Different from the others, German actor Conrad Veidt goes down in history as one of the most remarkable European lives. CHARLIE CONNELLY reports.

Dr Caligari was a showman in the old-fashioned mould. Drawing a crowd by ringing a handbell outside his fairground tent, he’d then sweep his arms high and wide, cape rising with them like wings, cane held like a sceptre, and have the gathering awestruck at the prospect of seeing his remarkable protégé just the other side of the canvas. Cesare, he cried, was a 23-year-old somnambulist who had slept night and day his whole life. But if the ladies and gentlemen would be so good to step inside, he, Dr Caligari, would rouse Cesare from his slumbers for their delight and delectation.

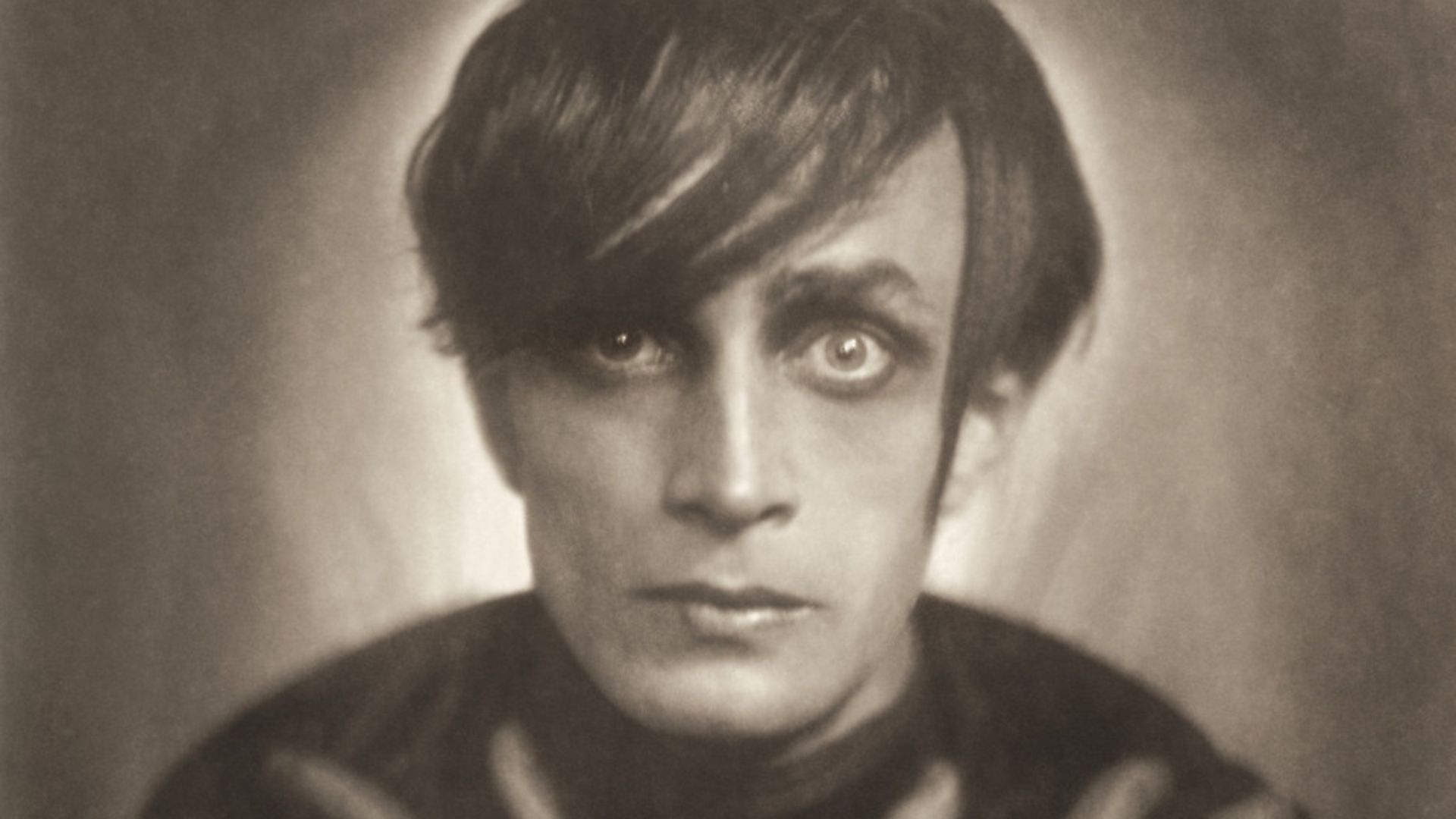

Once on the stage Caligari hoisted back a curtain to reveal a wooden cabinet resembling a roughly-hewn, upright coffin. Opening the doors the audience beheld a tall, gaunt figure, clad head to toe in skin-tight black sweater and trousers, a shock of black hair above a pan-stick white face, all cheekbones and thick eyebrows, deep in sleep but standing supported by the dimensions of the cabinet.

Caligari commanded him to wake. There was a furrowing of the brow, barely detectable at first, then a slight grimace. And slowly, very slowly, Cesare opened his eyes. The lids kept widening until, after what seemed like an age, he wore an expression of wide-eyed astonished bewilderment at the crowd he saw before him.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari was a landmark film when it appeared in Germany in 1920 and the relaxation of a ban on the international distribution of German pictures soon afterwards made the expressionist horror a worldwide hit. Cesare opening his eyes became one of cinema’s most famous moments. The film’s imaginative sets and a gripping script were memorable enough but it was the performances of the two leads that really made the film stand out; Werner Krauss as Caligari and Conrad Veidt as Cesare. So unsettling was Veidt’s performance in particular that when Caligari was first shown in Berlin in February 1920, just a month after filming had finished, women screamed when Cesare opened his eyes. Later in the film when Cesare abducts the female lead there were reports of women in the audience fainting with fear. The 27-year-old Conrad Veidt had arrived.

