Great Leap Forward, which had resulted in millions dying of famine. In a preemptive strike he resolved to destroy his rivals and any dissident thought in what he dubbed the Great Purge.

Mao’s first target was nothing less than the destruction of all Chinese artistic traditions, and the person he chose to carry out this Cultural Revolution was his wife, Jiang Qing, who he said ‘was as deadly poisonous as a scorpion’.

Vain, ambitious and ruthless, Mme Mao denounced all forms of films, opera and art, because, as she claimed, they were made by people opposed to her husband. She made it her task to ensure that the only work to flourish would be for propaganda purposes. Only one art form was permitted – the praise of Mao and his reforms. Writers and scholars were imprisoned, traditional artists who failed to create suitable revolutionary themes were denounced or imprisoned, and from the launch of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 until his death in 1976, all were compelled to toe the Party line.

One of the favoured artists was a government propagandist, Liu Chunhua, who painted Mao Zedong Goes To Anyuan. He belonged to the Red Guard – paramilitary units of radical youths – whose mission was to attack the ‘four olds’: customs, habits, culture, and thinking. It made him just the man to portray the young Mao in one of his much vaunted early successes organising the 1922 non-violent strike of 13,000 miners and railway workers in south eastern China.

Deemed by Jiang Qing to be a suitable model for revolutionary art, she had several hundred million copies printed, more than the population of China. Artists were considered elitist so were often compelled to disavow their work and share the credit with other collaborators and even the loyal Liu Chunhua had to share the credit for his work with ‘others’.

It is an unusual representation of the Chinese leader who is more often shown in his drab proletarian tunic as he is in Chairman Mao in Zhongnanhai, which portrays him a keen-eyed figure of wisdom, an amiable big brother, outside the Communist Party headquarters, next to the Forbidden City in Beijing.

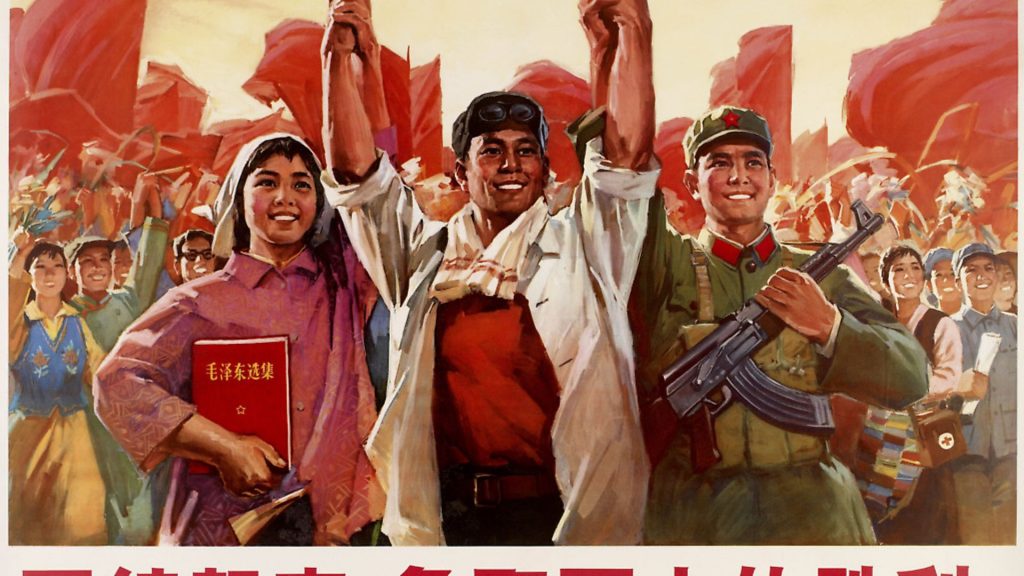

Jiang Qing insisted that the posters should be of the ‘reddest of reds’ – the colour of the revolution and the one to have the biggest impact with the illiterate masses – so framed in red, the inscription reads on the right ‘Long live the great Chinese Communist Party!’ and on the left ‘Long live our great leader Chairman Mao!’

As well as promoting this cult of personality, it was essential that the people were portrayed as happy, smiling and productive. In At the Happy Hearth of the Motherland a gathering of different ethnic groups from across the country crowd around Mao.

They are eager and questing, their self reliance – and the success of the revolution – proved by the abundance of produce they have with them, while the source of their inspiration appears, as ever, a beneficent force. Needless to say, his image had to be idealised – today we would use Photoshop – and it is quite likely that Mao himself was painted by a more skilled portraitist, just to ensure he is perceived as the first among equals.

The traditional landscape painting in the background is a mighty nine metres wide and is entitled This Land with so much Beauty Aglow after the opening line of one of Mao’s poems. Today it hangs in the Great Hall of the People on Tiananmen Square.

Similarly, Ambition in the Countryside reflects Mao’s edict that the educated youth from Chinese cities were to go ‘up to the mountains and down to the countryside’ to learn from peasants in the remote corners of the nation. Here dewy-eyed youngsters meet an avuncular Mao, proudly clutching farming implements and sacks bulging with seeds.

