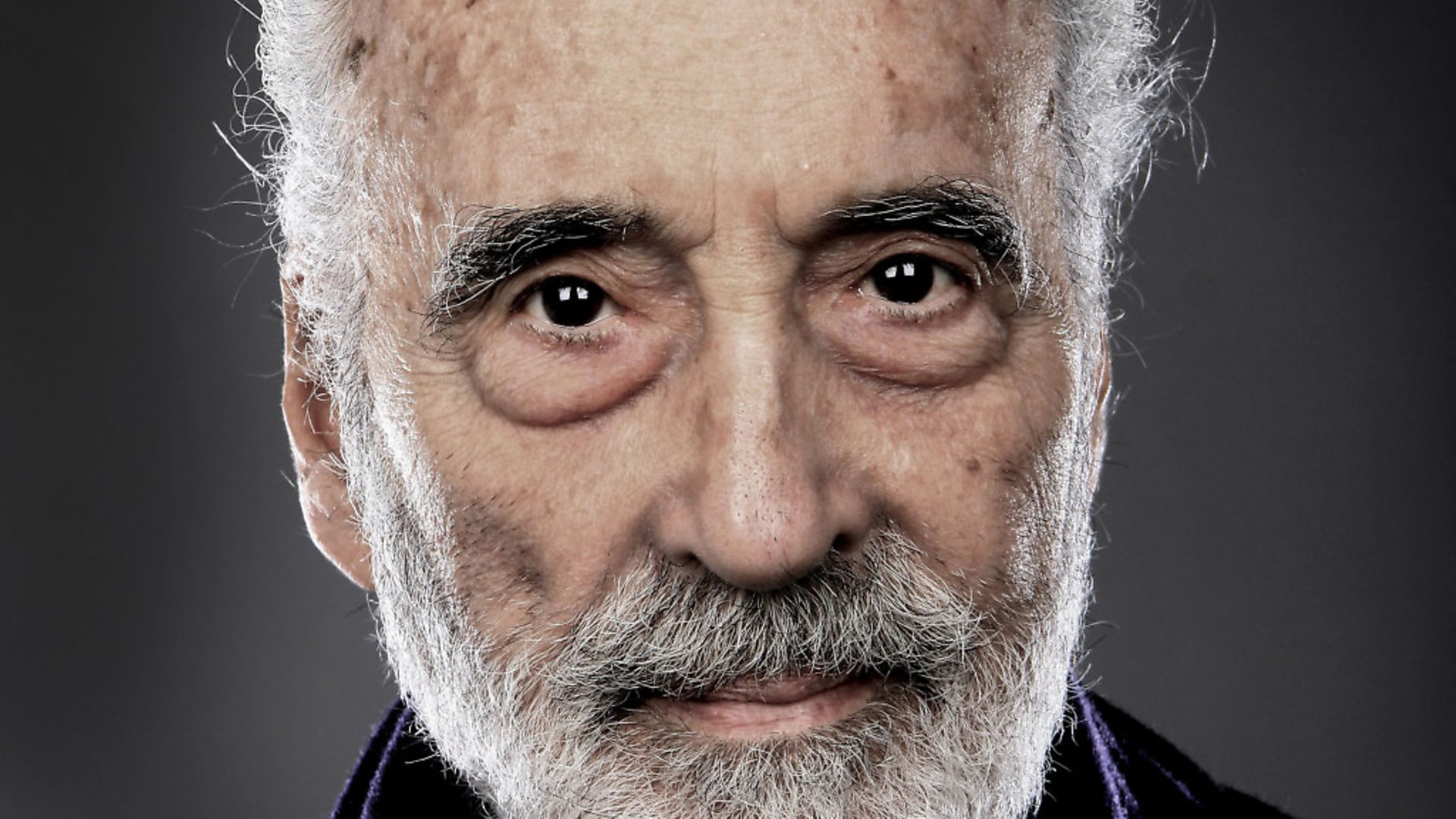

TIM WALKER looks into the life and career of Christopher Lee, best known for his portrayal Dracula.

There are certain parts – and Dracula is one of them – that require of the actor playing them some sense of being in on the joke with film-goers. Christopher Lee never saw anything funny about what was only ever a job to him. If anything horrified him, it was a giggling stranger coming up to his wife Gitte in the street and asking if she was ‘the bride of Dracula’.

He felt that insulted him every bit as much as her. I recall him telling me how he’d reminded this funster that he hadn’t played the Transylvanian blood-sucker in decades. An actor can move on – and, of course, Lee did with parts in the James Bond, Star Wars and Lord of the Rings franchises – but often the fans can’t, not least because in his case the old Hammer horrors are still a regular staple of late night television.

Lee’s occasional co-stars Peter Cushing and Vincent Price took the ribbing in good part, but that wasn’t for Lee. Maybe it was because they’d a come from a traditional stage background they had a more natural empathy with ordinary punters. Maybe, too, Lee’s wartime experiences attached to the SAS and SOE as an RAF liaison officer – when he’d often have to make decisions about whether people lived or died – had also left their mark.

Within the acting profession, Lee was often seen as stand-offish and remote. The easy-going Roger Moore was intrigued by him when they’d appeared together in The Man With the Golden Gun. Although Moore liked him, he admitted he couldn’t help but tease a man who was so deadly earnest. The crew on The Far Pavilions struggled not to guffaw when, in the middle of a scene, Rupert Everett’s horse had attempted to mount Lee’s, and, in the ensuing melee, first the wig Lee was wearing for the part came off and then his own wig, which no one was supposed to know about.

During the making of The Three Musketeers, Lee’s co-star Oliver Reed had secretly spiked his orange juice with vodka. A few glasses had rendered Lee insensible. He told Reed the next day that what he had done was unprofessional and refused to talk to him for some time. My guess is Reed was just trying to get him to loosen up a bit, but, when I got to know Lee around the turn of the millennium, I soon worked out that was never going to happen.

It was probably Lee’s sense of utter conviction in his all-too-often preposterous films that had made him a hero of mine as I was growing up. After I’d done an interview with him – when he’d joked I seemed to remember a lot more about his career than he did – he was happy to meet for a series of lunches at Le Caprice and his club, Buck’s. He was then in his eighties, but his work – or, more to the point, his income stream – mattered to him as much as ever.

Occasionally he’d admit to disappointments – if only he’d got the part of the old butler in The Remains of the Day and he regretted turning down the role Leslie Nielsen ended up making his own in the Airplane films – but, mostly, he had run his career with an almost infallible business acumen.

He could be almost chillingly detached about it, such as when his name began to appear before Cushing’s in the opening credits to their later films together. Lee said simply that he’d asked his agent to fix it for him as he felt he had become the better-known star. He added that Cushing’s wife Helen had registered her displeasure, but his old friend never mentioned it.

In the 1970s, when Cushing loyally kept appearing in increasingly ropey films for Hammer, Lee saw there was no use staying in Britain, where the industry was starting to go into sharp decline, and decamped to Los Angeles. It turned out to be a typically canny move and a part in Airport ’77 turned out to be the first in a remunerative series of blockbusters.

Lee eventually came back to Britain – residing in some style near Sloane Square in London – and a knighthood ensued. His fellow actors might not have been so sure he deserved it – Dame Eileen Atkins felt such honours ought to be the preserve of theatre luminaries – but Lee got to have the last laugh. He was still working when he died in 2015 at the age of 93 and had probably made more money than any actor of his generation. What no one could ever deny is that he was one of the great survivors.