He always had a remarkable presence whatever the role, be it on screen, on stage, or off duty altogether. Born in Berlin he had early ambitions to be a surgeon, but an appearance in a school play changed the course of his life. He adored the applause, he said later, and craved more of it. Conscripted in 1915 and sent to the Eastern Front, Veidt participated in the Battle of Warsaw until a combination of jaundice and pneumonia saw him discharged on medical grounds, leaving him free to pursue an acting career. After befriending the doorman at Max Reinhardt’s Deutsches Theater in Berlin, Veidt wangled his way inside, auditioned for Reinhardt by reciting a chunk of Faust – the whole of which he had committed to memory – and was soon working his way up from small parts to leading roles. Indeed, so good a stage actor did he become that one critic pleaded, ‘I pray that this young man will never enter the films’.

Christopher Isherwood summed up Veidt’s charismatic presence when he saw him at an all-male costume ball at Magnus Hirshfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science in 1929.

‘The respectability of the ball was open to doubt, but it did have one dazzling guest: Conrad Veidt,’ Isherwood recalled. ‘The great film star sat apart at his own table, impeccable in evening tails. He watched the dancing benevolently through his monocle as he sipped champagne and smoked a cigarette in a long holder. He seemed a supernatural figure, the guardian god of these festivities, who was graciously manifesting himself to his devotees. A few favoured ones approached and talked to him but without presuming to sit down.’

Veidt’s presence at the ball was no surprise. He’d always embraced and exhibited the kind of tolerance that characterised the free-spirited cultural atmosphere of Weimar Germany in the 1920s. A year before his unforgettable performance as Cesare he had starred in the groundbreaking film Anders als die Andern (‘Different from the Others’), a production in which Hirschfeld had a significant creative role and one containing one of the first sympathetic portrayals of homosexuals ever seen on film. Veidt’s unabashed liberal values would come sharply into focus as darkness descended upon Germany during the 1930s.

The Cabinet of Dr Caligari established him as a gifted horror actor in particular, and the 1920s saw him turning in notable screen performances in German productions such as Orlacs Hände (‘The Hands of Orlac’) as well as portraying a range of real-life characters from Nelson to Paganini to Ivan the Terrible.

In the late-1920s he sailed for the US, scoring a notable hit in the 1928 Paul Leni silent The Man Who Laughs, a film adapted from a Victor Hugo novel. Veidt took the starring role of Gwynplaine, whose face was frozen in a permanent grin. Despite the rictus smile, he managed to turn in a performance of deep sensitivity that later struck a chord with the creative team at DC Comics, who used Veidt’s portrayal as the basis for the Joker.

Hopes of further roles in the US were dashed by the advent of sound: Veidt’s heavily accented English didn’t translate to the talkie era and he returned to Germany. Despite the disappointment he was excited by the advent of sound in cinema and displayed impressive foresight on the topic to the Berliner Tageblatt when he arrived home. The films with sound he’d seen, he said, were ‘too attached to the stage’.

‘We must write sound films, not sound film theatre pieces,’ he insisted. ‘What today is still a hybrid must become an independent art.’

In 1933 he married his third wife Ilana, who was Jewish, just as Joseph Goebbels began to focus his attention on the German entertainment industry. When film actors were presented with a ‘racial questionnaire’ to determine their suitability to continue working under the Third Reich, Veidt wrote that he was Jude, a Jew. He wasn’t, but as a man virulently opposed to anti-Semitism and married to a Jew he wanted to demonstrate his solidarity. As one of the nation’s best-known actors Goebbels was keen to keep Veidt on screen, telling him that if he divorced Ilana he could keep working. At that, the newlyweds packed up their belongings and went to England.

One of his first roles in his new home was the lead in the 1934 anti-Nazi film Jew Süss, his first English-speaking part. Six years later a German version would also appear, a hideously anti-Semitic interpretation in which Werner Krauss, who’d played Dr Caligari opposite Veidt and went on to become an enthusiastic Nazi, took several roles as grotesque Jewish stereotypes.

Not only did Veidt take out British citizenship in 1939, he donated his life savings to the British war effort. Keen to make as much of a contribution as possible, in 1941 he returned to California with a print of his film Contraband, hoping its distribution in the US might build support for America joining the war and ensuring the proceeds helped fund the fight against Nazism in Europe. While in Hollywood, his English now fluent, Veidt began accepting film roles as evil Nazi officers, most notably Major Heinrich Strasser in Casablanca.

‘This role epitomizes the cruelty, criminal instincts and murderous trickery of the typical Nazi,’ he said of the role. ‘I know this man well. He is a man who turned fanatic and betrayed his friends, his homeland, and himself in his lust to be somebody and to get something for nothing.’

Veidt still had much to do, both for the war effort and his career when he collapsed and died from a heart attack on a Hollywood golf course at the age of 50. It was a huge loss to the world of film, but at least in Cesare and Strasser in particular he had created two of the 20th centuries most memorable, indelible film villains. Even now, a century on, Cesare opening his eyes remains as unsettling a cinematic experience as it did to those Berlin women at the early screenings.

‘It intrigues me to think there is another man abroad in the world who resembles me,’ Veidt told an interviewer shortly before his death. ‘That I can sit in this hotel room with a scotch and soda talking of him and yet that shadow of me is out there somewhere, swaying audiences in a darkened theatre with impressions of love, or hate, or deceit.’