Another group reflects Jiang Qing’s own enthusiasm for dance and opera – like many senior communists she hankered after the glamour and sophistication of the West – and in Long Live the Triumph of Chairman Mao’s Revolutionary Line for Literature and Art!, designed by Ding Jiasheng, a professor in the stage design department at Shanghai Theatre Academy (and others), characters from the model dramas which she promoted were performed to the exclusion of almost all other entertainment.

Their preposterously stiff poses and rictus smiles, not to mention the revolutionary garb, all served to hide the horrible reality in the same way that party newspapers depicted the revolution as an epochal struggle to inject new life into the socialist cause.

‘Like the red sun rising in the east, the unprecedented Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution is illuminating the land with its brilliant rays,’ proclaimed one editorial. It was the young, like the idealists portrayed here, who were mobilised by Mao to bring about his revolution. He unleashed the people – his Red Guards – on the party, and anyone thought to be undermining the communist cause, and urged them to purify its ranks.

His Little Red Book had to be carried and brandished at all public meetings, the young were ordered to betray teachers and sow seeds of hate which swiftly grew. Schools and universities were closed and churches, shrines, libraries, shops and private homes ransacked or destroyed as part of a remorseless assault on ‘feudal’ traditions.

Blood flowed as Mao ordered security forces not to interfere in the Red Guards’ work, which resulted in nearly 1,800 people losing their lives in Beijing in August and September 1966 alone.

This militancy is reflected in Unite for Greater Victory! and Workers of The World, Unite! The message is clear – and emphasised in red; the revolution is in the grasp of the people.

In Unite for Greater Victory three figures stand hand-in-hand. One represents the archetypal peasant woman grasping Mao’s collected works, a steel worker whose endeavour will help drive China into modern industrial times and a soldier with his gun. Workers of The World, Unite! uses the words from Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto of 1848 with images of ardent, multi-racial youth lustily singing revolutionary songs.

The people had to be reassured they were protected by the Red Army. China was preparing for an attack from the USSR during a border conflict in March 1969 and Mao put the country on alert for a nuclear onslaught, ordering that everyone should ‘deeply dig caves, extensively store rice, and never seek hegemony’.

Wait in the Preparation for the Enemy, Annihilate all Intruders has the reassuring image of a heavily armed force led by a soldier waving a red flag, the men poised, guns and bayonets at the ready for attack. In the background smoke from the factories testify to the revolution’s industrial power.

Judging by the credits attached to the poster – ‘Designed by the revolutionary committee of Lihua Paper Mill (Shanghai) and the revolutionary committee of Shanghai Shipyard and published by Shanghai People’s Publishing House and printed by Shanghai Shipyard’ – this is a typical example of the collaboration between artists’ groups, and the role of a committee which might well have reviewed the image and sent it back more than once to make sure everything was on message.

In a change of style, the exhibition – which is a travelling show organised by the University of Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum – demonstrates how the art of guohua – the traditional Chinese medium of brush and ink – was sometimes permitted, but only if the landscapes incorporated revolutionary elements such as men and women in military uniform, model workers and symbols of modern industrial achievement.

On the Banks of the Yangzi River does indeed have mountains and rivers – ‘How beautiful are the rivers and mountains!’ reads a caption, which is the opening line of another poem by Mao – but the picture is really a message to the world of China’s progress, with the Nanjing petro-chemical plant belching smoke over that beautiful scenery.

A similar approach is brought to New Aspects of Lake Tai – with its junks on the river and the forested hillsides – which is by the same artist, Song Wenzhi, who trained as a traditional landscape artist but obviously felt he had no option but to add pylons marching triumphantly over the hills and valleys.

Everything is geared to the propagation of the chairman as an invincible figure, even messages on matchboxes which, improbably, were decorated with admonitions to the people, such as to wash their hands before eating and after visiting the toilet, to grow more castor oil plants and not to drop orange peel on the street.

All this was part of the ruthless control that Mao exercised over the masses.

An estimated three million people died in the Cultural Revolution, maybe as many as 100 million suffered starvation, torture, death and execution throughout his 40 years as leader of the Communist Party and head of state, but with his death in 1976 the mass hysteria and the terror came to an end.

Jiang Qing, who used to boast ‘I was Chairman Mao’s dog. Whoever he asked me to bite, I bit’ was arrested in October 1976 by the new leader Hua Guofeng and was locked away in prison until she committed suicide in 1991.

Within three years of Mao’s death a dissident group of photographers, the April Photo Society, staged an exhibition in Beijing entitled Nature, Society and Man and thousands flocked to the Stars Art exhibition, organised by avant-garde painters and sculptors, which attacked Mao and Jiang Qing for their control over the arts.

A collection of the works were published in book form and included a dedication written by Hua Guofeng. It helped him win popular support. Like Mao, he was not a man to miss the chance of self-propaganda.

• Cultural Revolution runs at the William Morris museum until May 27